Originally published 2 September 1991

Ventry, Ireland — It was the summer of the jellyfish. On almost every retreating tide the beach was jam-packed with jellies. A walk at water’s edge required constant attention to what was underfoot; few experiences are more unpleasant than stepping barefoot into a quivering cushion of jellyfish jelly.

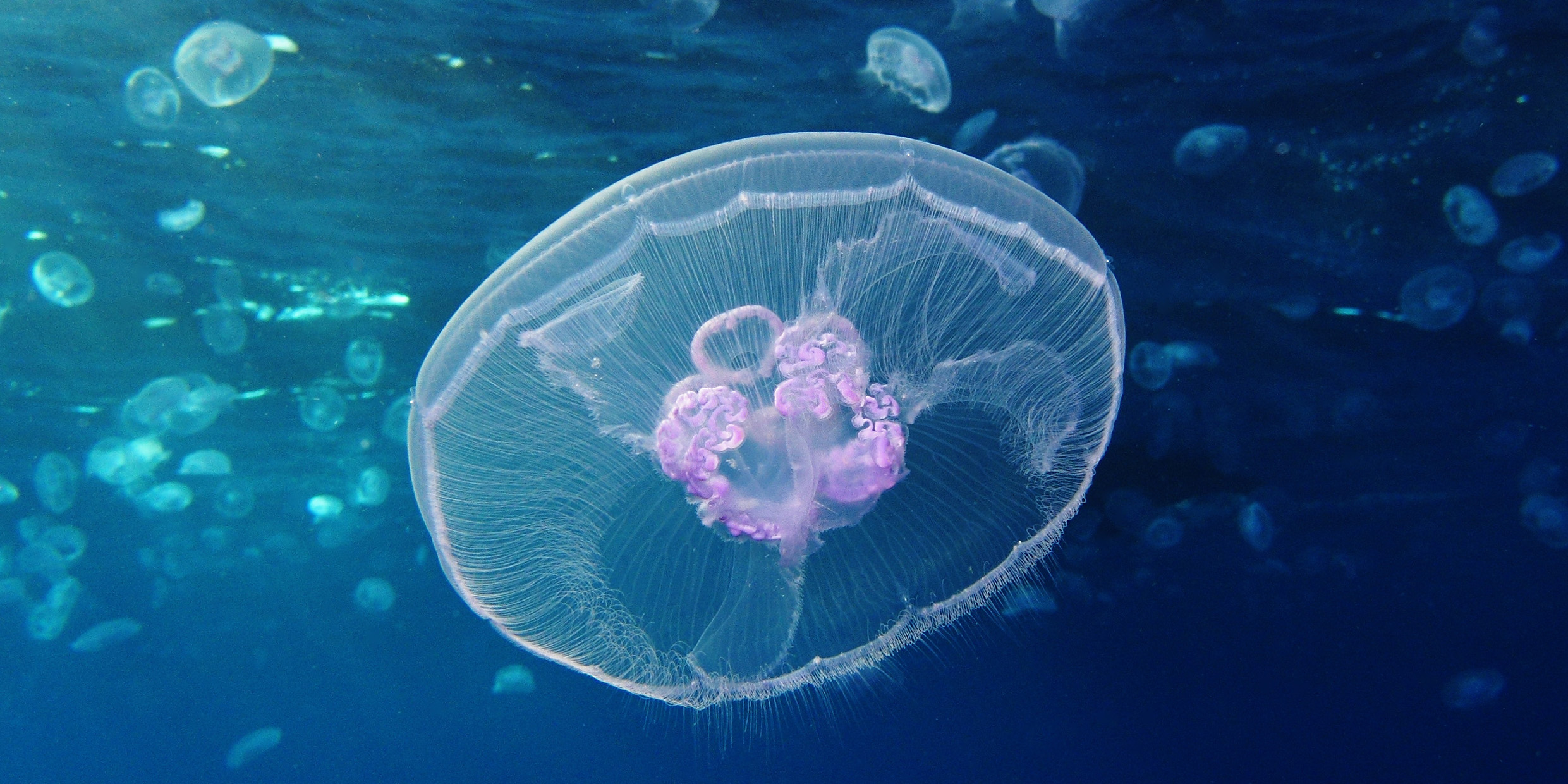

These blobs of tentacled goo have been especially abundant on Irish coasts all summer long. On our beach they are mostly Aurelia, the common moon-jelly, with four elegant purple rings near the top of its transparent bell. The rings are the animal’s sex organs. There’s not much else to see. The fringe of stinging tentacles (not dangerous in Aurelia) and the dangling mouth-arms under the bell are mostly invisible once the jellyfish is stranded on the sand.

From the kids at the water’s edge comes a constant litany of “Yuck!” “Gross!” “Disgusting!”

Poor kids. Poor jellyfish.

Lemmings, they say, throw themselves of their own volition into the sea, and sometimes pods of whales beach themselves en masse for reasons known only to the whales. But jellyfish don’t choose to inflict themselves on summer bathers. They travel at the whim of sea and weather, drifting where the currents take them, and if some combination of gyres and breezes dumps a thousand of them onto the sand where we want to swim, well, that’s hardly the fault of the jellyfish.

Aurelia’s lifestyle is altogether curious. Sometime in late summer the adult jellyfish release eggs and sperm into the water. Free-swimming larva resulting from fertilization attach themselves to rocks or seaweed on the sea floor and transform themselves into tiny plant-like polyps, each polyp shaped like a stack of inverted saucers. Thus anchored and secure, they pass the winter. In spring the saucers bud off tiny jellyfish, which grow to become big jellyfish, which — if winds and tides are perverse to jellyfish and humans — find themselves high and dry and squashed.

Ideal mix for survival

Jellyfish stranded on the sand don’t have much of a future in any case. They quickly die and evaporate. Their bodies are 99 percent water; they have fewer non-aqueous ingredients than weak lemonade. A mousse or a meringue is a Rock of Gibraltar compared to a jellyfish.

But mousses and meringues are not alive, and life is what it’s all about. For all of their simplicity, jellyfish are amazingly efficient machines for making other jellyfish. Their mix of water and Jello may be 99-to‑1 but that appears to be an ideal recipe for survival.

Back in the 1950s, geologist Martin Glaessner discovered rocks in the Ediacara Hills of southern Australia that contain fossils of the first multicelled organisms to flourish on this planet, a diverse community of soft-bodied organisms that was somehow buried in fine sand and preserved as delicate impressions in sandstone. The rocks are nearly 700 million years old. And who was there at the very beginning of multicelled life? You guessed it — jellyfish.

Armored trilobites, thunder-footed dinosaurs, and saber-toothed tigers have come and gone; the watery jellyfish have endured. They have outlasted animals with bulk and brains. Their strategy for survival has been spectacularly successful: Keep it simple, go with the flow.

In jellyfish we see life reduced to its essentials. Under those pretty purple reproductive rings are a mouth and four dangling arms with nothing to do except stuff the mouth. Eat and drift, drift and eat: it’s the original hobo existence. And, if you live in the sea, transparency is more or less equivalent to invisibility — another survival secret of the hobo.

Muscle movement

Jellyfish are not entirely without self-propulsion. In quiet tide pools they manage to push themselves this way and that by rhythmically contracting muscles (such as they are) on the lower rim of the bell, but how they decide where they are going is a mystery. They have eyes of a sort at the base of their tentacles, and other rudimentary sensory organs, but its hard to imagine that these inverted bowls of transparent slime can have much of an IQ. When great numbers of them wash up on the beach it is not intellect or will that put them there, but quirks of circulation in the great global engine of sea and air.

Where did our hordes of Aurelia come from? Probably rounded up cowboy-style by circulating currents in coastal waters and flung onto our shore by a southwest wind. The fluke of their appearance in such multitudes is part of that vast system of flukes we call the weather. If meteorologists can’t reliably predict what the weather will be two days from now (and around here they can’t), its because the agitations of water and wind are so damnably complicated.

The agitations don’t agitate the jellyfish. They go where the currents and tempests take them. Theirs may not be the most independent sort of existence (and for the kids on the beach it can be positively yucky), but it has served jellyfish well for 700 million years. In the great Darwinian struggle to survive, going with the flow has much to recommend it.