Originally published 27 June 1994

You may want to stop reading now.

I want to talk about microbes. And to start with, I want to talk about the microbes that inhabit the human body.

They are everywhere: eyes, ears, teeth, gums, between the toes, in the groins. We are their planet. They harbor by the millions in the grasslands of the skin, the forests of the scalp, the rain forests of the armpits.

Most densely of all, they thrive in the caverns of the digestive tract. In the lower part of the large intestine there are commonly 100 billion bacteria per gram of excrement (a gram is about half the mass of a dime). A substantial part of our body weight is the bugs who live on us and within us.

They are the cause of body odor, bad breath, and intestinal gas. When their populations get wildly out of control they cause maladies such as yeast infections and thrush. But mostly they are harmless. Biologists call them commensal, which means in its Latin root, “eating at the same table.”

Indeed, they are better than harmless; they are positively beneficial. Our resident microbes manufacture vitamins, stimulate the immune system, and fill body niches that might otherwise be invaded by disease-causing organisms. We could not remain healthy without them.

In other words, we would be in a fix without our invisible bugs.

Long before anyone knew that microbes exist, humans made use of their talents. They help us make and preserve cheese, yogurt, bread, beer, and wine. They prepare flax plants for the making of linen. From Day One, microbes have been an unrecognized cornerstone of human economy. Try to imagine civilization without wine and cheese on a linen cloth.

And more. Much more. We now realize that the oxygen we breathe was put into the air by microbes. All plants, including the food we eat, need nitrogen; but no plant can take nitrogen directly from the air. Plants depend upon microbes in the soil to “fix” atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form.

The timber with which we build our houses could not grow without the fertilizing effects of microbes in the soil. Our fossil fuels — oil, gas, and coal — would not exist without microbes. Commercial deposits of iron, and perhaps even gold, owe their existence to the activities of bacteria.

Our planet could get along very well, thank you, if humans suddenly vanished from its face. But without the vast, seething, invisible mass of microbes that inhabit every inch of its surface, Earth would be as dreary as the surface of the moon.

Lynn Margulis, a biologist at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, has made herself the poet/historian of microbes, chronicler of their unseen goings-on, praiser of their hidden beauty. With her son Dorion Sagan, she has published several books sharing with us her prodigious knowledge of the one-celled creatures. No race of visible beasts on Earth has had a more ardent friend.

“We have done well separating ourselves from and exploiting other organisms,” write Margulis and Sagan, “but it seems unlikely that such a situation can last… We must slow down, share, and reunite ourselves with other beings if we are to achieve evolutionary longevity.”

By other beings, they mean primarily microbes.

The knowledge garnered by Margulis and her microbiology colleagues is necessary if we are to preserve the planetary environment of which microbes are so fundamentally a part. However, that same knowledge offers opportunities for further environmental disruption.

Having discovered the microbes, probed their lives, and understood how they eat, move about and reproduce, humans are now ready to embark upon the greatest exploitation of all: to harness the chemical processes of microbes on a scale that will dwarf the making of cheese, beer, and linen.

Microbes will be used to extract minerals from ores, produce foodstuffs, manufacture chemicals, generate electricity, treat wastewater, clean up pollutants, and protect crops from frost — for starters.

If a microbe cannot be found in nature that can perform a specific task, then technologists will genetically engineer a bug that can.

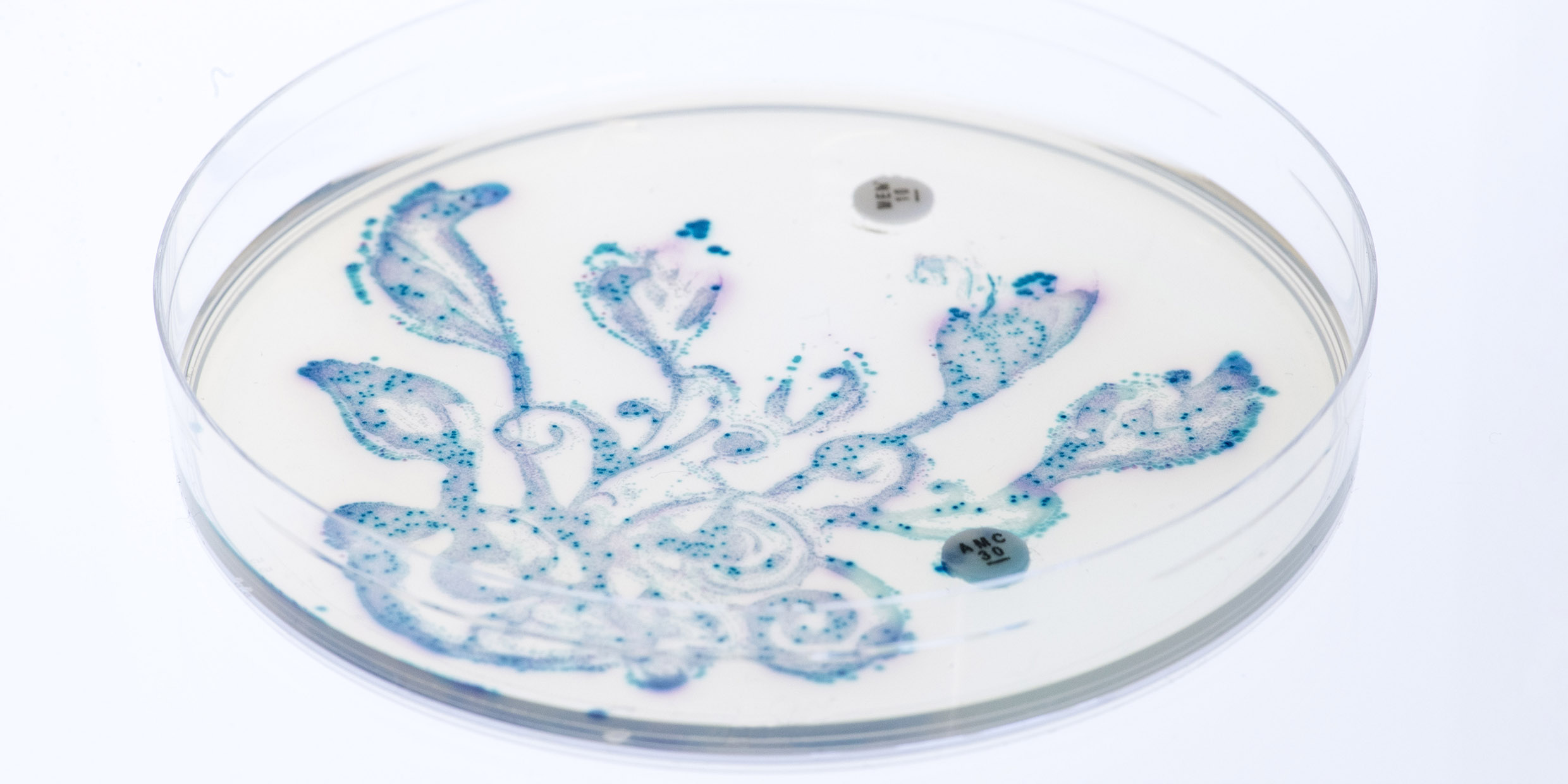

Many bacteria have already been genetically modified. Escherichia coli, the most common microbial inhabitant of the human gut, has been fiddled with to make it effective at a dozen industrial tasks, from breaking down toxic chemicals to the production of dyes.

No more eating at the same table without going to work.

In many cases, it will be necessary to release genetically modified microbes into the environment if they are to achieve the desired result. The ecological consequences of release are not yet well understood. We may succeed in cleaning up some of the messes we have made; we may make bigger messes.

We stand at an awesome crossroads in the history of life. The industrial exploitation of microbes can be filled with promise, or fraught with danger.

It is unlikely that anything we do will have much effect on the survival of the invisible organisms that had the planet to themselves for most of Earth’s history. As Margulis and Sagan suggest, it is our own survival that is in jeopardy.