Originally published 1 July 1996

From a microbe’s point of view, there is nothing more attractive than a newborn human infant. A pristine planet waiting to be colonized.

A fetus in the womb is germ-free. Not a single microbe inhabits its skin, teeth, hair, gut. Every cell is self. There are no intruders.

As the infant passes through the mother’s birth canal on its way into the world, microbes swarm aboard. A healthy woman’s vagina seethes with bacteria; a single drop of normal vaginal secretions contains a million creatures.

At the moment of birth, microbes in the environment scramble to take up residence on the new infant. Every kiss, cuddle, and suckle transmits bacteria. Within 24 hours, the infant is a teeming colony of bugs.

With the appearance of a baby’s first teeth come new opportunities for colonization. The sweaty and sebaceous secretions of adolescence make the skin a paradise for microbes. An adult human’s body is home to about 100 trillion microbial cells, 10 times more alien creatures than the number of cells in the body itself.

Biologists call our cargo of bugs our “normal microflora.” Flora isn’t quite right, since bacteria aren’t plants, and some of the our resident creatures, such as follicle mites, are definitely animals. A more accurate term is “indigenous microbiota,” because it implies a collection of microscopic creatures that are native to the body, according to microbiologist Gerald Tannock, who has written a book on the subject.

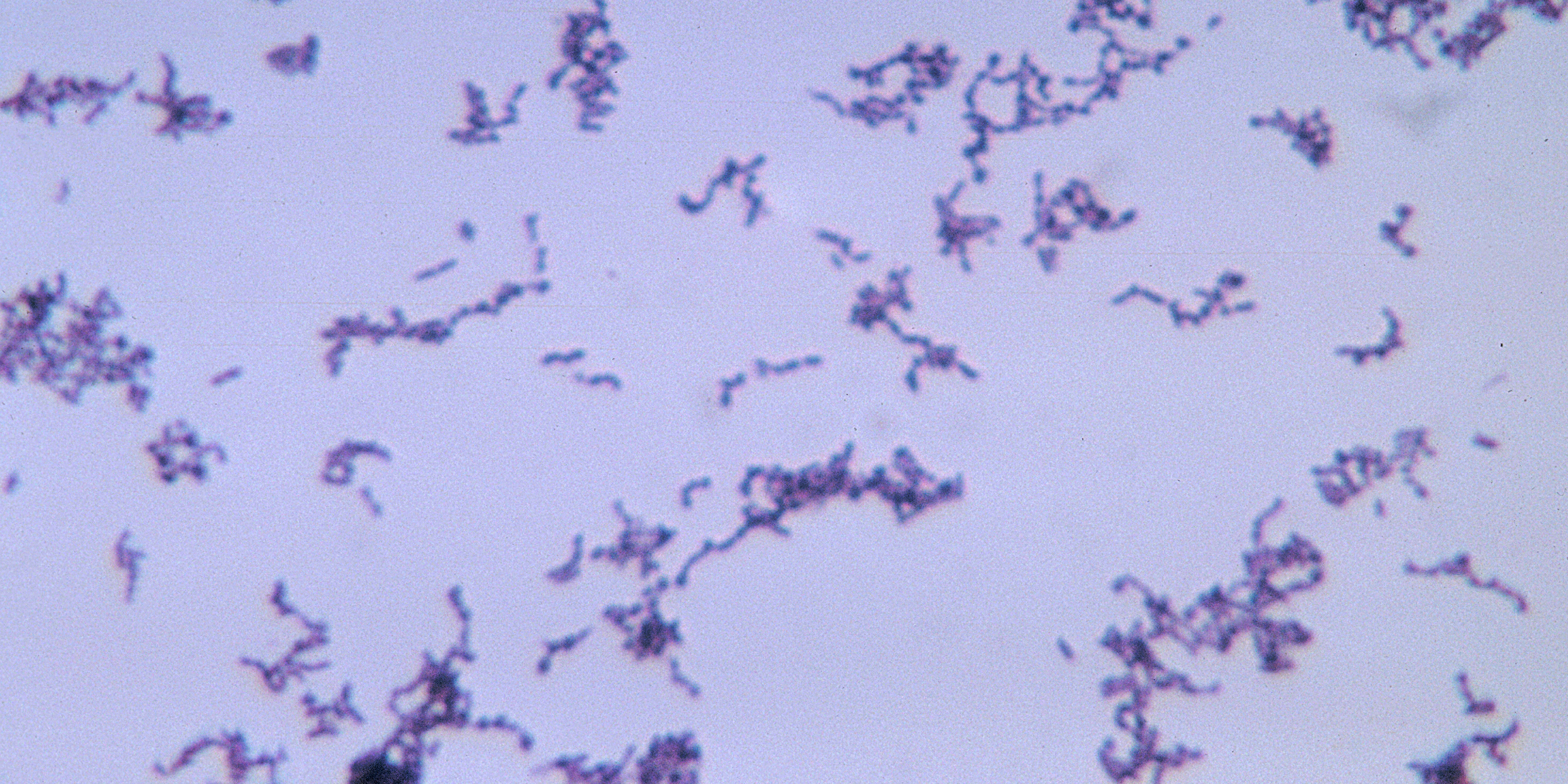

A safari through the deserts, savannas, and forests of the skin would reveal creatures with strange, unfamiliar names: Staphylococcus, Micrococcus, Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Brevibacterium, and Acinetobacter. Each epidermal resident has its preferred habitat. Propionibacterium granulosum lives in greasy areas at the side of the nose, while Propionibacterium avidium favors moist armpits.

A spelunking tour of the body would take us through the respiratory tract, the oral cavity, the gastrointestinal tract, and the outer part of the urinary tract, each with its swarming population of micro-organisms.

The human stomach and small bowel contain relatively few microbes. Generally, the acidic conditions of these organs and the swift flow of their contents keep the numbers low.

The contents of the large bowel move more slowly, with transit times of up to 60 hours, enough time for microbes to maintain thriving colonies even as vast numbers are expelled into the external world. Bacteria make up about half the contents of the large bowel, living on whatever nutrients have managed to make it that far through the gastrointestinal tract.

The bugs in our bowels produce useful vitamins, make nutrients available by breaking down complex molecules, and devour other micro-organisms that cause disease, but mostly they just go about their business, happily sharing our internal space, doing us little good or harm.

Sometimes, however, our normal microflora cause mischief. Body odor. Periodontitis. Urinary tract infection. Peptic ulcers. Trouble often begins when our internal or external ecosystem is disrupted and microbes find themselves in habitats to which they are not adapted.

Not long ago, I was required to take a three-week course of antibiotics for an internal infection. My general state of well-being was depressed while I was on the drug, and temporarily, in a somewhat different way, when I came off. I wonder to what extent my malaise during and after taking antibiotics was due to their disrupting effect on my normal microflora.

A further problem can be caused by the unrestrained dumping of antibiotics into our system. Our normal microflora develop genetic resistance to the drugs, and this resistance can be passed on to disease-producing bacteria.

There’s been lots of attention given lately to living in harmony with the macro-ecosystem — the organisms of the oceans, atmosphere and continents — but very little attention to living harmoniously with the micro-ecosystem of the human body.

Our bodies are little planets, colonized at birth, harboring hundreds of species of microbes, in staggering numbers, living in precarious balance with the host organism and with each other. How this micro-ecosystem works deserves more study by scientists, and certainly more public attention.

It is easy to find information about specific microbes, drugs, diet, and the effects of travel, but not so easy to find a good popular discussion of how all these things work together to maintain a healthy, well-balanced, self-sustaining micro-ecosystem. A book by a competent researcher called “How to Keep Our Bugs Happy” just might be a best seller.