Originally published 23 June 1997

What’s a billion?

15 billion is the age of the universe in years.

10 billion is the distance to the farthest visible galaxies in light-years.

10 billion is the number of galaxies potentially visible to the Hubble Space Telescope.

4 billion is the age of life on Earth in years.

1 billion is the distance to Saturn in miles.

1 billion is the number of creatures in 1 acre of rain forest.

2 billion is the number of nucleotide pairs (the basic unit of the genetic code) in human DNA.

100 billion is the number of neuron cells in the human brain.

6 billion is the number of human beings on the planet.

1 billion is the number of bytes (alphanumeric characters) of information that can be stored on the hard disk of my laptop computer.

It seems like almost everything we talk about in science today is expressed in billions. The human mind reels before such numbers.

What does it mean to live in a universe of 10 billion galaxies, each of which contains 100s of billions of stars?

What does it mean to live in a universe that is billions of light-years wide (at least), each light-year equal to 1,000s of billions of miles?

What does it mean to be part of a history that is billions of years long, against which the duration of a human life is like a snap of the fingers?

What does it mean to say that each of the 1,000s of billions of cells in our bodies contains a complete DNA blueprint for making a physical self, each of which contains billions of chemical units that must be reproduced exactly each time the cell divides?

How are we supposed to feel at home in a universe that soars in its multitudes beyond the powers of our reckoning?

Science has unraveled a stupendous story of creation, sweeping in its grandeur, myriad in its dimensions, and we can only shake our heads in incomprehension.

No wonder so many of us retreat into the cozy, egg-like world of our ancestors, thousands of miles wide, thousands of years old.

What exactly is a billion?

If you started counting at birth, and counted day and night, unceasingly, you could just about count to a billion in a human lifetime. It would take 10 lifetimes to count the visible galaxies in the sky.

A billion is the number of grains of salt in two dozen one-pound boxes of salt. There are more stars in the Milky Way Galaxy than there are grains in 10,000 boxes of salt.

A billion is the number of letters in five sets of the 32-volume Encyclopædia Britannica. It would take 23 sets of the Britannica to have a letter for each year of Earth’s history (the span of a typical human life is the last line of the last volume). It would take 10 sets of the Britannica to contain the information in human DNA.

OK, we can rattle off analogies, but big numbers still make us dizzy.

We still recoil in terror from the yawning multitudes.

How does one learn to live — comfortably, happily — in a universe of billions?

For one thing, we can start young. A child’s mind is wonderfully elastic. Those children who have been exposed to big numbers at a young age come into my astronomy and Earth history classes with stretched imaginations. Trekkies and dinosaur buffs take to the billions like ducks to water.

Computers help. Six-year-olds these days talk knowingly of gigabytes (billions of bytes). If they haven’t got a gigabyte of hard drive on their computer, they might as well kiss the best computer games goodbye. Computers are breeding a new gigageneration.

Meanwhile, the rest of us struggle to feel at home in the giga-universe.

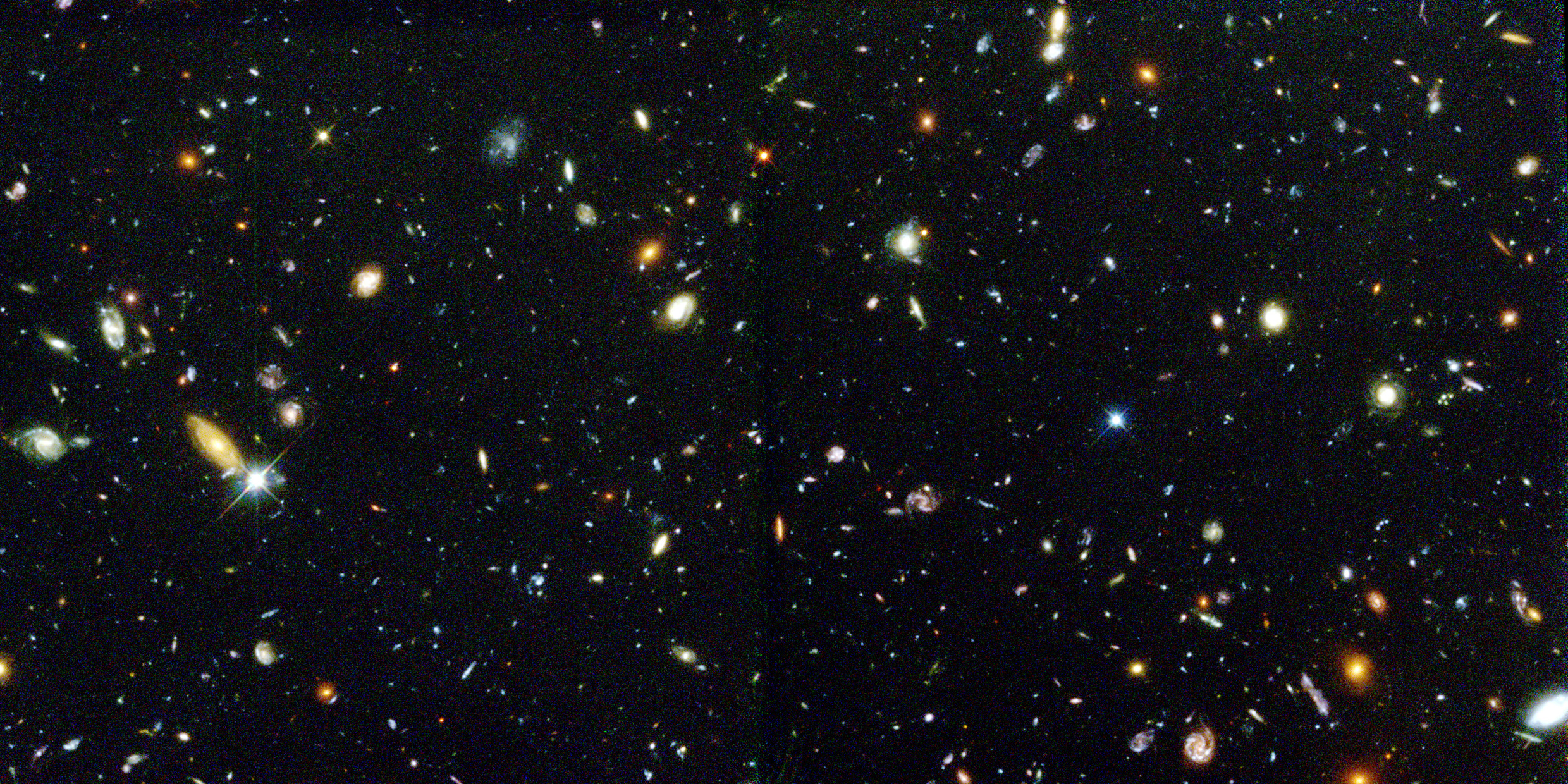

My son installed the Hubble Deep Field photograph as the desktop pattern on my laptop computer. The photo, in living color, is the deepest view we have ever had into space. It shows a part of sky equal to the intersection of crossed straight pins held at arm’s length. The shutter of the camera was open for a total of 10 days. Nearly 2,000 galaxies are visible in the photo. The most distant galaxy in the photograph is about 10 billion light-years away.

The Hubble image is before me as I work, filling the margins of my screen around the edges of my documents, intruding its infinitude into my imagination.

Each of the tiny whirling spirals on the photograph is a multitude of stars and planets. Billions, and billions, and billions…