Originally published 13 February 1989

Previously, in a column on the scientific reputation of Benjamin Franklin, I mentioned Willard Gibbs, calling him the greatest scientist America produced until our own century. Several readers asked, “Who’s this guy Gibbs you think so much of?” An informal survey confirmed Gibbs’ anonymity; no one I questioned could place the man or his achievements.

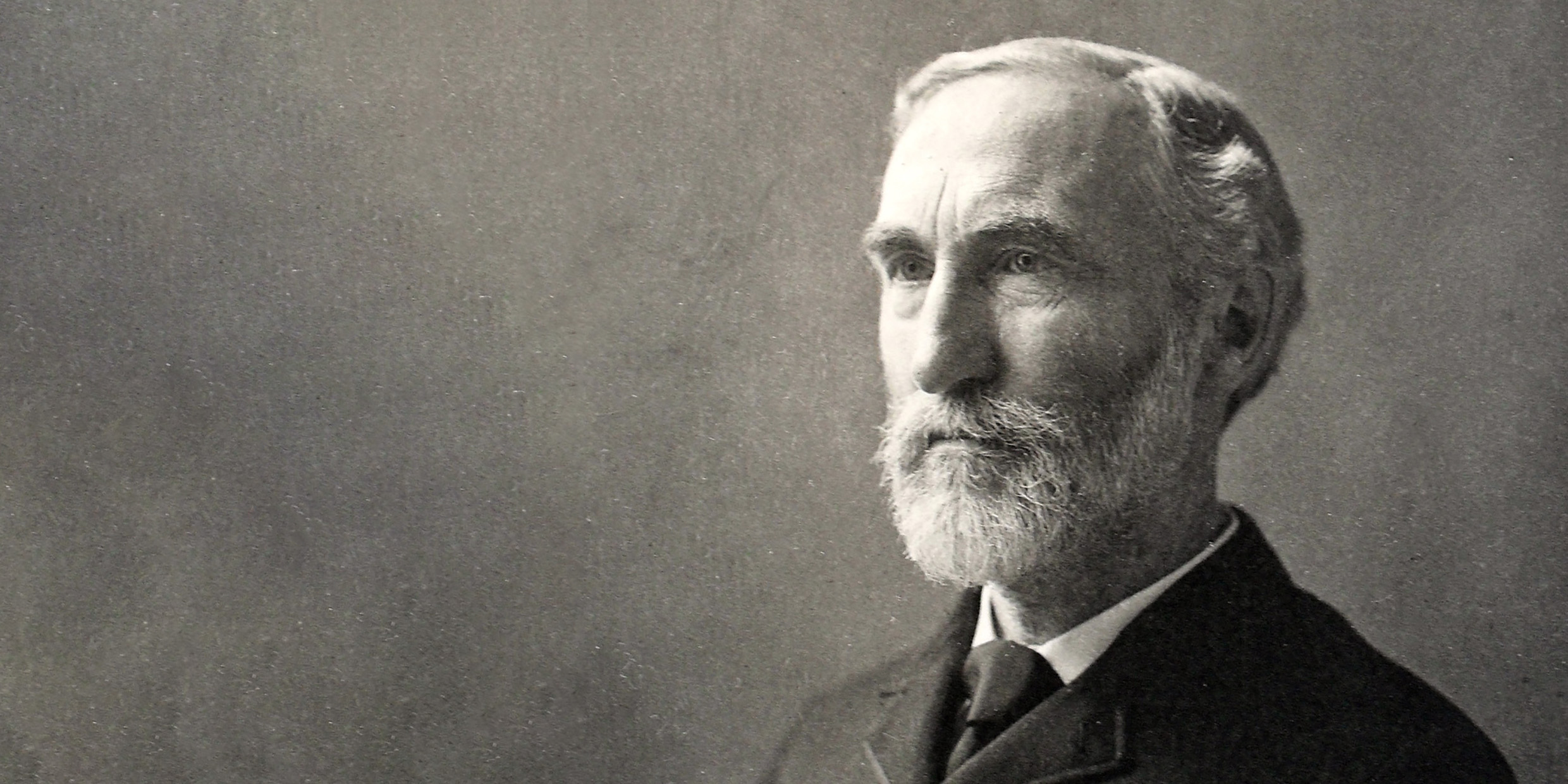

Now it turns out we have just celebrated [in 1989] the 150th anniversary of the birth of Josiah Willard Gibbs—on February 11, 1839 in New Haven, Connecticut — so perhaps this is an appropriate time to rescue the great New England scientist from undeserved obscurity.

I am not alone in my estimate of Gibbs’ importance. There are those who would say Willard Gibbs is the greatest American scientist of all time — including our own century. Toward the end of his life, Albert Einstein was asked who he considered the most powerful thinker he had ever met. He answered without hesitation, “Lorentz,” referring to Hendrick A. Lorentz, the Dutch mathematical physicist, and then added — “I never met Willard Gibbs; perhaps had I done so, I might have placed him beside Lorentz.” High praise indeed from the towering scientific genius of the 20th century.

Years ago, as a graduate student in physics, I kept coming across Gibbs’ name — Gibbs’ phase rule, Gibbs’ paradox, Gibbs free energy, the Gibbs-Helmoltz equation, Gibbs functions, Gibbs ensembles, and so on. The name popped up in texts on chemistry, mathematics, theoretical mechanics, optics, and thermodynamics. Sometimes the latter subject seemed entirely a Gibbsian invention.

Never in the public eye

Who was this fellow who was so prolific in shaping so many branches of science? Physicists and chemists acquainted with Gibbs’ scientific achievements knew little of the man. Non-scientists did not even recognize the name.

I tracked down Lynde Phelps Wheeler’s biography of Gibbs and the first paragraph held the key to his obscurity: “The outward life of Josiah Willard Gibbs was singularly uneventful. He experienced no adventures different from those common to thousands of Americans of his time. He was a participant in no events of historical importance. He took no leading part in any of the movements of the age. He traveled less, and lived at home more than the great majority of people of similar means. He neither sought nor occupied positions of influence in his own scientific world. He was never in the public eye.”

With such a beginning, one may wonder what attracted the biographer to his subject. But the history of civilization is not only written on battlefields and in corridors of power. It is written also in the imagination of men such as Gibbs, who sought and found fundamental principles of physical chemistry and thermodynamics, and who perfected mathematical tools for the exercise of science. Wrote Wheeler: “He explored the far horizons of the hitherto unknown…and mapped a major scientific continent.”

Gibbs lived in an age of mechanical invention and the raw aggrandizement of power — the age of the transcontinental railroad, the Atlantic cable, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the efficient killing technologies of Shiloh and Gettysburg. His own city of New Haven boasted of Charles Goodyear, discoverer of the vulcanization of rubber, Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin and manufacture by interchangeable parts, and Samuel Morse, inventor of the electrical telegraph.

In such a world the abstractions of Willard Gibbs found few admirers. His elegant formulas and equations, couched in mysterious Greek symbols, held little interest for his practical-minded countrymen.

Not that Gibbs’ theories were without practical application. Almost every branch of technology ultimately benefited from his work, especially the chemical industry. Alloys, explosives, fuels, and medicines were all touched by his genius.

Lived most of life in New Haven

But down-to-earth applications do not seem to have concerned the gentle scholar of New Haven. Except for three years of study in Europe, Gibbs lived all his life in that city, as a bachelor in the home of his sister. He plied his duties as professor at Yale University with quiet dedication, avoiding the spirited debates of university politics. He is remembered at Yale for uncharacteristically standing up at a faculty meeting and saying, to everyone’s astonishment in the midst of a curriculum debate, “Mathematics is a language.”

As his work became known, universities here and abroad bestowed upon him honorary degrees. He was recipient of the Rumford Medal of the American Academy of Sciences and the Copley Medal of London’s Royal Society, the highest honor open to a scientist until the founding of the Nobel Prize. So modestly did Gibbs absorb these accolades that even his friends were unaware of the honors until they read of them in his obituary.

Gibbs’ physics was one great cornerstone of 19th century science that survived unscathed the intellectual revolutions of the 20th century. He died in 1903, just two years before Einstein and Max Planck published their epoch-making papers on relativity and quantum physics. These two founders of modern physics were late to discover the works of Gibbs, and consequently, reinvented many of the same results — with difficulty. Einstein knew of what he spoke when he placed Gibbs in the highest rank of genius.