Originally published 23 April 1984

Thoreau tells us that when he learned the Indian names for things he began to see them in a new way. When he asked his Indian guide why a certain lake in Maine was called Sebamook, the guide replied: “Like as here is a place, and there is a place, and you take water from there and fill this, and it stays here: that is Sebamook.” Thoreau compiled a glossary of Indian names and their meanings. It was like a map of the Maine woods. It was a natural history. The Indian names of things reminded Thoreau that intelligence flowed in channels other than his own.

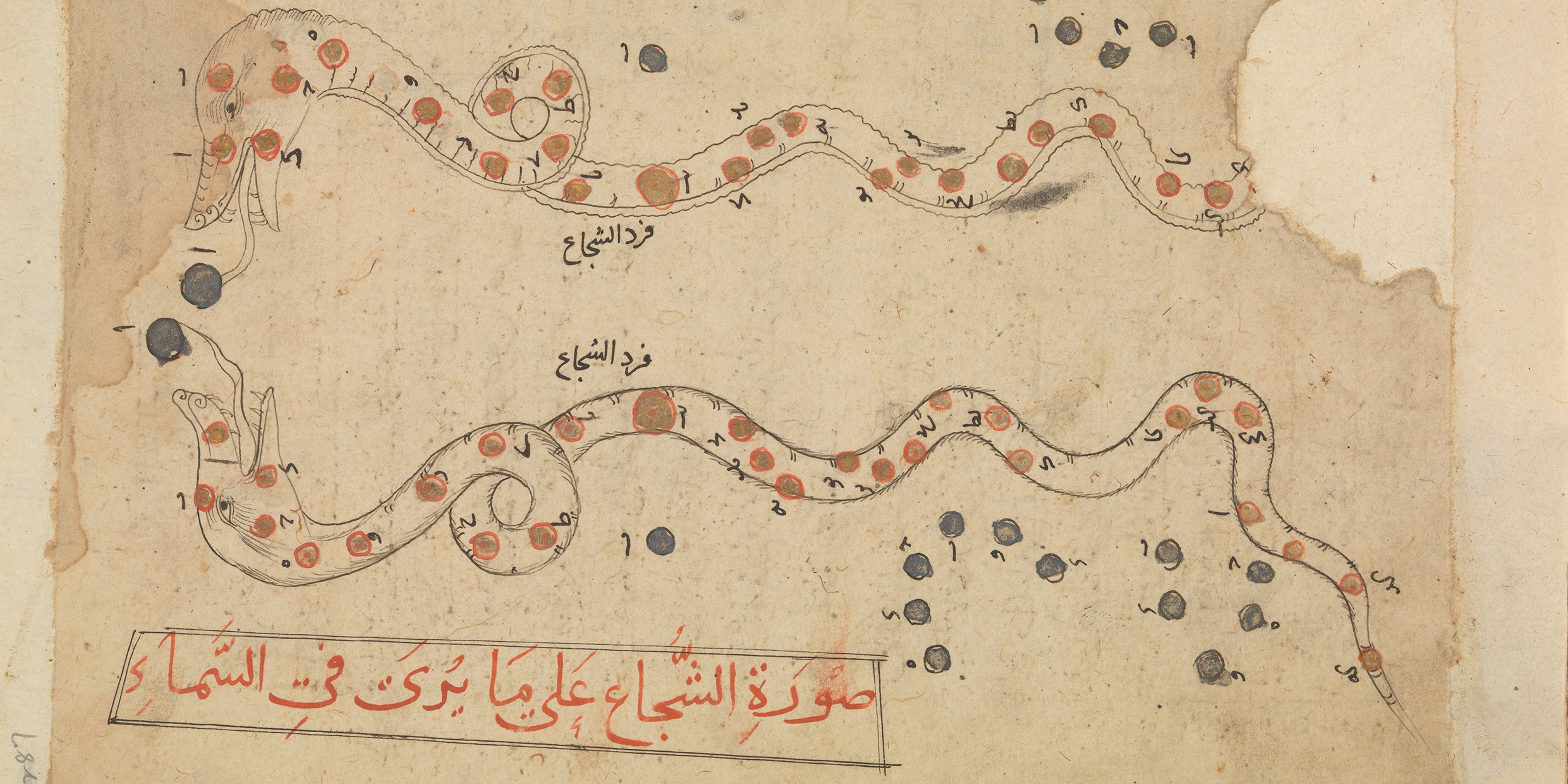

No part of our environment is so rich an archive of other intelligences as the sky. The night sky is a repository of human cultural history. The names of the stars are entries in a family album that show us what we have been and what we might become.

Some names are adjectives that describe the star. Sirius, for example, means “sparkling” or “scorching.” Arcturus takes its name from its place in the sky not far from Ursa Major; it is “the guardian of the Bear.” Some names refer to the placement of the star within a constellation. Betelgeuse, of Arabic origin, probably means “the hand” of Orion.

Most of our star names are Arabic. Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali, the “southern claw” and the “northern claw” of the Scorpion (now part of Libra), are among the more exotic examples of Arabic names. Greek and Latin names are not uncommon among the stars. Canopus is from the Greek. Capella is Latin. Nunki in Sagittarius is Sumerian and at least one star name on Western maps, Tsih in Cassiopeia, made its way from China.

Old and new

Nunki harkens back to prehistory. Cor Caroli, “the heart of Charles (II of England),” is a late arrival; Newton’s colleague Edmund Halley named the star to honor his monarch. The stars Sualocin and Rotanev in Delphinus sneaked onto sky maps when Piazzi, in his Palermo catalogue of 1814, reversed the names of his assistant, Nicolaus Venator, and attached them to stars, confounding later etymologists who puzzled over their meaning.

The classic work on star names is Richard Hinckley Allen’s Star Names — Their Lore and Meaning (1889), recently reprinted by Dover. Every serious stargazer will want to own this book. Paul Kunitzsch of the University of Munich has done much in our own time to unravel the tangled history of star names. Unfortunately, his major works have not appeared in English.

Every star name is a capsule history of our long involvement with the sky. Aldebaran in Taurus, for example, means “the follower,” from the Arabic “Al-Dabaran.” Aldebaran “follows” the Pleiades, the oasis of faint stars in the empty quarter of Taurus. When the Pleiades appear above the eastern horizon you can be sure that Aldebaran will rise an hour later at the same place and follow the Pleiades across the sky.

Translations of Greek

Most Arabic star names are translations of earlier designations of Greek origin. But Al-Dabaran was in use in Arabia before that people had any contact with classical science. The Arabs of old used stars to distinguish the seasons and to navigate featureless desert seas. The names of stars were as well known to the simple desert sailor as to the astronomers and mathematicians of Alexandria.

Other Arabic names of Aldebaran can be translated as “fat camel” or “driver of the Pleiades,” which evoke the life of a desert herdsman. The star’s Roman name, Palilicium, commemorated the Feast of Pales, the special deity of shepherds. Ptolemy called it “the Torch Bearer,” and to the Babylonians it was I‑ku‑u, the “leading star of stars.” To many modern stargazers, Aldebaran can be nothing else than the fierce red eye of the bull that charges at Orion.

Follower, driver, fat camel, red eye, the names tell us almost nothing about the star but everything about ourselves.

When classical science waned after the fall of Rome, astronomy fell into decay in Europe. It was the Arabs who kept the old traditions alive. The Arabs translated Greek astronomical lore into the language of Islam and infused the Greek tradition with lore of their own. Europeans translated Arabic texts from the late 10th to the 13th centuries. It was from these texts that we received the name of the red star in Taurus, transformed into something resembling Latin.

And so the stream of intelligence has twisted and tumbled over the uneven topography of culture, now finding one channel, now another, always flowing toward the distant ocean which is truth. Names illuminate the sky like an aurora, they enfold the stars in curtains of intelligence. It is we ourselves who give the stars their meaning. By watching. By naming. They depend upon us, says the poet Rilke, we are their transformers, “our whole existence, the flight and plunges of our love, all fit us for this task.”