Originally published 25 November 2003

The Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, is one of New England’s hidden treasures. Next time you are driving Interstate 95 between Boston and New York, pop off at Exit 70 and treat yourself to an exhilarating look at early 20th-century American Impressionist art.

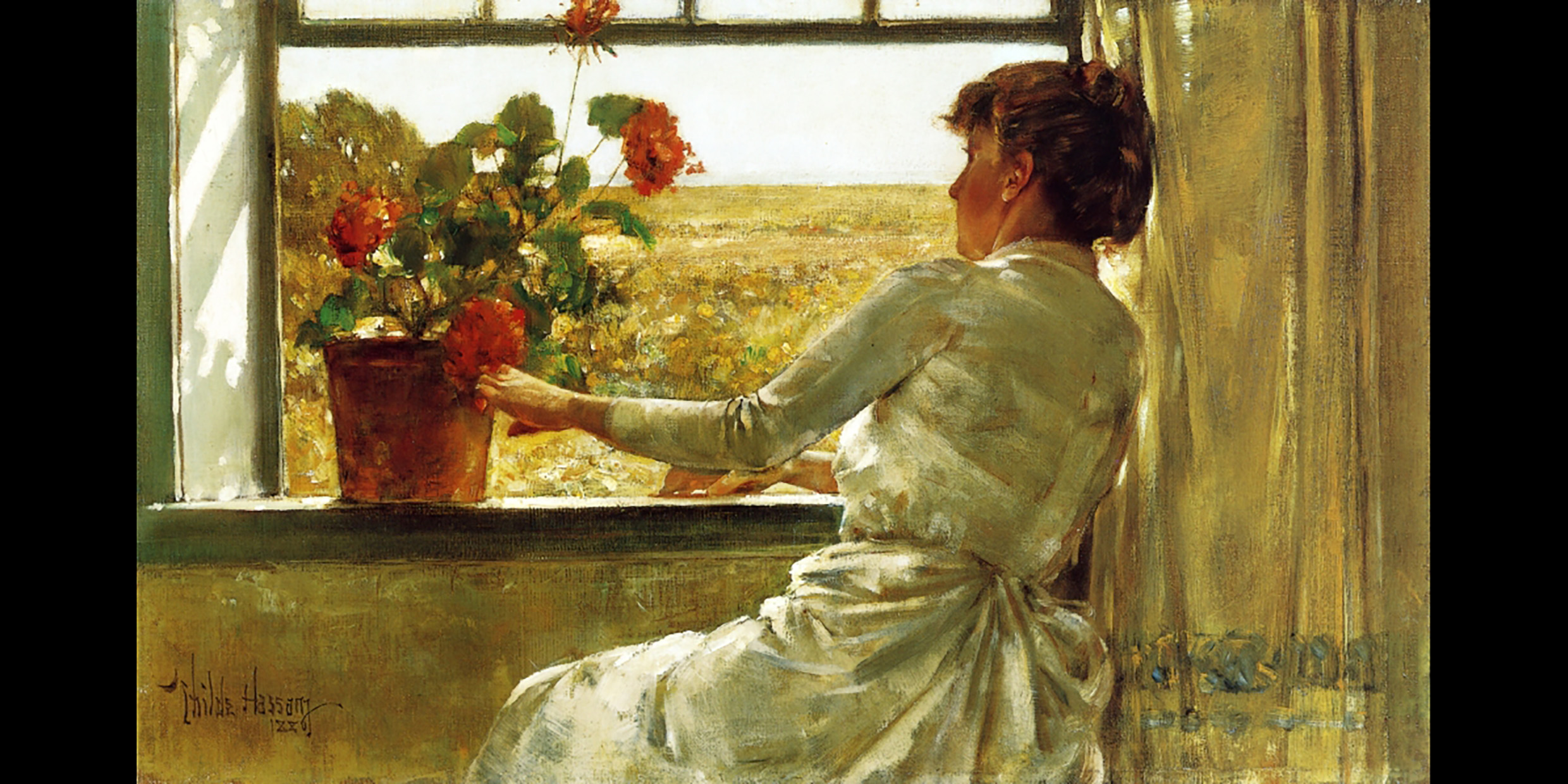

This is the place where American Impressionism was born, in 1903, when the landscape painter Childe Hassam took up residence in Miss Florence Griswold’s boarding house.

The house was originally the home of sea captain Robert Griswold. For much of the early 19th century it was the finest mansion in town, and Old Lyme was a thriving seaport. Then came steam-powered vessels, and the fortunes of the town and the Griswold family fell into decline. By the end of the century, Florence, one of four Griswold children, was taking in boarders to make ends meet.

When Hassam arrived, the Griswold house had already become a fledgling artist colony. Under Hassam’s influence, Old Lyme became a lively center of Impressionist painting, called the “American Giverny,” after Claude Monet’s home in France. “Miss Florence” was the colony’s guardian angel.

The Griswold mansion is now a showcase for paintings of the artists who lived and worked there. Nearby, a glistening new museum building exhibits a broader range of art — including contemporary art — in the context of American Impressionism.

As I admired the museum’s collection of stunning landscapes — rivers, marshes, meadows, craggy outcrops, rugged seacoast — painted in and around Old Lyme, I could not help but think of a recent report of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, describing how New England’s remaining unspoiled landscapes are being heedlessly destroyed. According to the report, every day 40 acres of Massachusetts forest, farmland, and open space are being developed, mostly to build homes. The homes are bigger than ever, and sit on larger lots, though families are shrinking in size.

“It’s the ‘mansionization’ of Massachusetts,” says Jack Clarke, director of advocacy for Mass Audubon.

Sensible planning, mandating smaller houses on smaller lots adjacent to already built-up areas, would help preserve New England’s natural beauty and wildlife habitats, with some part of development costs set aside for towns to buy up remaining green spaces. Instead, we have residential sprawl and strip-mall commercial development that reaches from town to town.

Landscapes that might have inspired Old Lyme artists a hundred years ago are lost.

Landscapes can inspire art. And art can inspire landscapes. The Old Lyme Impressionists were working at the same time that Charles Eliot and other disciples of the American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted were creating artful landscapes such as the Middlesex Fells and Blue Hills Reservations near Boston.

What Eliot said to the Boston Trustees of Reservations in 1891 might have been a preface to the Audubon report: “Here is a community, said to be the richest and most enlightened in America, which yet allows its finest scenes of natural beauty to be destroyed one by one, regardless of the fact that the great city of the future which is to fill this land would certainly prize every such scene exceedingly, and would gladly help to pay the cost of preserving them today.”

For many conservationists, “natural” means “non-human.” They urge us to leave wild places alone. It is too late for that. Human consciousness is as natural a product of evolution as bluebirds or great blue whales, and it trumps all other kinds of organic life. Like it or not, the entire surface of the planet Earth is going to be a human artifact.

But an artifact can be artful. We must work to achieve landscapes that honor the organic and respect other creatures, landscapes that provide relief from the “too insistently man-made surroundings of civilized life,” to quote Olmsted. Not wild nature, to be sure, but nature tamed by conscious intent.

The paintings of the early 20th-century American Impressionists show us how landscape can elevate the human spirit. Olmsted and his disciples taught us that art can elevate landscape. Our task is to see that the energy flows both ways, and that the surface of the planet becomes itself a work of sublime art.