Originally published 25 January 1993

It is a common conceit among high-energy particle physicists to compare their giant accelerating machines to the Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages.

Robert Wilson, former director of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), draws these analogies: Cathedrals were intended to reach new ultimates of height, and accelerators push new limits of energy; the aesthetic appeal of both structures is based on the use of cutting-edge technologies; the builders of cathedrals and accelerators were daring innovators, fiercely competitive along national lines, yet basically internationalists.

Leon Lederman, Wilson’s successor at Fermilab, adds: “Both cathedrals and accelerators are built at great expense as a matter of faith. Both provide spiritual uplift, transcendence, and, prayerfully, revelation.”

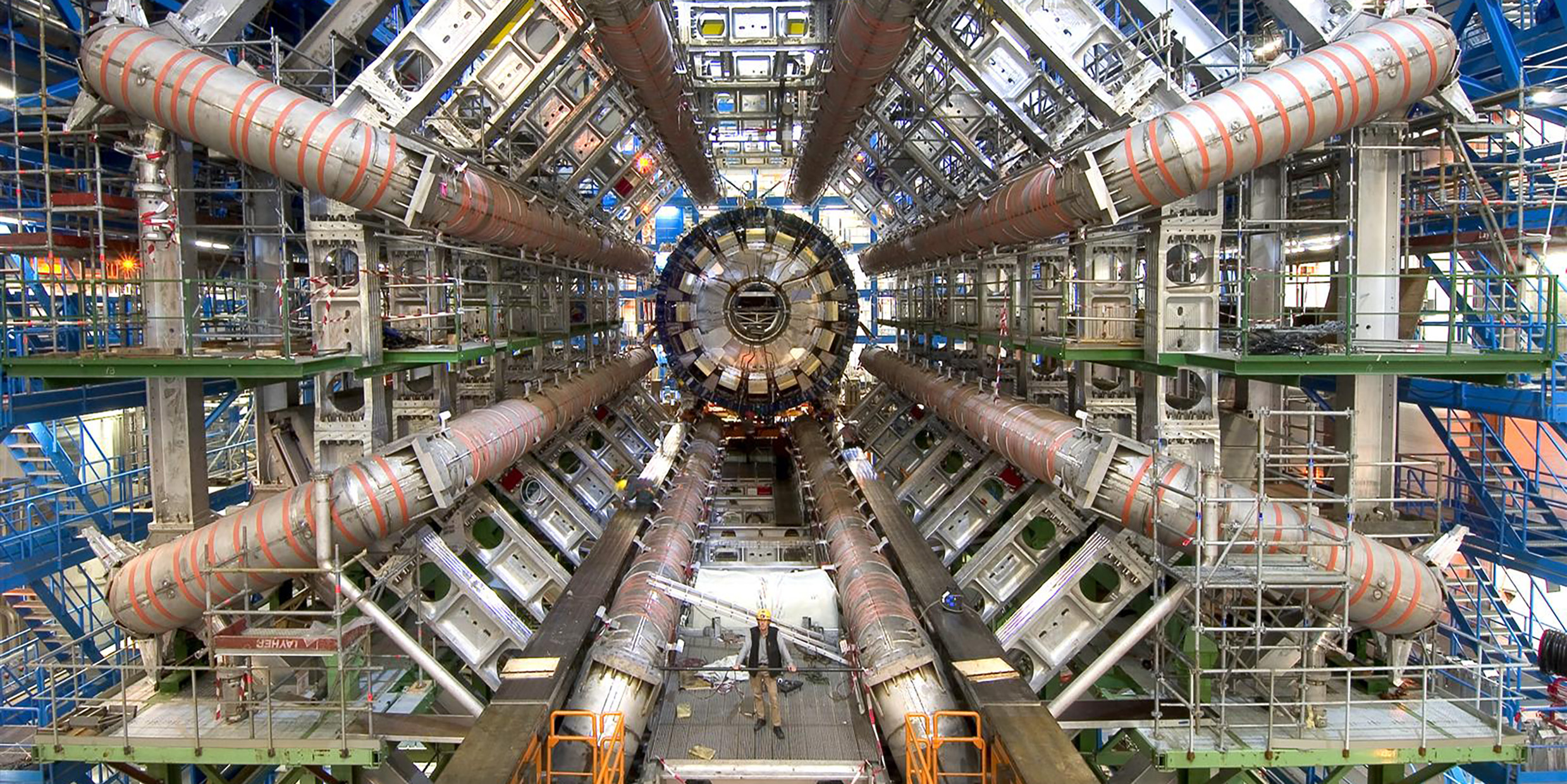

What physicists are looking for with their accelerators are the ultimate constituents of matter. They smash protons against protons, and electrons against electrons, and protons and electrons against atomic nuclei, with powerful machines such as those at Fermilab in Illinois and CERN in Europe. Out of these titanic micro-collisions comes a bewildering spray of new particles: pions, muons, neutrinos, W and Z particles — the list seems endless. Every time physicists jack up the energy of the bombarding particles, strange new stuff comes fleetingly into existence.

Behind the apparent complexity they believe they have glimpsed a kind of ultimate particle or force, called the Higgs after the British physicist who first proposed its existence, a glittering point at which all lines of explanation will converge. If the Higgs can be forced into existence, for even the tiniest fraction of a second, we would glimpse the Creator’s primal plan. Or so say the physicists.

There is just one hitch. Creating a Higgs will require a machine of staggering size and complexity, an underground oval racetrack for protons 52 miles in circumference being built in Texas, called the Superconducting Super Collider. Two beams of protons will travel in opposite directions around the ring, kept in their tracks by 3,840 magnets, each 56 feet long, and focused by 888 other magnets, the magnets altogether containing 41,500 tons of iron and 12,000 miles of superconducting cable cooled by 525,000 gallons of liquid helium. When the two hugely-energetic beams are caused to collide, the Higgs (if it exists, and if predictions of its properties are correct) will flicker briefly into existence.

The machine will cost more than $8 billion of the taxpayers’ money.

Thus the analogy with the Gothic cathedrals. After all, the cathedrals too were built at great public expense, and none of us, presumably, would wish they had not been built.

The physicists push the analogy further, suggesting religious implications for their quest. The Higgs is the “Holy Grail” of science. Leon Lederman of Fermilab calls it the “God particle.” Astrophysicist Steven Hawking suggests that if we can discover the ultimate particle or force we will know “the Mind of God.”

The quest for the Higgs, say the physicists, is the same enterprise Henry Adams perceived when he visited the cathedral at Chartres near the end of the last century: “the struggle of [man’s] own littleness to grasp the infinite.”

The analogy is breathtaking. Alas, it contains a flaw.

Cathedrals were the most prominent objects in the lives of the people who built them; they soared above townscapes; they were sites of common worship, and ritual passages of birth, marriage, and death; they were scriptures in stone, accessible to all. A requirement of every cathedral was that it should be able to accommodate the entire population of its town, from powerful lords to poorest peasants.

Accelerators are built underground, out of sight. The purpose and function of the machines is understood only by a tiny subset of the societies that build them. What happens in the machines has nothing, nothing to do with our daily lives.

The cathedrals were largely paid for by voluntary donations. Sometimes the bishop or cathedral chapter, or council, contributed substantially, and the local prince or lord might have given as well, but most of the money came from individuals. Their motive was not altogether selfless. A contribution might purchase an indulgence, a sort of redeemable spiritual coupon that would shorten the time of the donor’s future suffering in purgatory. In any case, the extraordinary sacrifices involved in building the cathedrals presumably constrained God to grant extraordinary favors in return.

Private donations or investments play no role in building accelerators. After all, what does the Super Collider offer in return? Exotic particles that exist for a tiny fraction of a second, leaving behind mere blips among data stored in a computer. Confirmation of theoretical speculations that only a few hundred physicists fully understand.

There are many good arguments for building the Super Collider — intellectual, economic, esthetic, perhaps even religious. But the cathedral analogy is a sham. The cathedrals represented a spontaneous outpouring of sacrifice and love on part of the people who paid for their construction. High-energy physicists have a long way to go in explaining their quest before they can reasonably expect similar enthusiasm and generosity from the American taxpayer.

The Superconducting Super Collider, once being constructed in Texas, was cancelled by the US Congress shortly after this essay was published in 1993. The once theoretical Higgs boson was subsequently discovered in 2012 with CERN’s Large Hadron Collider in Europe. ‑Ed.