Originally published 6 November 2005

My recent Musing about Virginia Woolf’s “moments of being” sparked a thread of comment about those elusive incidents of attentiveness and insight when we are lifted out of the “gray wool” of everyday life and permitted to feel an intense connection with the world beyond our selves. These are the illuminations that Sylvia Plath writes about in “Black Rook in Rainy Weather” that come now and then out of the mute sky, “thus hallowing an interval/ Otherwise inconsequent/ By bestowing largesse, honor,/ One might say love.”

We treasure these moments of being, and seek to increase their prevalence in our lives. The word that seems to have emerged in the comments is “mindfulness.” How do we make our lives more mindful?

The experience of a Virginia Woolf or a Sylvia Plath does not offer much guidance. It seems clear that their particular sensitivity had its origin in a clinically untypical state of mind that led, finally, to despair.

Nor is the Eastern experience of much use to me, a child of Roman Catholicism and Western science. I sought my enlightenment, such as it is, closer to home, in the Western monastic tradition, and the works of the great medieval mystics, such as John of the Cross, Julian of Norwich and Meister Eckhart. Those who have read my book Honey From Stone will recognize these influences on my life. But even as a young man chasing after an unknown God I knew that nature would be an important part of any spirituality I might discover or construct. In this regard — and seemingly paradoxically, since science and spirituality are often seen as poles apart — my science education offered valuable lessons in mindfulness.

There’s a wonderful story the 19th-century paleontologist Nathaniel Southgate Shaler tells in his autobiography about his undergraduate experience at Harvard. His teacher was the great Swiss-American natural historian Louis Agassiz. The newly-matriculated Shaler sat down at his lab bench and Agassiz placed in front of him a tin pan containing a fish. “Study it,” said Agassiz. The boy was not talk to anyone or read anything about fishes until Agassiz gave him permission to do so. “What shall I do,” asked the bewildered student. “Find out what you can without damaging the specimen,” said Agassiz.

In the course of an hour Shaler thought he had seen everything there was to see about the fish, but Agassiz ignored him — for the rest of the day, the next day, and the next. “At first, this neglect was distressing,” writes Shaler; “but…I set my wits to work…and in the course of a hundred hours or so thought I had done much — a hundred times as much as seemed possible at the start. I got interested in finding out how the scales went in series, their shape, the form and placement of the teeth, etc.”

At length, on the seventh day, Agassiz approached the bench and asked, “Well?” For an hour, Shaler disgorged what he had learned, as Agassiz stood puffing his cigar. At the end, the professor departed with a curt, “That is not right.” Shaler went at the task anew, discarding his first notes, and, he tells us, “in another week of ten hours a day labor I had results which astonished myself and satisfied him.”

A good science education teaches one how to pay attention and to see what is there to be seen, rather than what we expect to see. Each of us walks through the world in a wrap of preconceptions and prejudices, some perhaps genetically disposed, others imbibed from family, teachers, and friends. The beginning of a mindful life, it seems to me, is to make one’s self transparent to the world beyond the self — and for this a scientific education is a useful training.

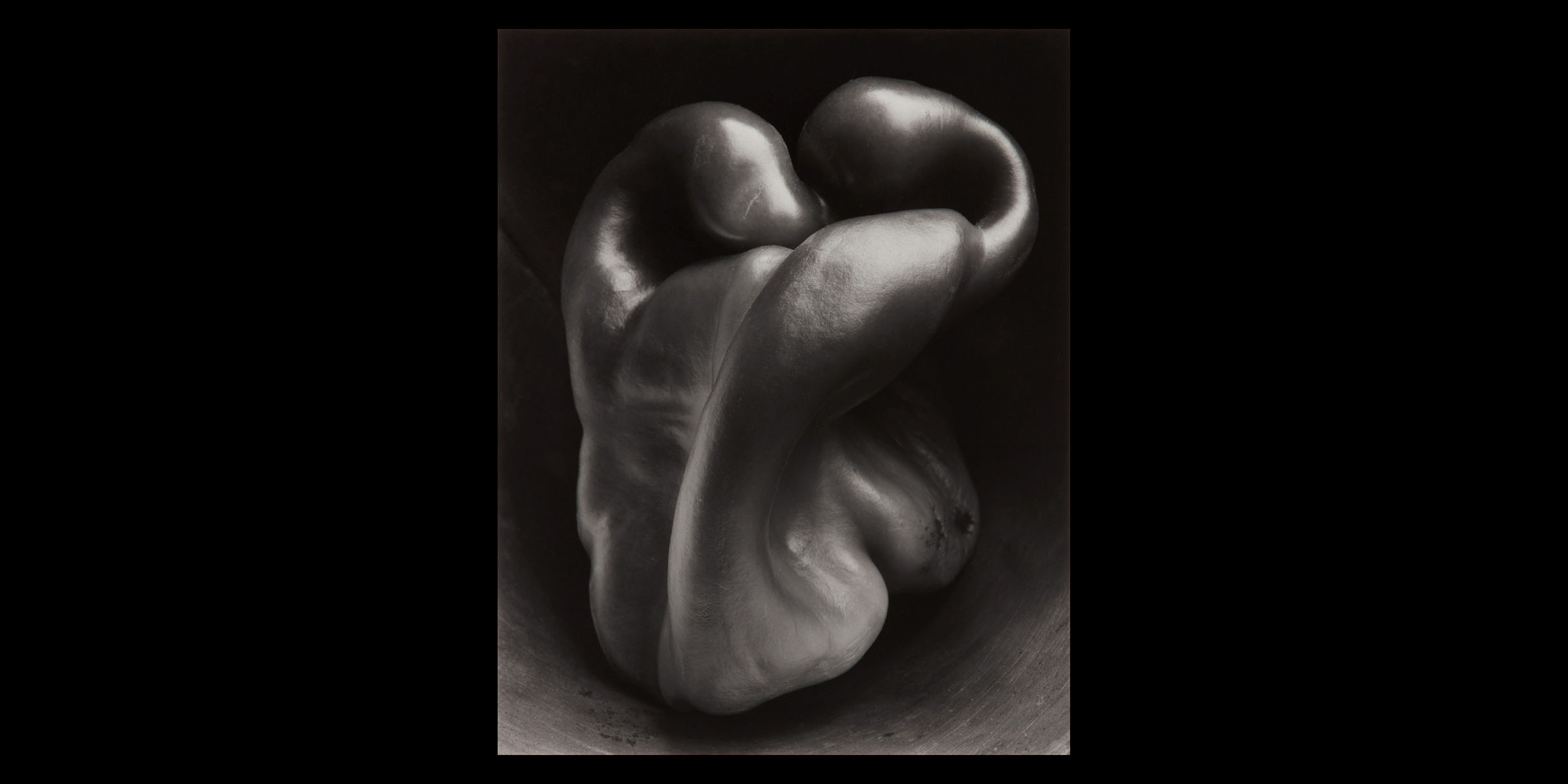

But the artist struggles too to be open to the world, as illustrated, for example, by the “Daybooks” of the photographer Edward Weston, arguably America’s greatest.

Weston was obsessed with recording what he called “the Thing Itself” — clouds, nude bodies, shells, peppers, sand dunes, trees, rocks — seeking what he called the “interdependent, interrelated parts of a whole, which is Life.” He wrote: “I am no longer trying to ‘express myself,’ to impose my own personality on nature, but without prejudice…to see or know things as they are, their very essence.” And again: “I want the greater mystery of things revealed more clearly than the eyes see.”

Weston was skeptical of science, which he imagined to be full of excessive theorizing. Scientists imposed their own ideas on nature, he thought: experimenting, dissecting, confabulating. By contrast, he sought the purity of the unarranged object as he saw it on the glass screen of his camera.

Then, in 1930, a certain Dr. Becking, a scientist, walked into Weston’s studio. Rarely had the photographer found such an understanding response to his work. To Weston’s astonishment, Becking suggested that the photographs represented objects as a scientist might see them — objectively and unadorned.

Later, Weston asked Becking to write the foreword to the catalog of an exhibition. Becking wrote: “Natural science, as an impartial student of forms, cannot but marvel at the rediscovery of fundamental shapes and structures by an artist. Weston has described the ‘skeleton’ materials of our Earth…in a way that is both naive and appealing: in other words, like an inspiring scientific treatise.”

Weston was pleased.

Neither scientists nor artists can ever be truly impartial observers of nature, as Weston eventually came to recognize in his own work. The scientist experiments; the photographer composes. The scientific theory and the photographic print are both artifacts of human creativity, different from the Thing Itself, shaped by social and personal factors.

Still, the ideal of the Thing Itself remained important to Weston, as it is important to every working scientist. Thoughtful scientists know that the world described by science is a social construct, subject to all the foibles of human existence, but nevertheless they hold the conviction — as a kind of religious faith — that the Thing Itself shows itself within their theories.

Like Weston — like all artists and poets — the scientist wants the greater mystery of things revealed more clearly than the eyes can see. And so, as spiritual pilgrims, scientists and artists together, we trek like Plath “stubborn though this season of fatigue,” trying to keep ourselves open to the illuminations that now and then prick the carapace of self, seeking as best we can to “patch together a content of sorts.”