Originally published 18 July 2000

We thrilled to the recent photographs from Mars showing what appear to be relatively recent water channels on the red planet.

The Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft has been circling Mars for more than a year, mapping the surface. Pictures from the Gorgonum Chaos region and other locations “suggest the presence of sources of liquid water at shallow depths beneath the Martian surface,” NASA scientists Michael Malin and Kenneth Edgett wrote in Science magazine.

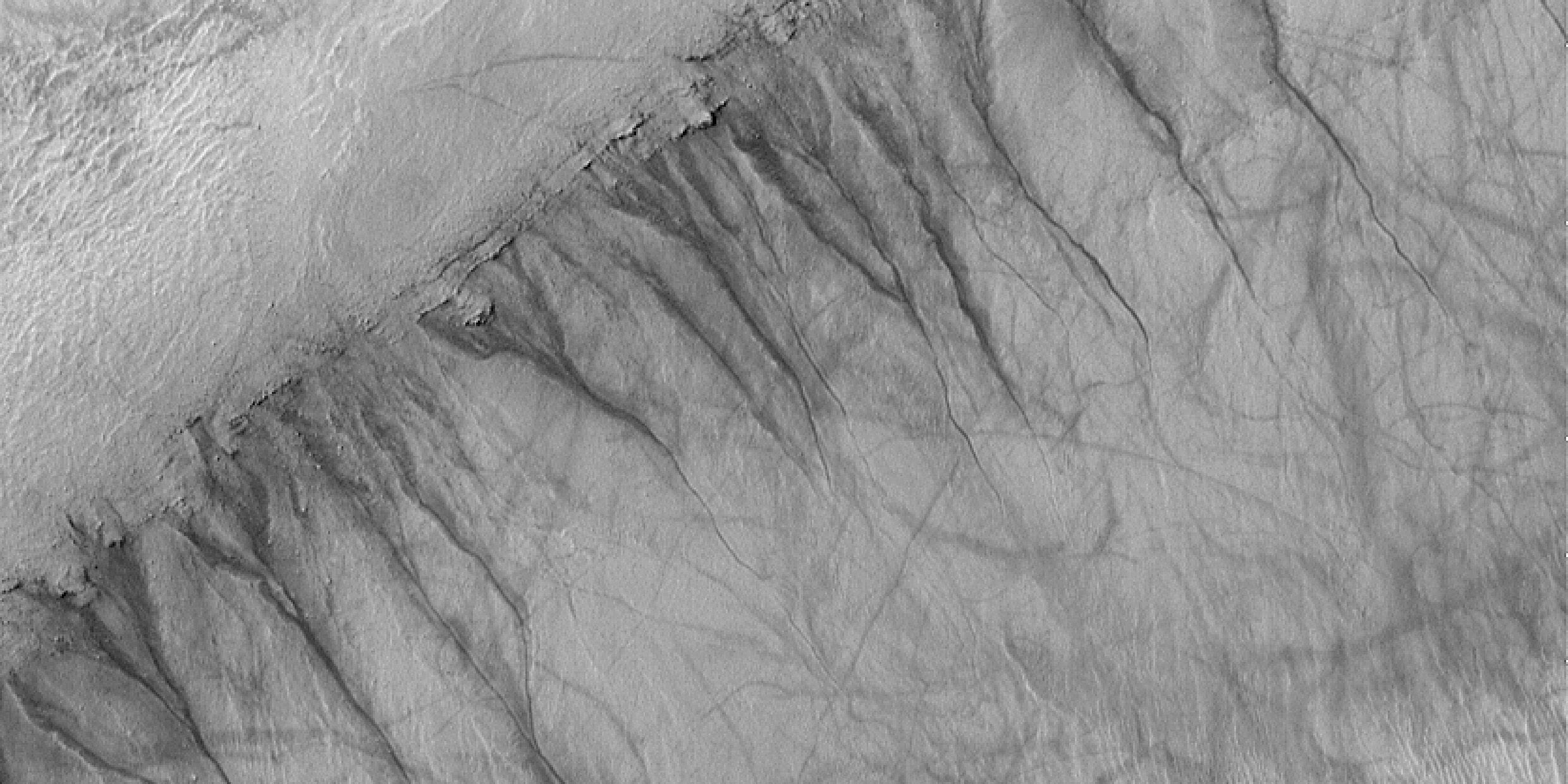

Of particular beauty are photographs of a crater wall that seem to show unmistakable rills and gullies carved by water flowing into the crater’s bowl from sources under the rim.

Malin and Edgett think they have seen signs of ground-water seepage and surface runoff at hundreds of locations on Mars. The gullies are apparently dry now, although the absence of superimposed impact craters or windblown dunes suggests they are relatively young.

Readily accessible liquid water on Mars immediately enhances the possibility that microbial life might exist there, and makes human travel to the red planet all the more attractive.

There’s another story behind the photographs of the presumed water channels, and that’s the story of the pictures themselves — not what they show but that they exist at all. Exploration of the solar system has become so commonplace that we sometimes forget the astonishing technology behind the news. A photograph from Mars seems no more remarkable than a photograph from Australia or Timbuktu.

But Mars at its closest is 12,000 times farther away than Timbuktu. What is usually missing in accounts of solar-system explorations is a sense of scale.

When Mars Global Surveyor was launched in November 1996, Mars and Earth were on the same side of the sun, but Earth was lagging behind Mars in their orbits. The spacecraft required 10 months to cross the gap between the planets, on a long sweeping arc that chased Mars halfway around its orbit. Meanwhile, Earth lapped Mars and moved ahead.

When the craft reached Mars, it went into an elliptical orbit that took it far out from the planet, then in close to dip into the Martian atmosphere. By using the drag of the atmosphere to slow the spacecraft down — a technique called aerobraking — NASA saved fuel, weight, and expense on the journey.

In March 1999, the Mars Global Surveyor was finally in a low circular orbit and began mapping the surface. In April 1999, Earth again caught up with Mars and raced ahead. Now, in the summer of 2000, the planets are on opposite sides of the sun.

During all of this time — during all of this whirling of the planets in their orbits and on their axes — NASA has been in communication with the spacecraft.

Think of the Earth as a grapefruit. On this same scale, Mars is a lemon. As I write, I am looking out the window of a house on a hillside in the west of Ireland, across a mile of fields to the parish church, which is just about the right size and distance to be the sun on this same scale.

I try to imagine a submicroscopically small spacecraft hurled off a grapefruit in my hand, traveling on an expanding arc out across the parish, and meeting the lemon a mile and a half on the other side of the church, way out there over Dingle Bay.

In our world, the Mars Global Surveyor is about the size of the family van, with two huge solar-panel wings that catch the sunlight. In my scaled-down solar system, spread out across the parish, the spaceship is the size of an atom, now circling a lemon 2½ miles away, sending back pictures of every bump and rill on Mars.

Meanwhile, here on the grapefruit, dish antennas track the spacecraft, receiving streams of data, and sending signals that tell the craft what to do — when and how to fire its thrusters, where to point the cameras. Computers hum, churning out the hugely complicated calculations that make it all possible.

We take it for granted, but as I sit here looking out the window, trying to fix the scale of things in my mind’s eye, I marvel at the extraordinariness of the achievement. Here is the photograph of the crater wall — the golden red dust of Mars — with those twisting gullies winding down into the bowl. Pixel by pixel, this remarkable document was transmitted from “way over there” to “way over here” on ethereal waves that winged through empty space.

Someday, humans will cross those vast distances. When they do, they will count on finding the water that appears to be hiding under the Martian surface, to sustain their life, perhaps even to make the fuel that will see them home.