Originally published 31 January 1994

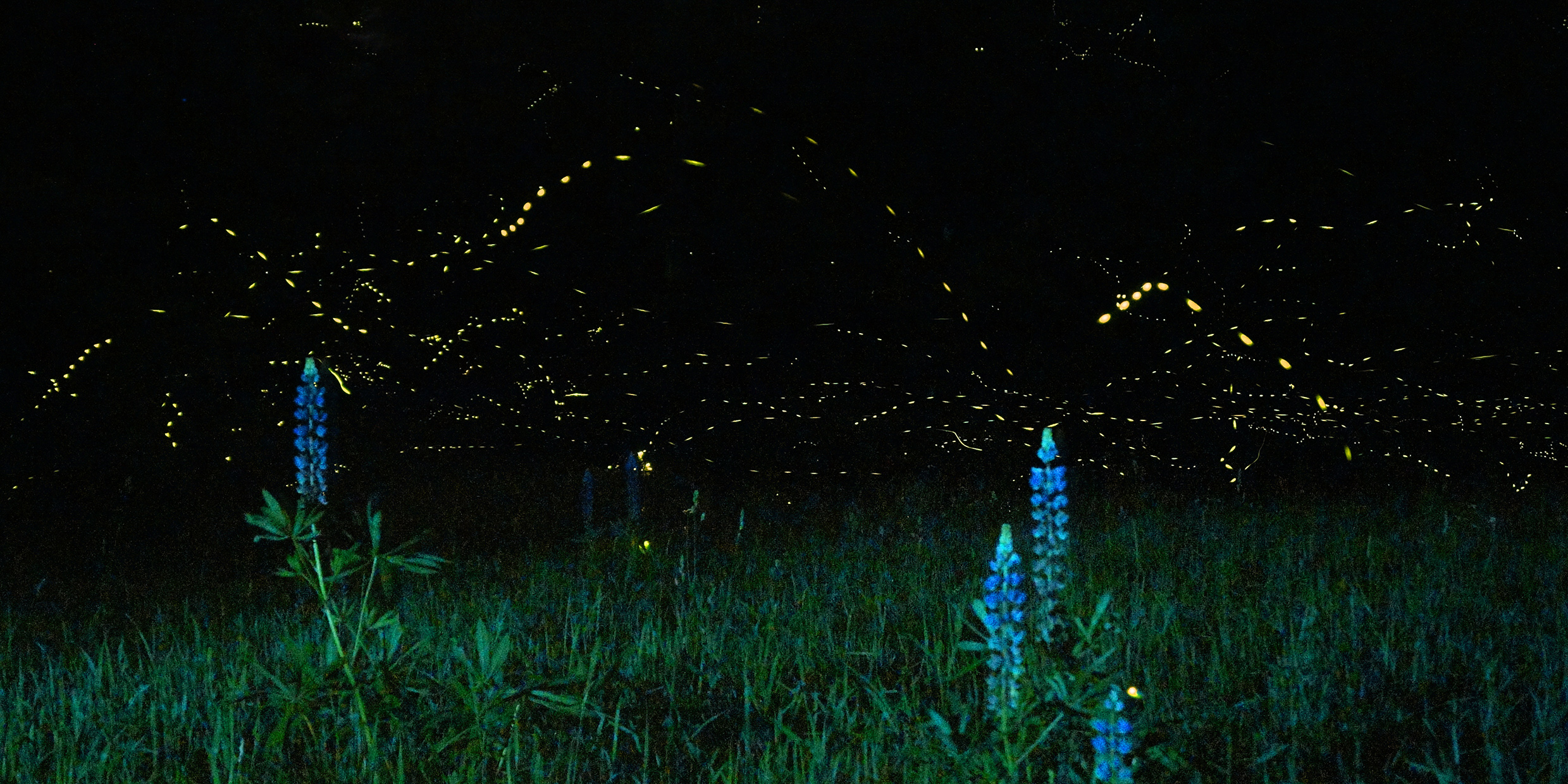

Along the tidal rivers of Southeast Asia, thousands of male fireflies gather in trees at dusk and flash their bioluminescent lights in an attempt to attract the female of the species. At first, their blinking is uncoordinated, but as darkness deepens they begin to flash in unison. Soon, entire trees full of fireflies pulse like flickering fires.

The females, from far off, see the pulsating lights. They come. They mate in the cold incandescence of a winking tree.

As the glowworm love song says, when you gotta glow, you gotta glow. Everywhere, from the riverbanks of Southeast Asia to the inky depths of the oceans, nature glows with self-lit lights.

Certain toadstools can be seen from far off by their own shining. The lips of the megamouth shark are lined with hundreds of tiny lights that twinkle like a fairground’s string of bulbs, enticing plankton into the gaping maw. Some starfish, if threatened, shed a glowing arm to distract the attacker, then flee in darkness to grow another.

Not so long ago, scientists believed self-luminescence was rare in nature. Now we know that living lights are common, especially in the sea. In very deep water, perhaps as many as 90 percent of creatures are luminescent.

The female marine fireworm releases her eggs in a luminous secretion for the male to find and fertilize.

The angler fish of the dark abyss dangles a lighted wormlike appendage in front of its mouth and waits for an unwary prey to take the bait.

Certain species of surface-swimming squids emit light from their undersides that mimics sky-glow, the better to hide from predators below.

Sex, predation, defense: The uses of light by living organisms are wonderfully diverse.

Behind them all is a bit a basic chemistry. Proteins combine with oxygen to jack up the energy of molecules; when the molecules return to their original lower energy, they emit photons of light. The process is facilitated by an enzyme called luciferase. It is luciferase that makes the glowworm glow.

Recently, biologists have begun harnessing the firefly’s blinking tail light to make things glow that never glowed before.

Eight years ago, a group of geneticists in California isolated the firefly’s luciferase gene, the DNA segment that gives rise to the firefly’s light-producing chemistry. They transferred the gene into the cells of tobacco plants, creating plants that glow an eerie green.

More recently, firefly genes have been introduced into the arteries of dogs, making the pooches shine with an inner light.

Researchers have also isolated light-producing genes from a Jamaican beetle called the kittyboo. Kittyboo genes give expression to four colors of light, and these have been introduced into yet other organisms. Scientists are learning how to make plants and animals glow with a rainbow of hues.

There is a serious purpose behind this research. In many experiments, the luciferase gene plays the role of a tag or marker that can be detected by the luminescence it stimulates. For example, chemicals from a firefly’s tail can be added to the urine sample of a patient who may be suffering from bacterial infection. If bacteria are present in the urine, the firefly extract will make them glow with a faint but detectable light.

The lights of the firefly and kittyboo are also being used to study gene expression, monitor plant diseases, track the spread of toxins in the environment and detect cancerous tissue.

One can imagine more frivolous uses.

Light is the ultimate aphrodisiac.

Where geneticists lead, the commerce of sex will follow. Think of it. Lovers glowing in the darkness with the glowworm’s come-hither light, like a luminous perfume. I can foresee the ads in GQ and Vogue: Bioluminescence genes by Mennen and Clinique. Let Estée Lauder make you glow with love’s soft light.

Once the luciferase gene is in the body, the light will be turned on and off according to the demands of romance, perhaps by drinking a concoction of appropriate chemicals to catalyze the reaction, or perhaps a way can be found to initiate the reaction with the hormonal secretions of sex. Lovers will ignite with the kittyboo glow of desire. Their eyes will shine with the firefly’s love-light.

Fantasy? Don’t bet on it. The genetically-engineered 21st century will hold bigger surprises than this. Candlelight, moonglow, and starlight have always evoked the expression of passion. In 30 years or so, bioluminescent lovemaking will be all the rage.

The old song had it right. The glowworm will lead us on to love.