Originally published 25 October 1993

On a cold night in April 1928, Stalin’s secret police knocked on the door of Peter Palchinsky’s Leningrad apartment.

Palchinsky was an engineer, one of the most influential and talented in Russia. For 30 years he had worked as an engineering consultant, first for the Czarist government, then for the Bolsheviks. He believed that industrialization should proceed so as to increase the happiness and prosperity of the people. A happy, motivated work force would in turn increase the efficiency of production.

Socialist Russia had the opportunity to develop a far more humane industry than anywhere else, thought Palchinsky. He admired American workers, but thought capitalist managers in the United States were too narrowly interested in profit.

His belief that efficiency must always be linked to justice finally brought him afoul of Stalin, who stressed that “technology decides everything.” The police led him away. He was convicted without trial for treason, and executed by firing squad.

Palchinsky’s story is told in a new book by MIT historian Loren Graham: The Ghost of the Executed Engineer: Technology and the Fall of the Soviet Union. It’s a terrific read, and a needful reminder of what happens when technology is loosed from social responsibility.

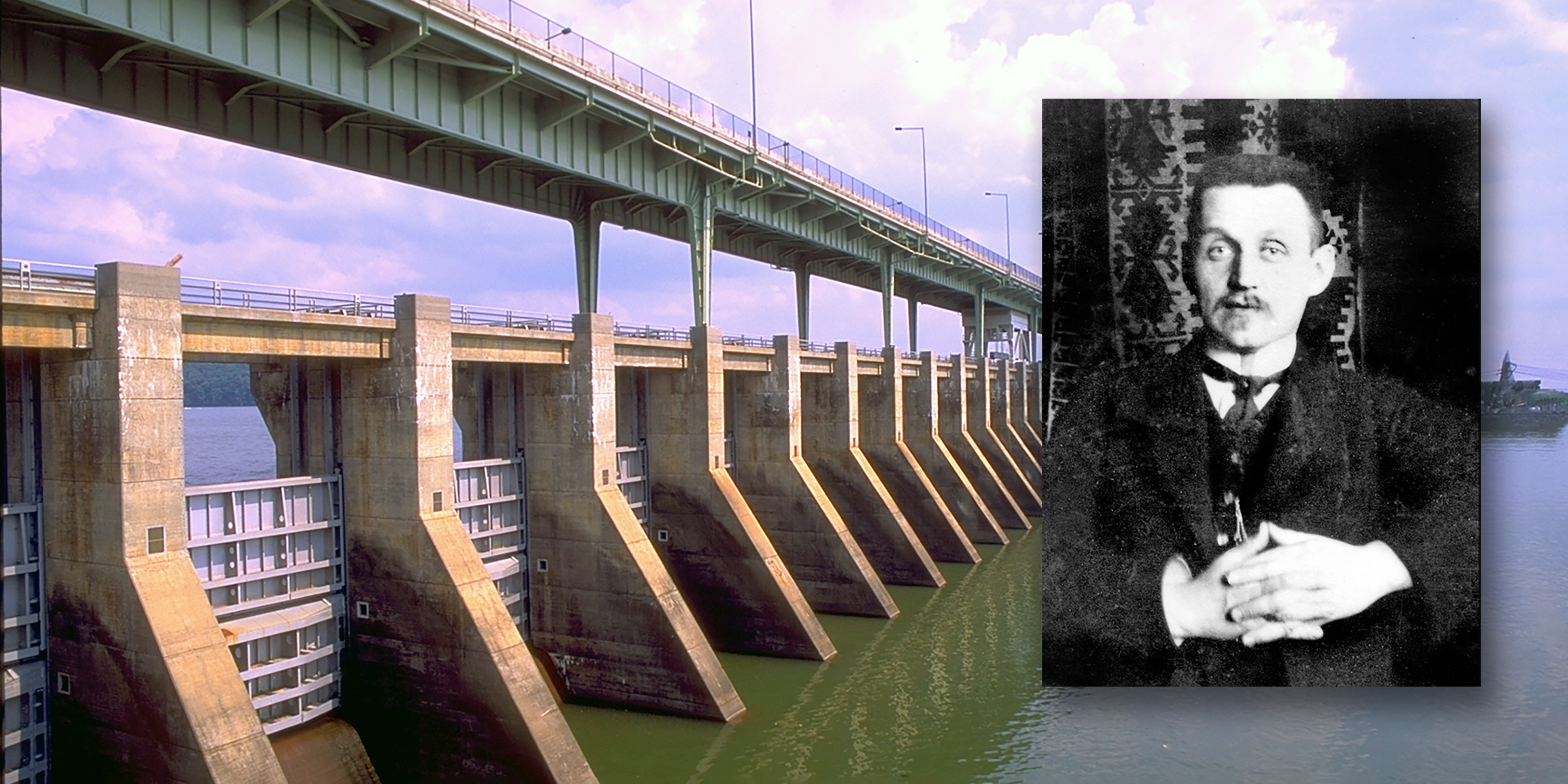

Graham writes of the megaprojects that defined Soviet might in the late-20s and 30s — the Dneprostroi hydroelectric dam on the Dnieper River, the steel-producing city at Magnitogorsk, the White Sea Canal — carried forward by Stalin and his henchmen without proper planning, with forced or propagandized labor, and against the advice of Palchinsky and other technical specialists. Graham believes these ill-conceived and inhumane projects held the seeds of the future disaster at Chernobyl and collapse of the Soviet economy.

Stalin’s demand for industrialization at whatever human cost stands as one of the great social crimes of our century. But it would be a mistake to believe that technology can not run amok in less grotesque ways. The steel-producing cities of Magnitogorsk and Gary, Indiana, are both are plagued with poverty, unemployment, drugs or alcohol, and urban blight.

As multitudes of slave laborers and volunteer “enthusiasts” were building the Dneprostroi Dam, the blast furnaces at Magnitogorsk, and the White Sea Canal, the US Congress passed landmark legislation that engaged our government in a regional development program of similar size and scope: the Tennessee Valley Authority Act.

I was a child of the TVA, born into the valley of the Tennessee River as the first dams neared completion. Chickamauga Dam near Chattanooga was a constant presence in my childhood, first as a wonder of engineering, then as a source of esthetic pleasure and recreation. My father was an engineer whose employers prospered on cheap TVA electricity. During the summer between my freshman and sophomore years of college, I worked for the TVA.

The TVA Act of 1933 called for flood control, improvement of navigation, generation of electric power, land reclamation, reforestation, and — most significantly — the economic and social well-being of the people living in the Tennessee River basin.

As the dams and reservoirs were built, the Authority was mindful of human details. Families displaced by reservoirs from rich bottomlands were helped to actually increase their productivity on new upland farms. Rural homes, not just factories, were speedily electrified. Even cemeteries to be submerged by rising waters were carefully moved to new sites chosen by churches and communities.

One can argue that the government had no business doing what might have been accomplished by private enterprise; that TVA dams permanently flooded more land than they were meant to protect from floods; that rivers are meant to run free; that the entire nation unfairly subsidized cheap power in the Tennessee Valley; and so on. But I know from having been there that this mammoth undertaking was popular with the people that it served, and that it transformed the economic and social fabric of the region in countless beneficial ways.

Development in the Tennessee Valley during the 30s and 40s stands in stark contrast to the wretched excesses of Soviet engineering described by Graham. The TVA was precisely the sort of centrally-planned, semi-socialist, regional undertaking advocated by Palchinsky. It was based on systemic, scientific principles. The valley continues to prosper today, whereas the Soviet industrial machine has ground to a halt.

Not long ago, Václav Havel the playwright and president of independent Czechoslovakia, wrote that the fall of communism marked the end of an era based on scientific objectivity. Against these excesses of “arrogant, absolutist reason,” he urged us to embrace our own subjectivity as our link with the subjectivity of the world. His profoundly anti-scientific stance has found wide approval among intellectuals.

Havel got it exactly backwards. The industrialization of the Soviet Union was neither scientific nor objective. The brightest Russian advocate of scientific objectivity was dragged away in the night and placed before a firing squad.

According to Graham, it is probable that Peter Palchinsky’s execution resulted from his refusal, even under torture, to confess to crimes he did not commit. Palchinsky prided himself on being a rational, scientific engineer, within a system that was anything but rational or scientific. His integrity cost him his life.