Originally published 11 May 1998

Start with a male human cadaver.

Freeze the body rock hard. Stick it in a box and surround it with stiff foam, like the quick-hardening stuff they pour around electronic equipment to keep it steady during shipping.

Get rid of the box. Make a cut through the foam-encased body at the top of the head. Take a photograph. Slice off one millimeter of scalp. Take another photograph.

Proceed down the body as if you were slicing baloney thin. Shave a slice, take a photo. Shave a slice, take a photo. Millimeter by millimeter, down to the toes.

Nearly 2,000 slices in all. A couple of hundred pounds of human flesh and bone sliced sandwich thin.

Digitize each photograph. 2,048 pixels by 1,216 pixels, each pixel defined by 24 bits of color. 7.5 megabytes of data for each slice of the cadaver. Fifteen gigabytes in all, far more than would fit on the hard drive of a typical home computer.

A human body reduced to 15 gigabytes of 1s and 0s.

This is the Visible Human Male Project sponsored by the National Library of Medicine, a vast data set of anatomical information, perhaps the most ambitious survey of the human body since the the 1543 anatomical atlas of Andreas Vesalius.

The data set for the Visible Human Male has been available on the Internet for some time (a Visible Human Female is in the works, sliced three times thinner). Anyone with a sufficiently powerful computer and the right programming skills can display three-dimensional images of bones, blood vessels, organs, flesh — in an infinite variety of ways.

Medical students can perform virtual dissections. Teachers can illustrate human anatomy on a classroom monitor. Surgeons can practice new techniques on electronic flesh.

New applications of the data set are showing up on the Internet with increasing frequency.

I have taken a fantastic voyage through the Visible Male’s colon, sailing along a seemingly endless tunnel, perusing every bump and polyp.

I have seen skull and flesh peeled away to reveal the structure of the eyeball and optic nerves.

I have flown around exposed muscles and bones of the thigh as if on a spaceship visiting a distant planet.

But none of these Internet animations quite prepared me for spending an evening with the book version of those 1,878 human slices: the National Library of Medicine’s Atlas of the Visible Human Male: Reverse Engineering of the Human Body, by Victor Spitzer and David Whitlock of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center (Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 1998).

Twelve slices to a page, in living color. The first image is a gray slip of skin from the scalp. The last is a tiny patch of skin from the fifth toe of the left foot.

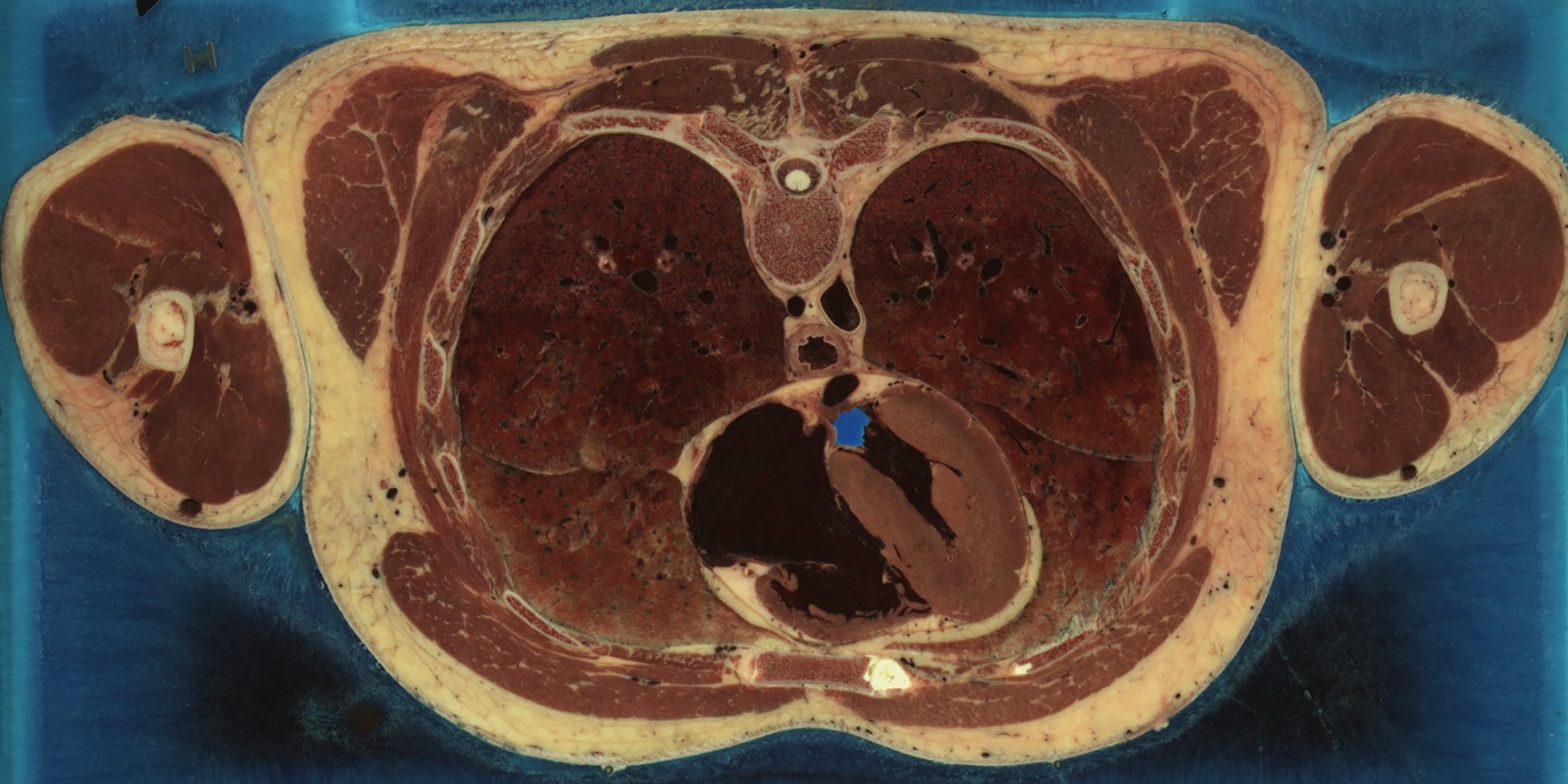

We are used to seeing human anatomy made visible as entire systems or complete organs — the skeleton, the nervous system, the circulatory system, the digestive system. In the Atlas of the Visible Human Male we see the body as slices of red meat, as if we were browsing in a butcher shop.

For example, a slice through the thighs looks like two fine sirloin steaks ready for the grill, with a circle of bone at the center and a margin of white fat. The effect is disconcerting.

I think of Hamlet’s despairing complaint: “What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals! And yet…”

And yet! And yet this paragon, this angel is here reduced to meat sliced thin, digitized, stored on disk as 15 gigabytes of soulless bits.

It is perhaps good to remember that this meat was a man. Joseph Paul Jernigan. A convicted serial killer, executed in Texas by lethal injection, who donated his body to science. How “like an angel” were his actions in life was decided by the Texas justice system. But at least give Jernigan this: His gift to science will serve the education of thousands of medical students worldwide.

However bizarre its origin and gruesome its aspect, the Atlas of the Visible Human Male will advance the quality of life of humankind.

But perhaps the atlas’s most useful function is to make us consider with more reverence what it does not contain. The soul of man cannot be reduced to bits, at least not to the paltry 15 gigabytes of the Visible Human Male.

“The power of the visible is the invisible,” says the poet Marianne Moore. How many gigabytes of gigabytes it would take to portray the soul in all of its nobility, its angel-like beauty, its godlike apprehension — and its sometimes diabolic aberrations — remains to be accounted. Perhaps not infinite, as Hamlet suggests, but certainly beyond the accounting of this or any foreseeable data set.