Originally published 20 November 1995

A few weeks ago [in 1995], the Space Telescope Science Institute released two spectacular pictures of a star-forming region in the constellation Serpens. It was an easy matter to download them quickly over the Internet into my computer.

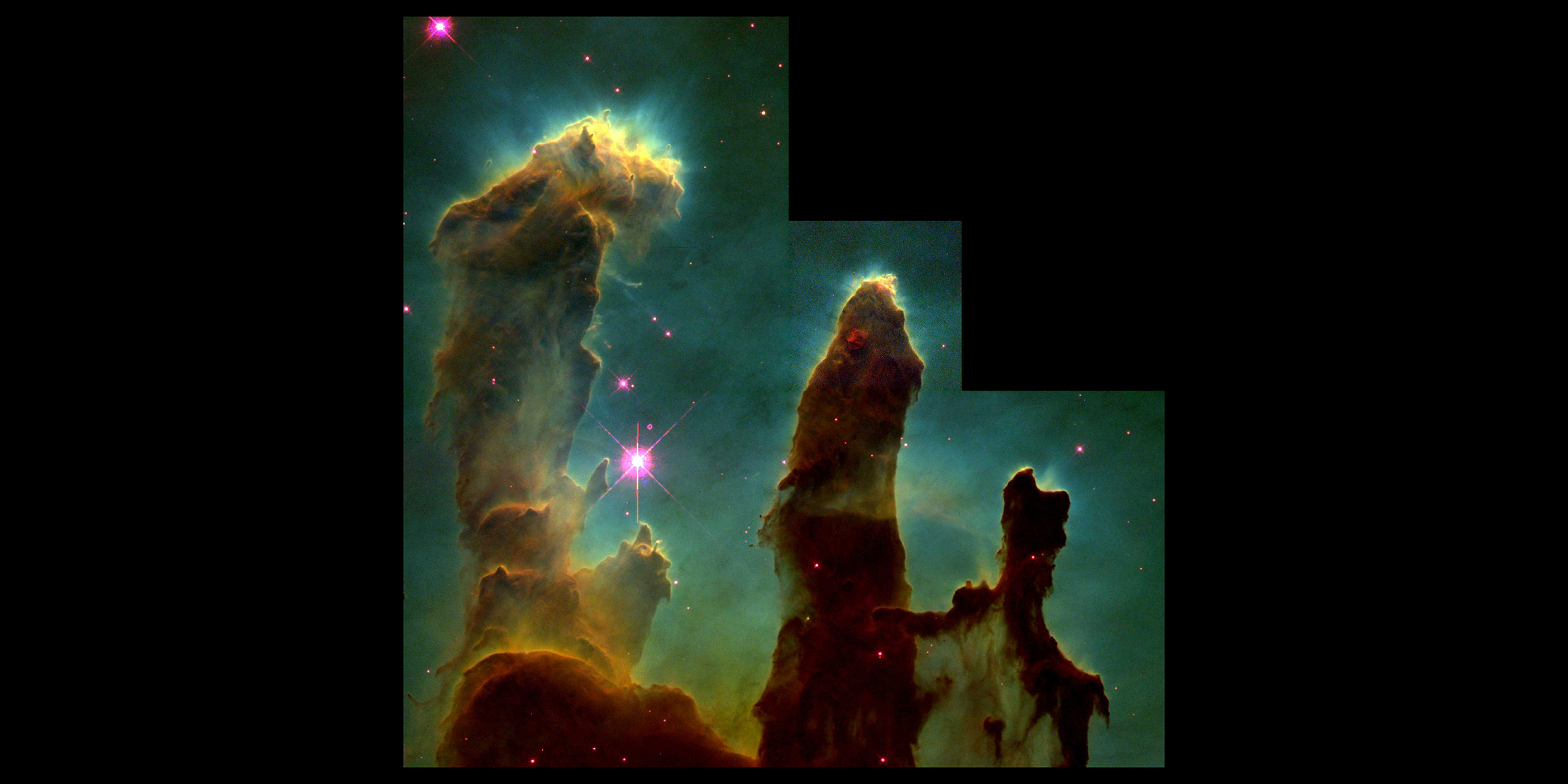

Breathtaking! A luminous nebula, called Eagle, 7000 light-years away and tens of trillions of miles wide. Three tall columns of glowing gas, like an incandescent coral reef. At the top of the tallest column, rays of light stream from the hot interior, blowing away the outer layers of the cloud, except where newly-forming stars, hidden in their swaddling wraps, hold the gas in place. A evaporating stellar nursery, revealing eggs in the nest — new stars, planet systems, worlds.

Of course, we have seen the Eagle Nebula before, particularly in the magnificent photograph made by Ray Sharples with the Anglo-Australian Telescope in Australia, published in David Malin’s A View of the Universe. But the Hubble pictures show fresh details, as if we were seeing the leaves on a tree for the first time. Looking at the new images—the streaming light, the dark globules of condensing stars — is to feel like witnesses to the creation.

The delicately colored photographs were made with three “black and white” exposures, taken in the emission light from three types of atoms: red from singly-ionized sulfur atoms, green from hydrogen, and blue from doubly-ionized oxygen. These newly budding stars are made of familiar elements, and in the same way as our own sun and Earth were created 4.5 billion years ago.

Sitting awestruck before the computer screen, we did not forget that the images were made by a magnificent product of human invention, orbiting the Earth and directed with precision from the ground. We were viewing the images on a high-resolution color monitor connected to the institute by a stream of electronic bits. With the click of a mouse, we were able to plug our imaginations into a stellar nursery many thousands of light-years from home.

A few days later the newspaper reported that when the pictures where shown on CNN, the network was flooded with calls from viewers claiming to have seen the face of Jesus in the billowing clouds. I pulled up the images again and looked carefully, squinting my eyes, turning my head sideways, upside down. I saw what appeared to be the face of a gorilla — King Kong, perhaps — in the tallest column of the nebula. As for Jesus, I couldn’t find him anywhere.

In an article on the psychological basis of belief, the psychologist James Alcock proposed that two aspects of the human brain might be called the “yearning unit” and the “learning unit.” He probably didn’t mean these terms to be taken literally, as referring to separate compartments of the brain, but yearning and learning are certainly central to the way we interact with the world. It is hard to imagine how we can be fully human without a little of each. Finding the proper balance between the two is a task that can keep us occupied for most of our lives.

We yearn when we dream of fulfillment, of greater happiness, of knowing more. We yearn when we love, when we laugh, when we cry, when we pray. Yearning is wondering what is around the next bend, over the rainbow, beyond the horizon. Yearning is curiosity. Yearning is the driving force of science, philosophy, and religion.

Learning is listening to parents, wise men, shamans. Learning is reading, going to school, traveling, doing experiments, being skeptical. Learning is looking behind the curtain for the Wizard of Oz, touching the stove to see if it’s hot, not taking anyone’s word for it. In science, learning means trying as hard to prove that something is wrong as to prove it right, even if that something is a cherished belief.

Yearning without learning is seeing Elvis in a crowd, the fossilized footprints of humans and dinosaurs together in ancient rocks, weeping statues. Yearning without learning is buying tabloid newspapers with headlines announcing “Newborn baby talks of Heaven” and the like. Yearning without learning is looking for UFOs in the sky and the meaning of life in horoscopes.

Learning without yearning is pedantry, scientism, dogmatic belief. Learning without yearning is believing that we know it all, that what we see is what we get, that nothing exists except what can be presently weighed and measured. Learning without yearning is science without a heart, without a dream, without a hope of beauty.

Yearning without learning is seeing the face of Jesus in a gassy nebula. Learning without yearning is seeing only the gas.