Originally published 30 April 1984

“Look at the stars! Look, look up at the skies!” says the poet Gerald Manley Hopkins. “O look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air! The bright boroughs, the quivering citadels there! The dim woods quick with diamond wells; the elf-eyes!”

The lights in the night sky, the stars like elf-eyes, the bright galactic boroughs, have long been the inspiration of myth-makers, philosophers, theologians and poets. Until recently, bright lights in the dark sky were also the astronomer’s only window on the universe.

The development of radio telescopes half a century ago threw open another window. Astronomers could now view the universe in a different kind of “light” invisible to the human eye, the long wavelength end of the electromagnetic spectrum. An astonishing series of discoveries followed: quasars, pulsars, maps of the Milky Way Galaxy, the afterglow of the Big Bang.

Visible light and radio waves are the only parts of the radiation spectrum that penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere. When it became possible to loft telescopes into orbits above the atmosphere, still more windows were opened. X‑rays and ultraviolet light revealed a universe of exceptional energy and violence: galactic nuclei wracked by cataclysms, matter spinning into black holes, stupendous turbulence on the face of the Sun.

Infrared survey

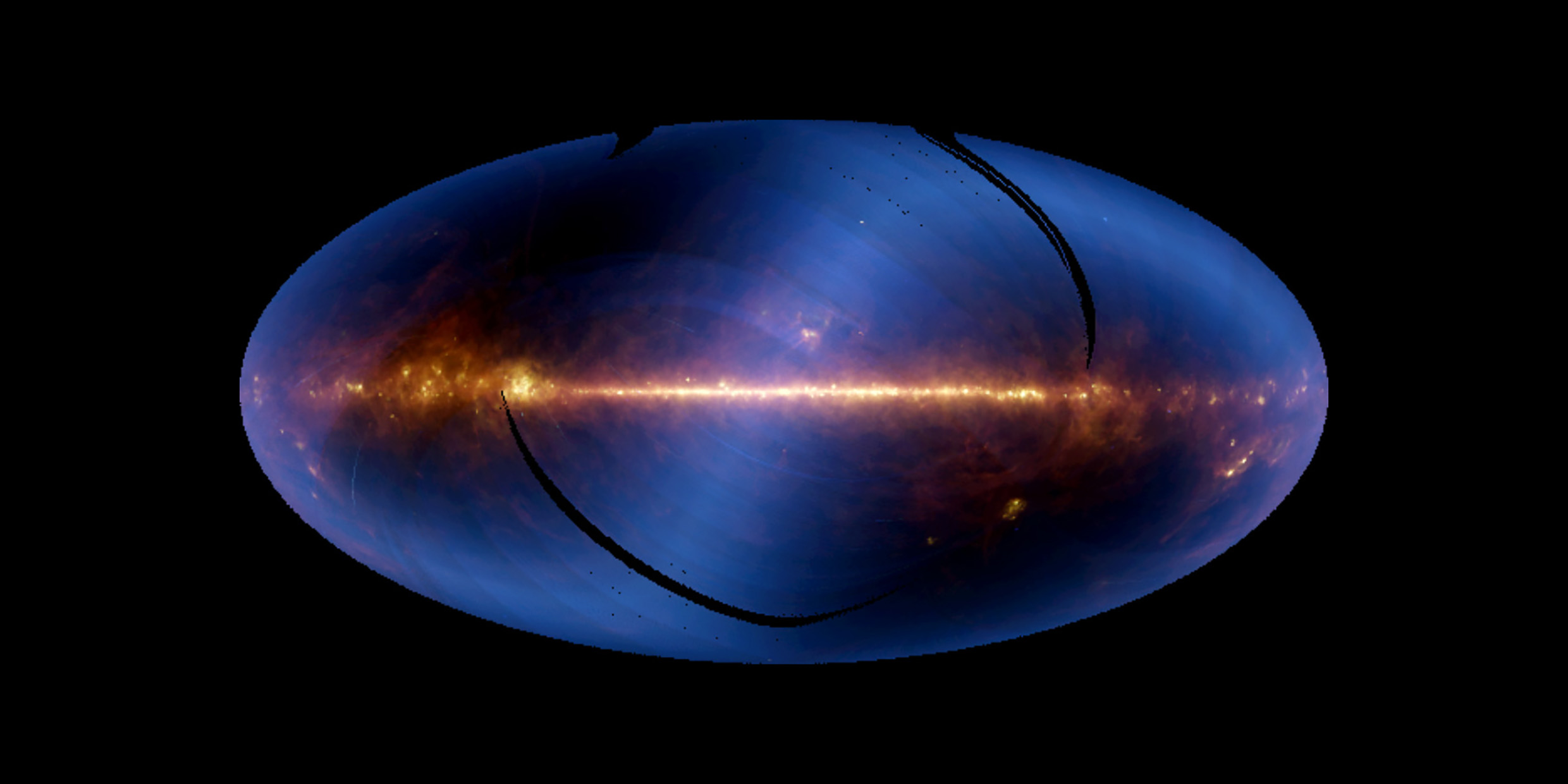

Recently, a new season of surprises has been initiated with the first detailed survey of the sky at infrared wavelengths. A highly sophisticated Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) was launched into orbit in January 1983 by a team of astronomers from The Netherlands, the United States and the United Kingdom. The telescope was 100 times more sensitive than previous infrared instruments. It functioned almost perfectly for 10 months until its liquid helium coolant ran out in November. During that time, the telescope made a systematic infrared survey of 98 percent of the sky, and took a closer look at certain preselected objects.

Infrared radiation is a sensitive indicator of the cold solid material in the universe. In order for the detectors not to be blinded by the warmth of the satellite itself, it was necessary to cool them with liquid helium to a temperature of minus-455 degrees Fahrenheit (a few degrees above absolute zero).

IRAS revealed the vast and unexpected realms of cool particulate matter distributed throughout the universe.

Comets, for example, turn out to be much dustier than previously supposed. The first comet discovered by IRAS came within 2 million miles of the Earth, closer than any other comet of recent centuries. The telescope showed the comet carried a coma and tail of dust that extends hundreds of thousands of miles beyond the optically bright nucleus. The dusty envelopes of other comets were discovered at the rate of one a month, comets too faint to be seen in visible light. The solar system’s population of comets may be more numerous than we had imagined.

IRAS revealed a three-layered ring of dust surrounding the Sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. The ring probably resulted from the multiple collisions of asteroids from the asteroid belt.

The Sun is not the only star ringed with dust. One of the most intriguing discoveries of IRAS was a disk of cold rocky material around the bright star Vega. Vega is a relatively young star and astronomers believe the dusty halo may be a solar system in the process of formation.

Stars’ birthplace

The list of discoveries made by IRAS is long and exciting. The satellite studied dense knots of cool dust and gas in the galaxy that are thought to be the birthplaces of stars, dim woods that hide new diamond wells. The satellite examined the shrouds of gas that massive stars blow off in their old age. The Milky Way galaxy was found to contain unexpected galaxies, other quivering citadels of luminous stars, also showed new dark details of variation and structure.

Some of the point sources discovered by IRAS have no optical counterparts; no stars, nebulas or galaxies can be seen at the point of infrared emission. These mysterious sources may be distant members of the solar system, moving in languid orbits far out beyond Pluto. They may be faint cool members of the realm of the galaxies, or stars cloaked in dusty shells. They might represent a previously unknown class of celestial objects, cool objects that have waited until now to reveal themselves.

IRAS’ images of the cooler components of the universe, color-coded by temperature and displayed on computer screens, are as dazzling as any of the long familiar bright objects in the night sky. The new infrared telescope has shown that the “fire-folk sitting in the air” sit on dark and dusty thrones.

Since the end of the IRAS mission in 1983, there have been several subsequent infrared space telescopes launched into orbit, including the WISE space telescope in 2009, which was many times more sensitive than IRAS. ‑Ed.