Originally published 14 November 1988

Several recent surveys suggest that America is a nation of science illiterates.

The Public Opinion Laboratory of Northern Illinois University polled 2,041 adult Americans for the National Science Foundation. More than half of those surveyed did not know that the Earth goes around the sun in one year. Twenty percent believed the sun orbits the Earth. Another 17 percent thought the Earth goes around the sun once a day.

Asked whether electrons were smaller than atoms, less than half said yes. Twenty percent said electrons were larger than atoms and 37 percent did not know. One out of five Americans believes sound travels faster than light.

In another poll conducted by the National Science Board, nearly half of respondents disagreed with the statement that humans evolved from earlier forms of life. About the same proportion believe that rocket launches affect the weather and that certain numbers are lucky for some people. This is all pretty basic stuff, and indicates not only a failure to assimilate scientific information, but also a certain disconnectedness from the underpinnings of modern civilization.

A personal theory

Undoubtedly, every science educator has a pet theory to explain why so many Americans are ignorant of basic science. As one who makes his living communicating science — as a teacher and a writer — let me add my two-cents worth to the debate. I’ll begin with a personal anecdote.

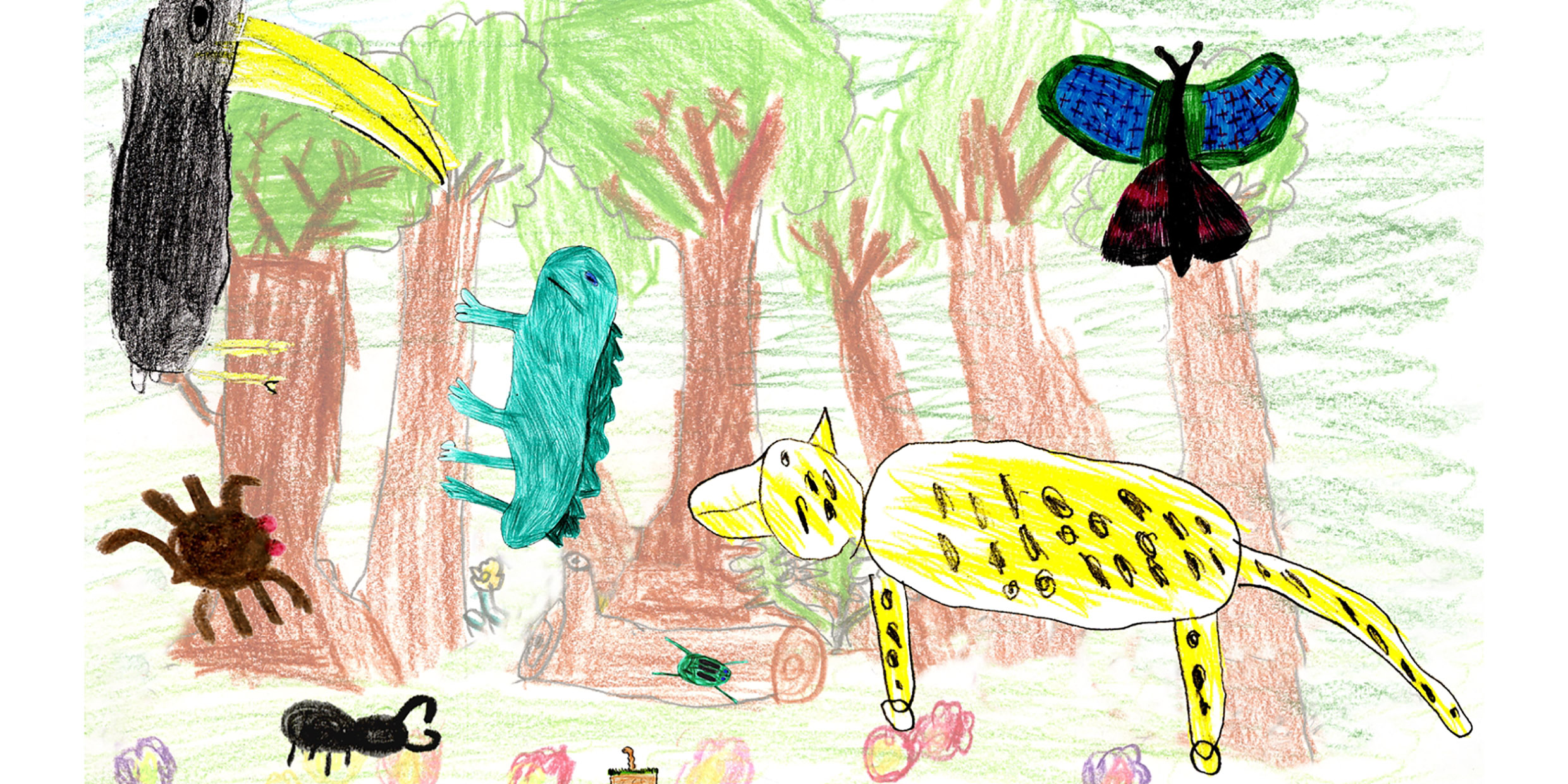

When my kids were young they were lucky to have a year of schooling in London, England, and another year in Ireland. An important part of the curriculum in both schools was drawing from nature. Teachers took the students to the park or seashore to sketch what they found — bugs, leaves, blades of grass, shells, stones. The emphasis was not on art, but on observation; not on self-expression, but on faithful representation. The children were encouraged to look, see, and record what they saw.

In London we lived near the British Natural History Museum, a vast Victorian storehouse of natural diversity — stuffed animals by the thousands, glass cases full of glistening beetles and gaudy butterflies, room after room of dinosaur bones, rocks, gems, and fossils. The teachers encouraged the children to go there on Saturdays. For the deposit of a large English penny they were given a folding canvas stool, a drawing board, paper, and a fistful of colored pencils. Off they went into the depths of that cavernous building to sketch hummingbirds and pterodactyls.

Not once in American schools were my children asked to draw from nature. They had art classes, yes, and good ones. They sketched sneakers, bottles, and bowls of bananas — still lifes in the classroom. In biology lab they drew what they saw under the dissecting microscope. But no teacher took them into a natural environment with pencil and paper. They were never asked to sit and sketch a mushroom in the woods.

It is my impression that the British and Irish emphasis on drawing from nature had two objectives: developing the child’s powers of observation, and reinforcing the child’s curiosity about the natural world. Observation and curiosity are ideal foundations for the study of science.

The child who has watched the motions of the stars and planets will find it easier to appreciate that the Earth goes around the sun. The child who has observed the clouds, their heapings and tumblings, their dark massings and silver linings, will be better prepared to understand the relationship between rocket launches and weather. The child who has considered the beauty of a heron rising from the pond and the cunning of the spider’s web will be less reluctant to acknowledge our evolutionary relationship with the lower animals. And the child who has paid close attention to the threads of causality that stitch nature together will be properly skeptical of lucky numbers.

More than just a method

Perhaps the reason we are disconnected from science is because we are disconnected from the natural world that science describes. Science is not just a body of information. And science is more than a method. Yet these are frequently the only things that are taught in the schools.

Scientific information and scientific method are important and must be taught, especially in the upper grades. But more fundamentally, science is a set of attitudes about the world.

Science is respect for the evidence of the senses — seeing things as they are, and not as we wish them to be. Science is the conviction that the world is ruled by something more than mere chance and the whims of gods. Science is confidence that the human mind can make some sense of nature’s complexity. And science — almost paradoxically — is humility in the face of nature’s complexity.

Until students have assimilated these attitudes, they will be distrustful of scientific information and skeptical of scientific method, and we will continue to be a nation of science illiterates. These attitudes are not things a teacher can teach. But they are taught by nature. And that’s why I am grateful to the British and Irish teachers who sent my kids out into nature with sketch pad and pencil — to observe, describe, and learn.