Originally published 23 April 1990

The first wildflowers of the spring are small, inconspicuously colored, and inclined to bashfulness. The wood anemone and starflower, two of my favorites, unfold their blossoms tentatively, as if testing the temper of the air. They hesitate in woody shadows, like young ballerinas waiting in the wings for some more-colorful prima donna to take the stage.

Later in the season we will have more conspicuous displays — fields of raw gold, purple marshes, towering spikes of crimson — but no wildflowers are more welcome or more beautiful than the unassuming pioneers of April and May.

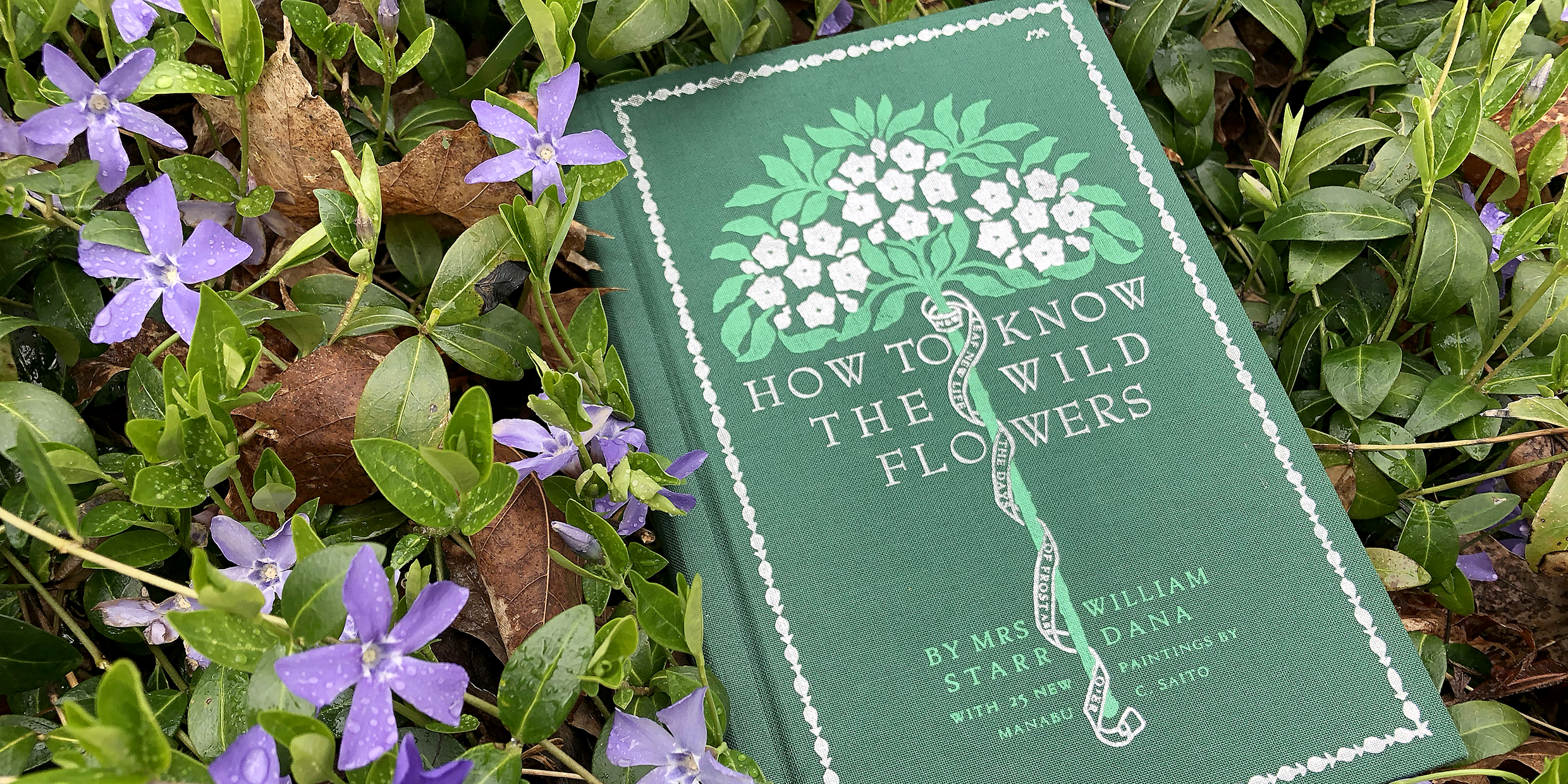

The same might be said for the first wildflower guide, Mrs. William Starr Dana’s How to Know the Wildflowers, published in 1893 by Charles Scribner’s Sons, and reissued in a handsome boxed edition by Houghton Mifflin. There are field guides which are more comprehensive, authoritative, and up-to-date, but none which captures the delicacy and charm of Mrs. Dana’s original. Naturalists who have not previously acquired How to Know the Wildflowers from a flea-market stall or second-hand bookstore now have the opportunity to add this wonderful book to their library.

Let’s give the author her own name, Frances Theodora Smith. She was born in 1861 and brought up in New York City. Her love for wildflowers was acquired during summers spent with her grandmother in Newburgh, New York, not far from the home of the famous naturalist-writer John Burroughs.

A young widow

While in her early 20s, Frances Smith married William Starr Dana, a naval officer much older than herself. The marriage was happy, but the husband soon died of influenza. Victorian convention dictated a long period of mourning, widow’s weeds, and retirement from society. As a distraction from grief and imposed social inactivity, Mrs. Dana took up again her old interest in natural history.

In those days the only source of information about wildflowers was technical works such as Gray’s Manual of Botany. Field guides for the casual observer simply did not exist. But the need was there, and Mrs. Dana found her inspiration in a magazine article by her old neighbor John Burroughs.

“Some of these days, ” wrote Burroughs, “someone will give us a handbook of our flowers, by the aid of which we shall all be able to name those we gather on our walks without the trouble of analyzing them. In this book we shall have a list of all our flowers arranged according to color, as white flowers, blue flowers, yellow flowers, red flowers, etc., with the place of growth and the time of blooming.

Mrs. Dana took up the task and created a handbook that has been a model for all that came after. Her friend Marion Satterlee supplied delicate pen and ink drawing to complement the text. The first printing sold out in five days, and the cloth-bound book stayed in print until the 1940s. With the new edition from Houghton Mifflin, the book will have been in print for a century, surely a record for a book of this sort.

What gives the book its enduring charm are the brief essays describing each flower, written in the best tradition of Victorian natural history — warm, literate, anecdotal. Mrs. Dana frequently quotes Greek and Roman authors, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and of course the New England poets and essayists — Longfellow, Whittier, Thoreau, and Emerson. To read her book is not only to learn the wildflowers; it is also a stroll down the primrose path of cultural history.

Wildflowers and poetry

What of the wood anemone, that exquisite flower that even now graces the verges of our woods? The name means “wind-shaken,” we learn from Mrs. Dana. We are given a snip of William Cullen Bryant:

—Within the woods, Whose young and half transparent leaves scarce cast A shade, gay circles of anemones Danced on their stalks.

Then some lines of Whittier. And finally a bit of flower lore from ancient Greece that will change forever how we perceive the flower when we find it blooming in the sun-dappled shade: In Greek lore the flower sprang from tears shed by Venus over the body of slain Adonis.

Another April blossom, the marsh marigold, is introduced by Mrs. Dana with Shakespeare’s song to “winking Mary-buds” in Cymbeline, which we are assured is the same flower. The “gold” in marigold is easy enough to understand, but whence the “Mari?” Mrs. Dana leads us by the hand at least as far back in this flower’s etymological history as the 16th century without finding a definitive answer. “Marsh-gold” might be a more appropriate name, she decides.

But this handbook is not all just quaint Victorian charm. Mrs. Dana also tells us when to expect the flowers and where to find them. She tells us their Latin names and family, and describes in brief non-technical words the form of stem, leaves, and blossoms. Still, it is the personal, literary touch that makes How to Know the Wild Flowers worth owning a century after it was written.

Natural histories such as this one remind us that it is possible to find, with Shakespeare, “…tongues in trees, books in running brooks, Sermons in stones, and good in everything.”