Originally published 1 August 2004

For anyone interested in the history of science, London and its environs are a living museum. Perhaps only ancient Alexandria — the city of Archimedes, Euclid, Aristarchus, Eratosthenes, Hipparchus, and Eudoxos — came near to approaching London as a center of scientific creativity.

No part of London’s scientific history was livelier than the reign of Charles II.

Charles came to the throne in 1660, after England’s troubled experiment with non-royal rule under the violent and puritanical Oliver Cromwell. With the restored monarchy, Londoners enjoyed a gay old debauch, following the example of their fun-loving prince. Drama, arts, and literature flourished. Science too.

Anyone who has studied physics in secondary school or college has heard of Hooke’s Law of Elasticity, Boyle’s Law of Gases, and Newton’s Laws of Motion. Many more people are familiar with Pepys’s Diary and Halley’s Comet. These eponymous gentlemen glittered in the intellectual firmament of late-17th century London, a city with one-fifth the population of present-day Toronto. They knew each other, and fed off one another’s curiosity. Together they established the Royal Society, the first bona fide scientific organization. They can fairly be called the first moderns, and that is exactly what they understood themselves to be.

In 1675, fifteen years into his reign, Charles founded the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Christopher Wren designed the building, with the assistance of Robert Hooke. John Flamsteed was appointed first Astronomer Royal, and it was to Greenwich that Isaac Newton came for observational confirmation of his theory of universal gravitation.

New ideas were in the air, new ways of wresting knowledge from nature. Samuel Pepys, the diarist, was typical of the age. He was a government bureaucrat, not a scientist. Nevertheless he was swept along by the excitement. He purchased every new science book that came off the press and struggled to understand it. He bought a microscope and a telescope and almost every other device that defined the new experimental age. And he cultivated the friendship of scientists. In 1665 he was elected to membership in the Royal Society; later, he became its president.

A new age was being born, defined by a conviction that the world is ruled by natural laws that can be discovered by human reason. But the old ways lingered. One moment Pepys might be observing an experiment on blood transfusion, and the next he is at Charing Cross to see some perceived enemy of the realm drawn and quartered as a kind of spectator sport. One moment he listens to Robert Hooke speculate that comets are periodic objects that obey exact mechanical laws, and the next he worries that the year 1666 is characterized by “666,” the number of the Beast of the Apocalypse.

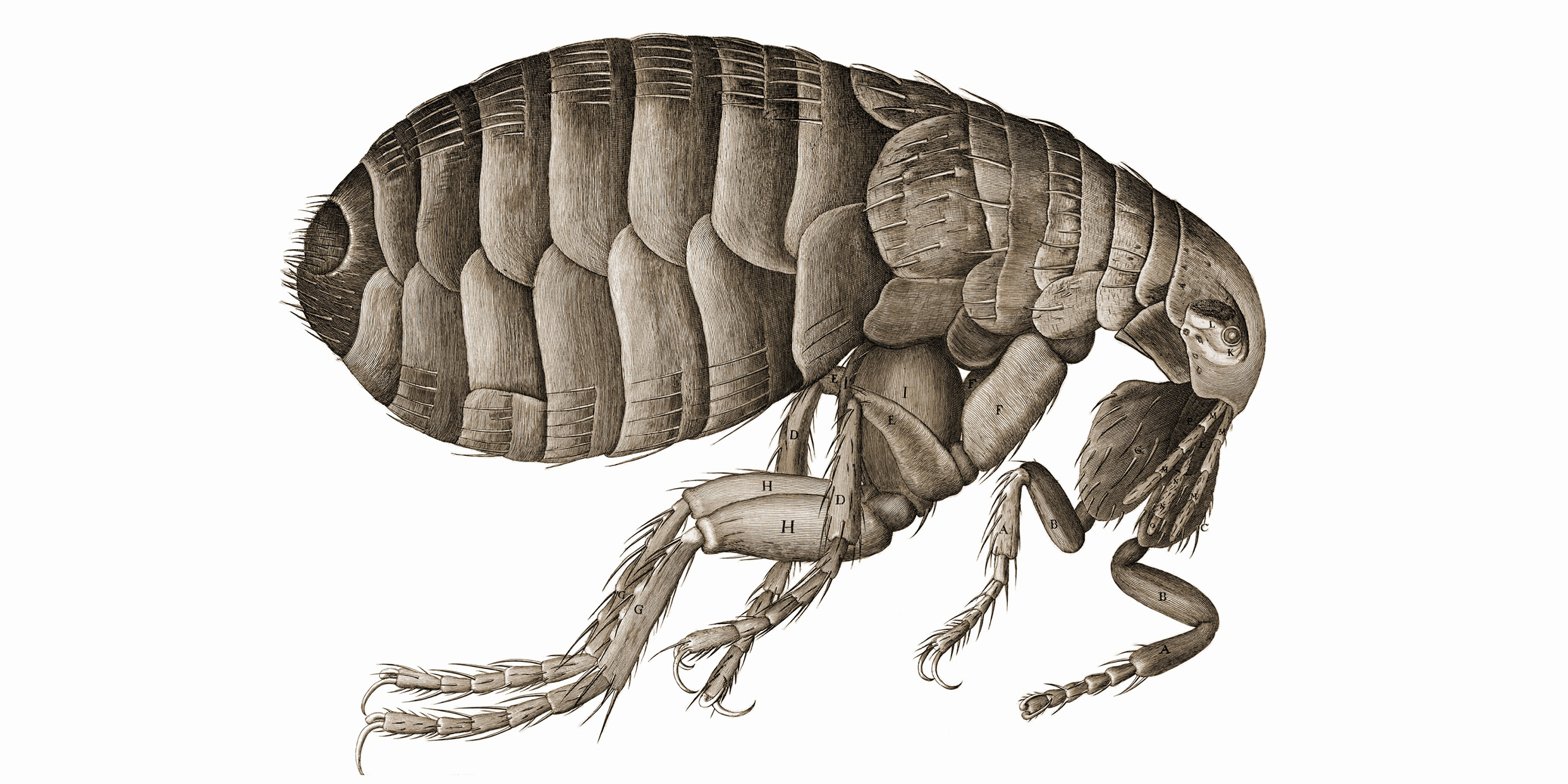

In his diary entry for January 21, 1665, Pepys attributes his good health to the influence of his new rabbit’s foot, a lucky charm. Then he sits up late reading Hooke’s Micrographia, a book that records some of the first scientific observations with a microscope. Among the famous illustrations in that book is one of a flea, sketched by Hooke with every bristle, crease and scale, and published in the very year that plague ravaged London, killing thousands and virtually shutting down the city. We now know that the disease is caused by flea-borne bacteria.

We no longer participate in public executions, carry rabbit’s feet, worry about apocalypse, fear comets, or die of plague. Or at least most of us don’t in the developed western world, where, since the late-17th century, science has held sway. And the reason, of course, is reason—as embodied in the scientific way of knowing created by the virtuosos and savants of the Royal Society.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that modern science got its institutional start during the reign of the debauched Charles II. For all of his sorry human failings, the monarch encouraged religious tolerance, artistic vivacity, and intellectual freedom. If history is a guide, science thrives best in societies that are secular, democratic and free.