Originally published 17 May 1993

Quick. Give a brief definition of PCR (polymerase chain reaction).

Now do the same for ESP (extrasensory perception).

What can you say about SETI (search for extraterrestrial intelligence)?

How about Yeti (“Bigfoot”)?

What is the SSC (superconducting supercollider)?

What is a UFO (unidentified flying object)?

A few weeks ago I visited one of Boston’s best high schools for a dialogue with students. I began the discussion by listing 20 terms on a blackboard — the six above and the following: parallel processing, hot (and cold) fusion, reincarnation, Loch Ness Monster, COBE (Cosmic Background Explorer satellite), Shroud of Turin, fractals, close encounters of the third kind, the Genome Project, the Bermuda Triangle, Adam and Eve, superconductivity, scanning tunneling microscope, and horoscope.

I went through the list one by one, asking for a show of hands on the following question: “For which topics could you give a reasonably confident explanation?”

You can guess the outcome. For half of the topics, only a few hands went up. For the other half, most hands in the room were raised. I’m sure you can guess which topics fell into each category.

Half of the topics are drawn from cutting-edge contemporary science. They refer to important developments that have the potential to profoundly change the way we live our lives or the way we understand our world.

The other half refer to things which the scientific community would say have no literal truth value.

I have no doubt that the exercise would have produced the same result with a typical nonscience class at Harvard, or almost any other audience. We are, it would seem, vastly less knowledgeable about science than about pseudoscience and superstition.

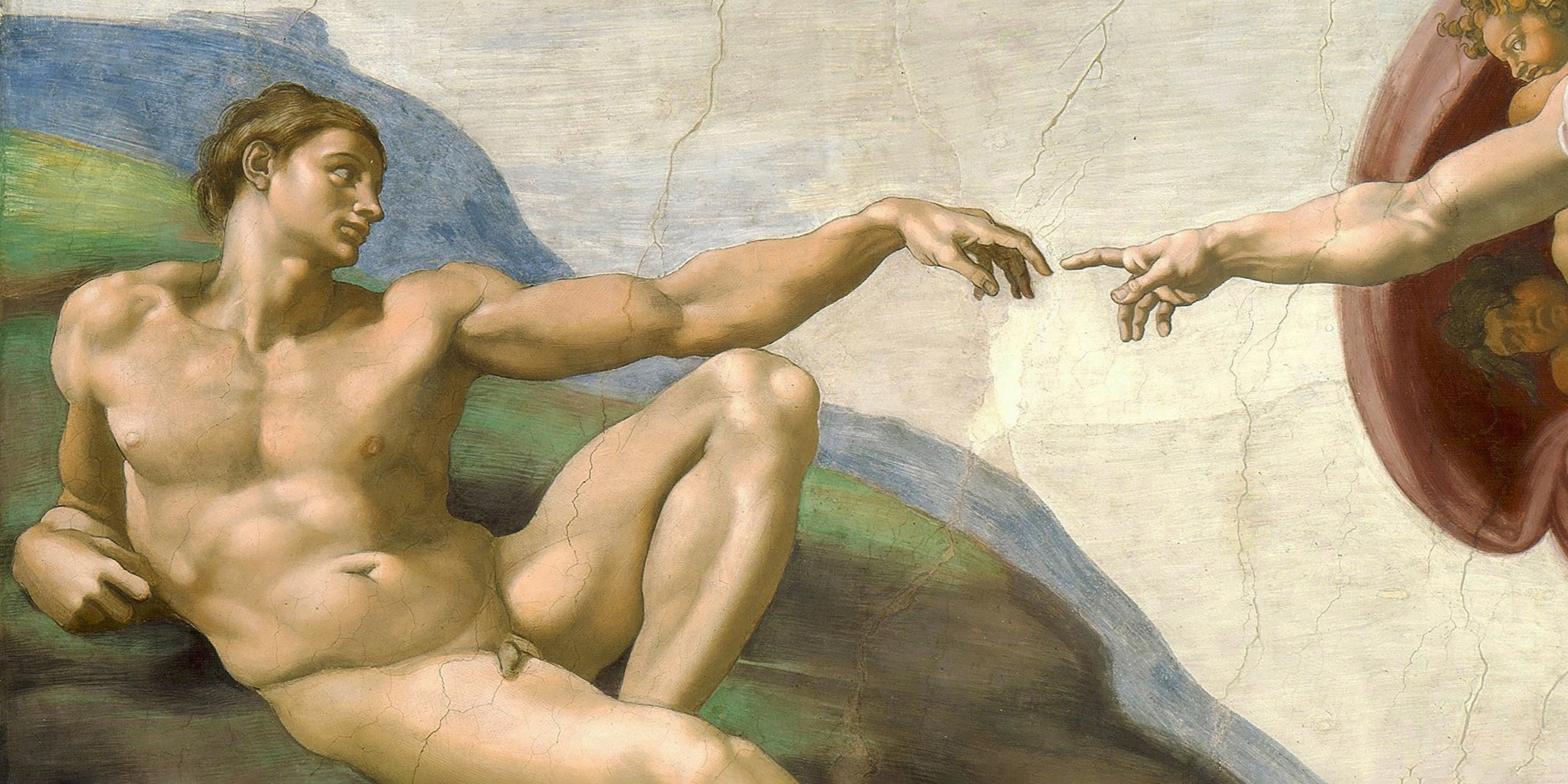

The COBE satellite observes the first moments of the Big Bang, the very flash of the Creation. The superconducting supercollider, if built, will allow us to experience conditions that existed in the earliest universe, as matter came into existence out of the primordial light.

Massively parallel-processing computers, with fractals and other kinds of computer-based mathematics, may (in my opinion) lead to the most sweeping transformation of science since the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century.

PCR provides a way to replicate tiny quantities of DNA millions of times over; it may turn out to be the most important invention of the 20th century. The Genome Project will provide a complete genetic blueprint for a human being — word by word, letter by letter.

The scanning tunneling microscope allows us to “see” individual atoms and move them about at will.

Fusion and superconductivity will transform the way civilization produces and uses energy.

SETI may answer the question: Are we the unrivaled lords of the cosmos, or merely commonplace?

This stuff is important, hugely important, and about it we know — as a people — almost nothing. Meanwhile, we wallow in the wildest forms of superstition and discredited myths. Why?

The high school students to whom I spoke had excellent answers. We can relate pseudoscience and superstition to our personal lives; science, on the other hand, is remote and forbidding. Pseudoscience and superstition are easy to understand; science is complex and inaccessible. The former are part of our history, literature, and culture; the latter are as new as yesterday. The popular media strongly reinforces the former; the latter are relegated to a corner of the curriculum and forgotten.

Thus, the schizophrenia of our age: We embrace science as the provider of our health, wealth, and technologies, yet we live our lives as if none of it were true. We pretend we still inhabit the Earth-centered universe of our ancestors, in which even the stars are attendant upon of human lives, although everything we have learned about the universe suggests otherwise. We wrap ourselves in easy truths, and take what we can get from science, no questions asked.

We want to have our cake and eat it too.

There’s nothing wrong with that, I suppose, nothing wrong with living with two contradictory kinds of truth. However, it seems to me that in doing so we denigrate that which is most wonderful about us — the capacity to know. To explore the vast cosmic reaches of space and time. To unravel astonishing mysteries of life and intelligence. To encompass within the human brain an image of a universe of almost unimaginable scope, complexity, and beauty.

The problem, of course, is that the scientific image of the universe is almost unimaginable. So we shall just have to become more imaginative, more daring, more willing to stretch. In that, we will be better served if scientific knowledge is wrested from scientists by poets, artists, historians, philosophers, and theologians, and transformed into a new vision of human worth, expressed in ordinary language.

It has happened before. It happened in the Enlightenment, when the science of Copernicus, Galileo, Descartes, and Newton was forged into new instruments of art, music, literature, religion, and political equality. It could happen again, this time as part of a global culture, incorporating the collective wisdom of the past into a new synthesis with science.

It better happen. Otherwise we will continue on our schizoid track, beholden to scientists, benumbed by technology, lapsed in superstition, frightened and ignorant of what is good and best within ourselves.