Originally published 8 September 1997

Someday, maybe a century from now, tourists will drive down Martian Highway 27 between high-rimmed craters called Wahoo, Yuty, Shawnee, and Bled to a well-marked historical site at the mouth of the Ares Vallis where Mars Pathfinder touched down — or rather, bounced down — in the summer of 1997.

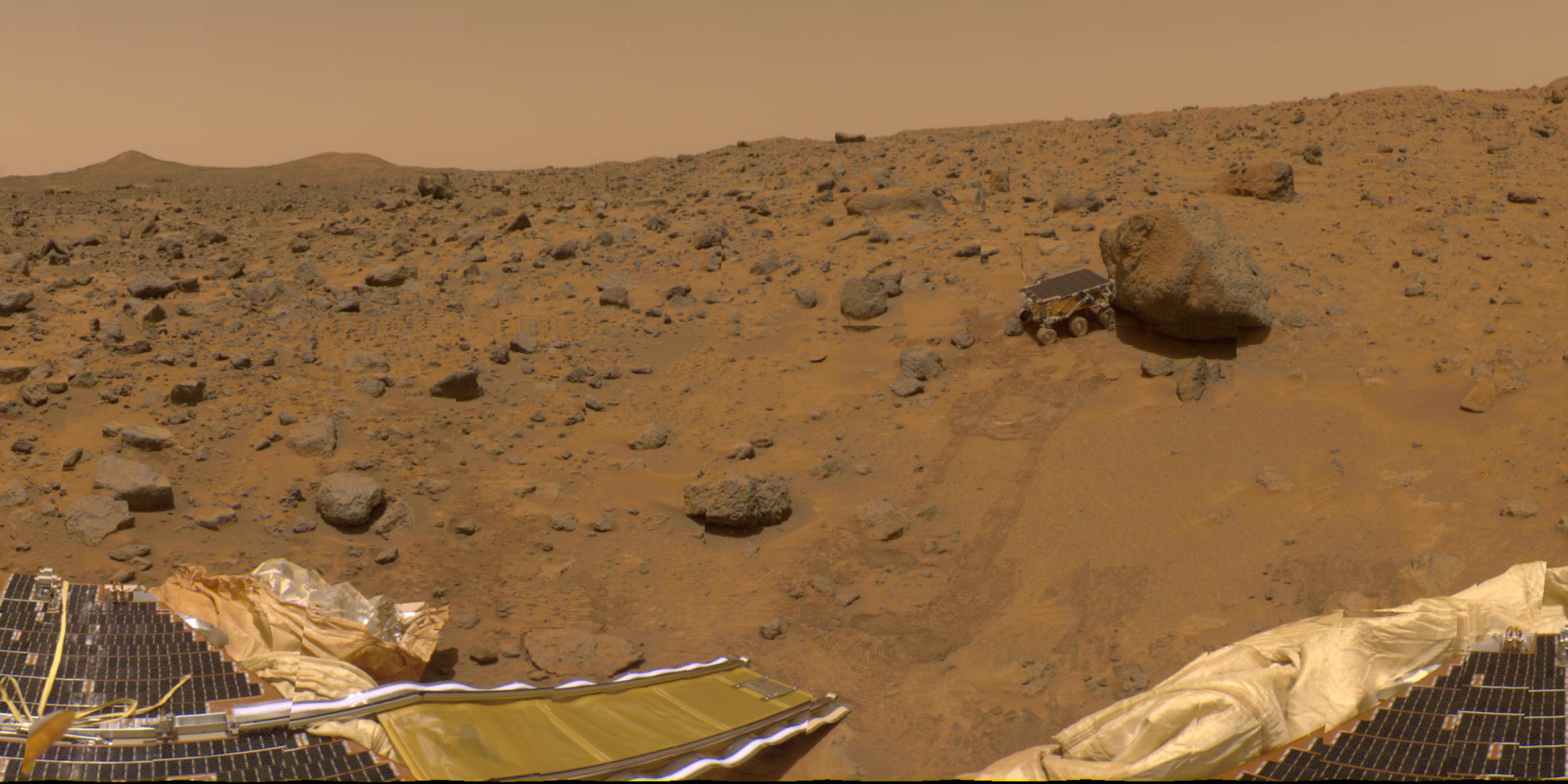

The weathered and sand-blasted craft may still be sitting in the red desert dust. Sojourner, the Martian rover, may also be on display. A tourist walking trail will pass by rocks known as Barnacle Bill, Yogi, and Mini-Matterhorn, along with Mermaid Dune, Roadrunner Flats, and Twin Peaks.

Those future tourists will recognize Pathfinder as an important step in the incremental accumulation of knowledge that made human colonization of Mars possible. But for us today, the information beamed back to Earth from Pathfinder seems remarkably prosaic.

The surface of Mars appears very like the surface of Earth. It has dust and pebbles and boulders. Hills and valleys. Winds and weather. Day and night. Seasons. Photographs of the Pathfinder landing site are indistinguishable (to the inexpert eye) from photographs of, say, certain parts of Nevada.

The big discovery of the summer of ’97 is that there is no discovery.

Pathfinder’s message from Mars is this: Our place in the universe is unexceptional.

We have yet to come to terms with this message. Many more missions to many more places, perhaps even to the planets of other stars, will be necessary before we at last surrender our ancient claim to uniqueness and centrality.

Anthropologists tell us that many tribal peoples designated a central place in the village as the center of the cosmos; then, as their horizons widened, those peoples discovered a village next door with another center. Medieval European maps showed a central Europe rimmed with wildness and barbarism; when Europeans reached the Americas in the late 15th century, they found folks just like themselves, living in cities, raising domesticated plants and animals, worshiping gods with human faces.

Copernicus displaced the Earth from its central location in the cosmos. Twentieth-century astronomers bumped the sun into an ordinary suburb of the Milky Way Galaxy. The Galaxy itself appears typical.

Every time we thought ourselves special, central, or unique, we have been chastened by experience. Some scientists and philosophers have raised this recurring disappointment to the level of a principle — the so-called Mediocrity Principle: All things considered, the universe probably looks much the same from here as from anywhere else. We are cosmically mediocre.

The word “mediocre,” although accurate in its original meaning (“of middling degree”), has a pejorative connotation. “Fairly bad,” says the dictionary. The Commonplace Principle might be a better way to put it: Our place in the universe is commonplace.

But again, “common” bears a negative connotation. “Of inferior quality, low-class, vulgar,” says the dictionary in one of its several meanings.

In fact, our language of middling degree is loaded with value. “Mediocre,” “common,” “average,” “ordinary”: All of these words carry a hint of inferiority. Throughout human history, we have been in thrall to a hierarchical view of the universe, a “Great Chain of Being” that descends from the throne of God through choirs of angels, popes, kings, nobility, serfs, slaves, ranked orders of animals and plants, to the baleful, inanimate dregs of creation at the center of the Earth. To be average in such a universe is to be less than best.

We resist the Mediocrity Principle because we are conditioned by our history to think of “upper classes,” “the divine rights of kings,” “superior races,” “the king of the beasts.” We tenaciously reject the fundamental tenet of cosmic democracy — that the Earth is average — and assert instead the primacy of our place in creation. We are unique, central, special, the apple of the Creator’s eye. The stars and planets attend to our human whims. The galaxies are decorations for the human night.

But everything we have learned in science for thousands of years suggests that the Great Chain of Being is a fraud; indeed, often a pernicious fraud. There is no biological basis for racism, no “divine rights” in our DNA, no “ascent of man” in evolution. Differences of physics, chemistry, and biology are matters of degree, not quality.

To be ordinary, to be average, to be commonplace, is to be at the center of a bell-curve of diversity, neither good nor bad.

We need to wrest language from its hierarchical history. We need a fanfare for the common man, the common species, the common planet, the common star. We need to look anew at our place in the creation — a place that appears to be utterly commonplace — and rethink what it means to call ourselves good. Not good because we are at the top of the heap, but because the whole heap is good.

The amount of silicon dioxide (quartz) in the Earth’s crust is between 50 and 60 percent. When the Martian rover snuggled up to a Martian rock called Barnacle Bill, it measured 55 percent silicon dioxide. Earth’s crust is about 45 percent oxygen, 25 percent silicon, 6 percent aluminum; ditto for Mars, according to the rover. What’s up there are not crystalline spheres pushed by angels whose hems we touch from the top of the terrestrial ladder. What’s up there are rocks — average, mediocre, ordinary, commonplace rocks.

Little Sojourner, tootling around on the surface of Mars, rebukes our conceit.