Originally published 13 April 1992

Recently, in a fit of nostalgia, I purchased copies of Popular Science and Popular Mechanics from the newsstand.

I hadn’t read these magazines for nearly 40 years, not since my teens. Back then, I read them voraciously. They were part of the reason I decided to study science and engineering in college.

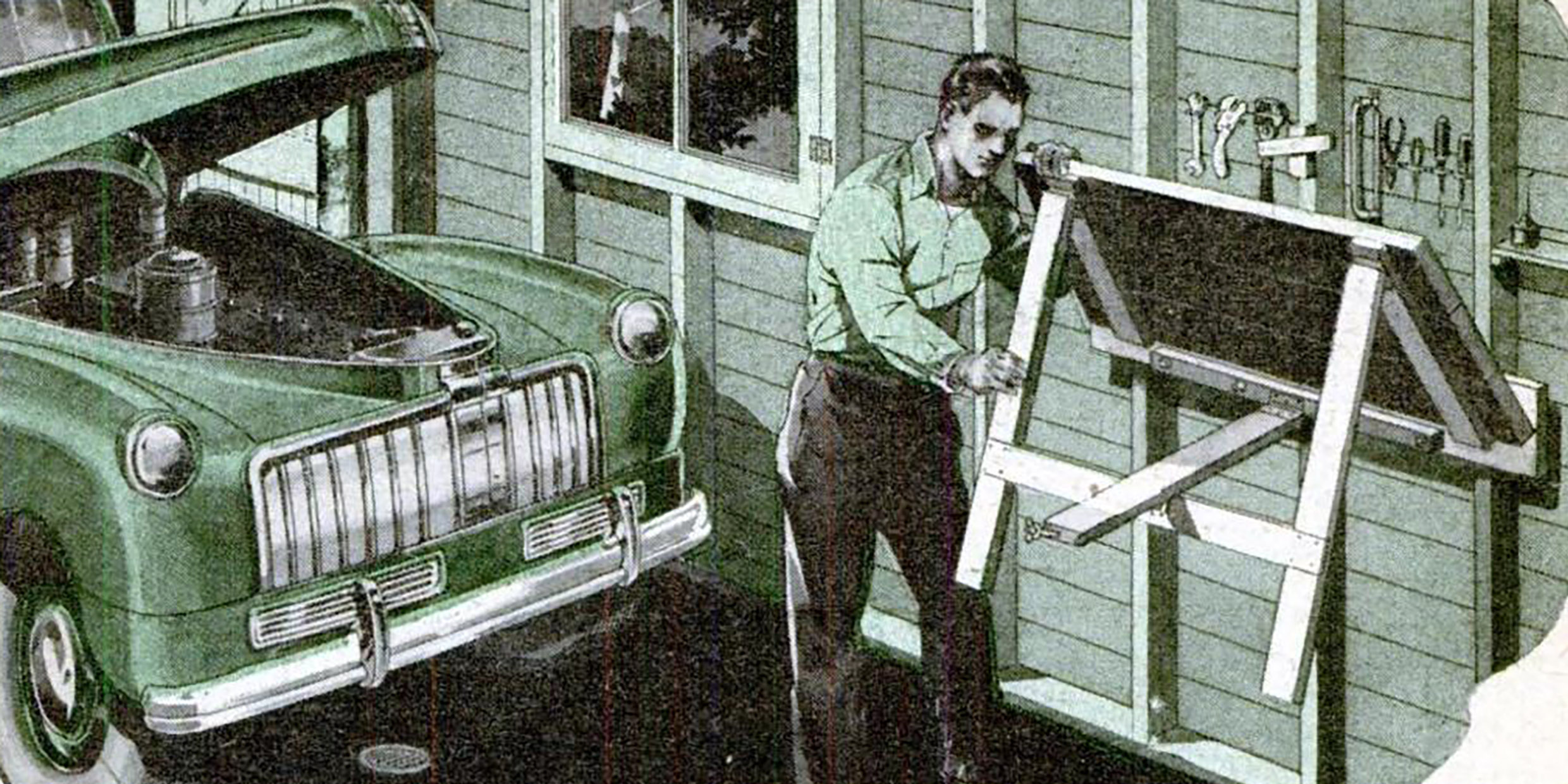

My father brought these magazines into our house. He was the quintessential popular scientist, an engineer with a knack for tinkering. Our basement was fitted out as his workshop — a workbench, power tools, a hundred bottles full of fasteners, washers, gaskets and thingamabobs of every sort. Nothing mechanical or electrical was ever discarded at our house; my father squirreled everything away. “You never know when something like this might come in handy,” he used to say.

The muses that inspired

In a corner of the workshop was an ever-growing pile of Popular Science and Popular Mechanics. These were the sources of his prodigious inspirations, the muses that inspired his many projects. A new way to keep the gutters from clogging up with leaves. A new way to twiddle the carburetor to make the car run smoother. A new jig for cutting pickets for a fence. Popular Science and Popular Mechanics kept my father on the cutting edge of gimmickry.

To his pile of well-thumbed magazines I often retired for entertainment. During long afternoons I sat huddled under the basement stairs reading about the latest innovations in high and low technology. As I recall, cover stories almost always featured some futuristic mode of transportation: electric automobiles, ocean-going hovercraft, folding-wing airplanes that would fit in the family garage. News-notes featured such things as multi-tipped screwdrivers, self-flushing toilets and sprayed-concrete houses.

It was from these magazines, also, that I first heard about computers, radio astronomy, atomic energy, and space flight. That nook under the basement stairs wasn’t a bad place to get an education.

And, now, 40 years later, I’m pleased to see that nothing, really, has changed. The magazines still contain the engaging mix of slick technology and serious science that made the science seem positively palatable to the teenager. Here too is the same gee-whiz utopianism that fed the teenager’s sense of optimism and wonder.

Just look at some of the items featured in [1992] issues of Popular Science and Popular Mechanics:

NiteMates flashlight slippers, to avoid mishaps on those midnight forays into the kitchen. Simply tap your heels to light the krypton bulb in the toe of each slipper.

A bedside alarm clock that shuts off the alarm for four minutes when you speak to it roughly.

A General Motors prototype automobile that gets 100 miles to the gallon.

A NASA workhorse rocket for the 21st century.

And, yes, here too are other things I remember from my youth:

The goofy ads for everything from elevator shoes to 12-in‑1 multitool survival knives.

Plans for building your own gyrocopter or ornamental bird bath.

Two-page, full-color ads for spark plugs and faucets.

Popular Mechanics was founded in 1902. Popular Science goes back to 1872. Both magazines contain a “Looking Back” feature — a page of excerpts from issues of 25, 50 and 100 years ago for Popular Science, and 30, 60 and 90 years ago for Popular Mechanics. The 30th Anniversary issue of Popular Mechanics, published in the depths of the Great Depression, contained articles on “Machines to Raise Wages” and “Luxuries for Everyone.” As far as I can tell, both magazines have maintained a clear sense of their mission since issue number one: praise the practical, exalt American ingenuity, and keep an upbeat attitude about the future.

A hearty celebration of the practical

Yes, there is something vaguely jingoistic, white, and male about the magazines, but you won’t find politics in these pages, or racism, or macho-swagger. Just contrivances, contraptions, widgets, doohickeys, and a hearty celebration of practical science and state-of-the-art technology. I’ll bet I’m not the only kid who was nudged toward the study of science or engineering by these magazines.

It was fun to peruse them again, to see that nothing has changed, and to regret that I have been so long out of touch.

Reading the current issues of Popular Science and Popular Mechanics I am suddenly back under the basement stairs, rummaging through my father’s old issues of the magazines, circa 1945 – 1950, and imbibing a down-to-earth philosophy that has served me well for 40 years: Happiness is unclogged gutters and spark plugs that are perfectly gapped.