Originally published 30 September 1991

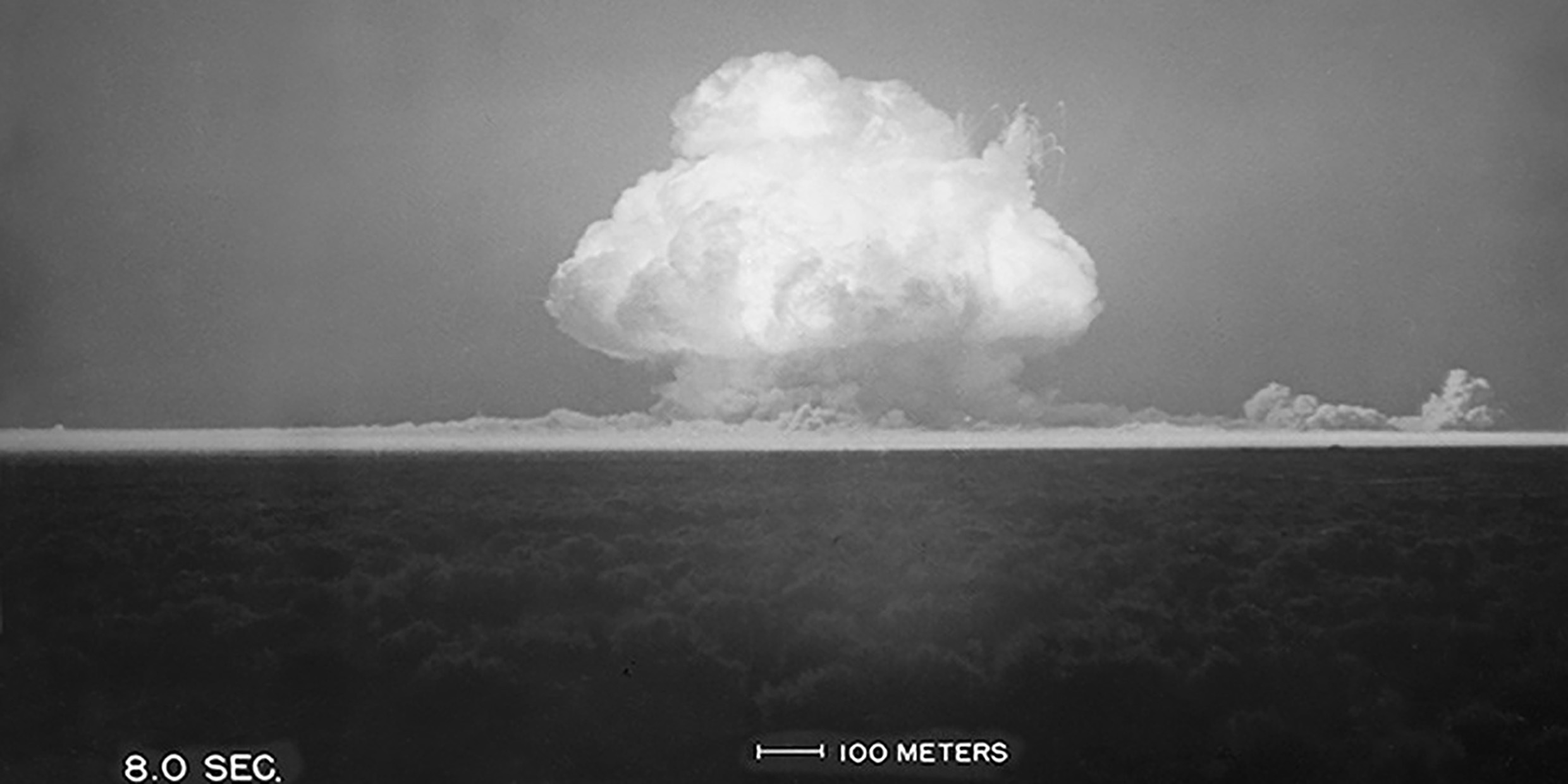

At 5:29 a.m. Mountain War Time on July 16, 1945, the world’s first nuclear explosion occurred on the Alamogordo bombing range in the desert near White Sands, New Mexico.

A bubble of blinding light inflated on the horizon. Within seconds, a mushroom of roiling gases rose into the heavens. Hurricane winds blew across the desert floor. Surrounding mountains echoed with the roar.

It was impossible to keep such an explosion secret. The shock broke windows 120 miles from ground zero. The Army had an explanation: A munitions storage dump had accidentally exploded.

Some dump! Some accident!

We found out what actually happened 20 days later when a second bomb exploded over Hiroshima, Japan. The news caused a special stir in Eastern Tennessee, where I grew up. For several years, we had heard rumors of strange goings on at a place called Oak Ridge, near Knoxville. Now we were told that the enriched uranium for the Hiroshima bomb had been produced at Oak Ridge, and felt pride that our region had contributed so decisively to the defeat of Japan.

That sense of achievement had its price.

Deadly pollution

In 1983, the Department of Energy revealed that over the years since the war, 1,200 tons of toxic mercury was released into the environment from the nuclear weapons facility at Oak Ridge.

More revelations came in 1987: a catalog of deadly pollutions — polychlorinated biphenyls, heavy metals, radioactive particulates and gases — released into the air and dumped into the earth. The price of quick victory over Japan, and of American security during the Cold War with the Soviet Union, was a landscape contaminated with toxic chemicals and radioactive wastes, unfit for plants or animals, a grim geography of death.

And Oak Ridge wasn’t the worst.

This country’s premier nuclear wasteland is the Hanford Nuclear Reservation on the Columbia River in Washington state, where the plutonium for the Alamogordo test bomb and the Nagasaki bomb was produced. For 40 years, Hanford officials knowingly poisoned the air and water of that region with radioactive gases and liquids, all the while denying any public risk.

Today, Hanford is a simmering moonscape of buried wastes. Some waste tanks are apparently in danger of catastrophic explosion.

Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; Rocky Flats, Colorado; Savannah River, South Carolina; Fernald, Ohio; Weldon Spring, Missouri; Yucca Flat, Nevada; Bikini and Enewetak Atolls, Pacific Ocean: They are the fouled nests of the nuclear animal.

The blighted landscapes of the nuclear age have been recorded in a brilliant collection of color images by photographer Peter Goin (Nuclear Landscapes, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991). Goin gained access to the Hanford plutonium production facilities, the Nevada test sites, and the Pacific test sites. By a kind of visual magic, his spookily lifeless photographs let us sense what the camera cannot see.

The invisible emanations. Plants and animals that bear in their tissue the ticking time bombs of radioactive decay. Contaminated water, metal and concrete. Soil saturated with the stuff of death. Not a single human appears in Goin’s bleak landscapes, and for good reason. Even the photographer’s brief presence in these places was not without risk to himself.

Costly cleanup

The Energy Department recently proposed a 30-year plan to clean up the nuclear mess. The first five years are expected to cost upwards of $40 billion, a staggering amount of money that Congress will be reluctant to grant. So far, most of the effort has been spent cataloging polluted sites, perhaps as many as 3,000 on the Hanford Reservation alone.

Thirty-four states and Puerto Rico are affected. No one knows the full extent of the problem.

And what about the Soviet Union? If the Cold War left America in such a mess, imagine the problem the Soviets will face when finally democratization and public scrutiny pulls aside the curtain of secrecy that has masked more than 40 years of weapons production and testing.

Of course, there is no such thing as a real solution. Radioactive and toxic wastes can only be moved to presumably safer sites, assuming such sites can be found, and with risk to the human workers who do the moving.

If we are lucky, the end of the Cold War will slow the awful frenzy of nuclear weapons production that has been our species’ shame. But even if production were stopped completely, the planet has been fouled for thousands of years and billions of dollars spent on clean-up won’t change that.

As that first bright bubble of nuclear energy swelled to fill the predawn sky in the New Mexico desert 46 years ago, scientists and their military patrons had already made a mess of things. The mess would get worse with each passing decade.

Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, watched that morning as the multi-colored mushroom rose into the sky, brighter than a thousand suns; he thought of a quote from an ancient Hindu scripture, “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

Now we must become Life, the cleaner-up of messes.