Originally published 24 January 1994

“I believe that for his escape he took advantage of the migration

of a flock of wild birds.”

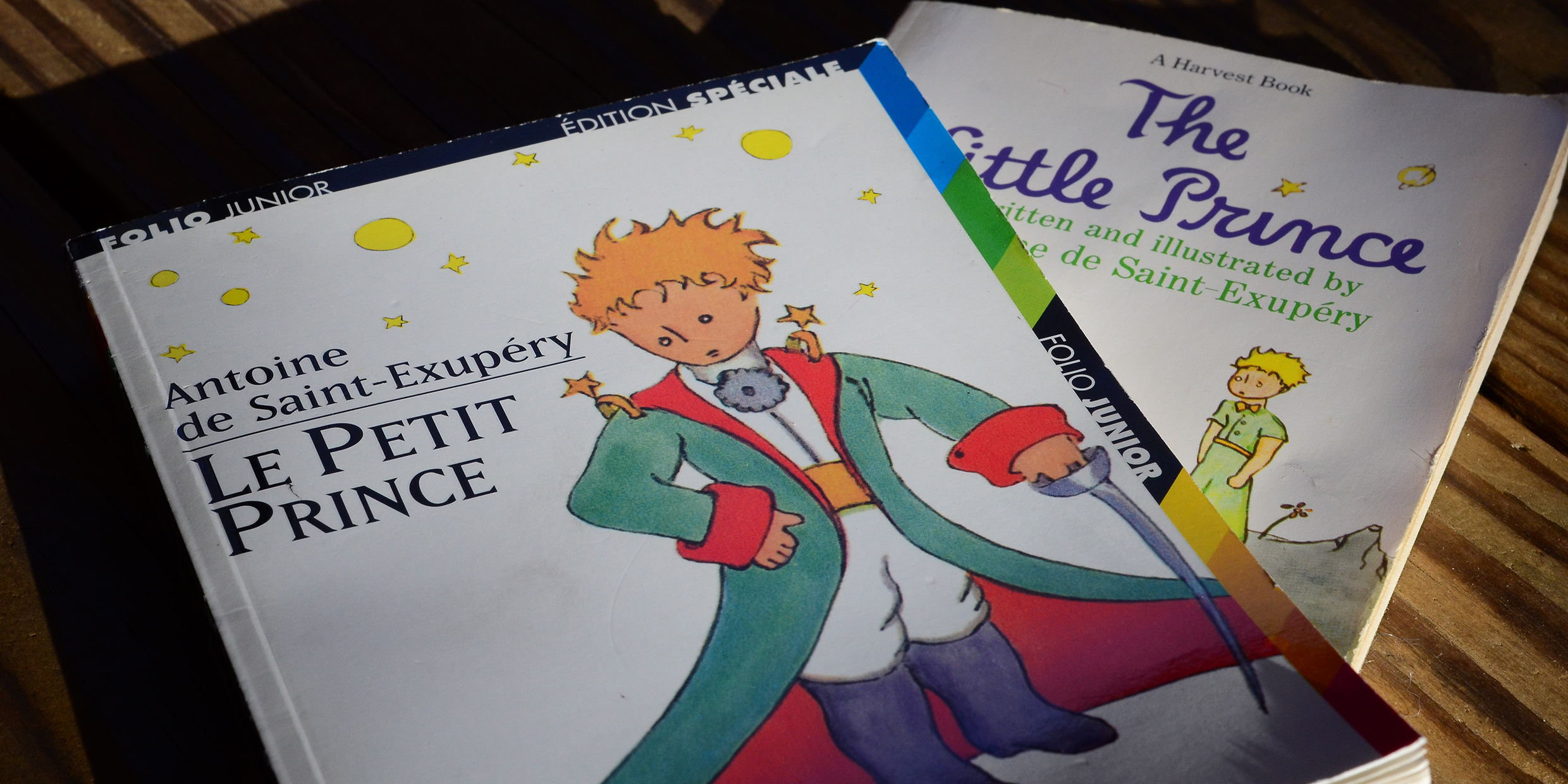

Many people will recognize this caption from the frontispiece drawing of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. The drawing shows the little prince being lifted from his planet — an asteroid, actually — by a harness attached to 11 birds of indeterminate species.

“Eleven birds.” “Indeterminate species.” Oh dear, I am falling into the trap that Saint-Exupéry’s book is a caution against. I am counting and categorizing when what is called for is childlike acceptance and

wonder.

I am being a grown-up.

“Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is tiresome for children to be always and forever explaining things to them,” wrote Saint-Exupéry. In the context, it is not difficult to understand his sentiment. As he wrote and drew his book at a rented house on Long Island, N.Y., through the summer and autumn of 1942, grown-ups were slaughtering one another with a terrible ferocity in his native France, and around the world.

Saint-Exupéry was a pilot and a writer. He flew often over North Africa at a time when solo flight involved great risks. The Little Prince tells of a pilot who has crashed in the Sahara Desert who meets a mysterious boy from another place. The book has nothing good to say about scientists, lumping them in with kings, businessmen, and other grown-ups who have little sense of what is truly important.

Almost immediately the book became a classic, and has remained popular with children and grown-ups. To celebrate the half-century that has passed since its publication in 1943, Harcourt Brace and Company has issued a handsome boxed edition containing many of Saint-Exupéry’s unpublished preliminary sketches.

The golden-haired little prince lives on a tiny planet, scarcely larger than himself, which scientists — as scientists are wont to do — have designated Asteroid B‑612, To the little prince, it is simply “my star,” and he lives there with a haughty but much loved rose. The most charming drawings in the book are those of the little prince on his minuscule planet, digging out the sprouts of troublesome plants, cleaning his three volcanoes (two active, one extinct), and caring for his rose.

And, of course, I cannot resist being a grown-up. After all, I was trained as a scientist. It is my business to make calculations, to weigh, measure and evaluate.

For example, a bit of basic physics shows that the little prince’s planet is totally unfeasible as a habitat.

Asteroid B‑612 appears to be about 10 feet in diameter. If we assume an average density about the same as that of Earth — 5.5 grams per cubic centimeter — then the little prince would weigh less than a thousandth of an ounce.

He would float in the breezes like a thistle seed.

Except there wouldn’t be any breezes. The little prince’s planet would not have enough gravity to hold an atmosphere. Any molecules of gas that emerged from his two active volcanoes would drift off into space.

But his planet could not be volcanically active. The volume of a sphere is proportional to the cube of the radius, while the surface area depends on the square of the radius. As a sphere gets larger, its volume increases faster than its area, and therefore a larger planet will have more internal heat and less surface area, relatively speaking, for the heat to escape. Four billion years after the formation of the solar system, the Earth still sputters with volcanoes. But the little prince’s asteroid is a million times smaller than Earth, and would have long since cooled to cold rigidity even if it were molten at its beginning.

Which it would not have been. The solar system formed when gravity pulled together gas and dust from a vast nebula, This clumping process generates heat. But the little prince’s planet contains so little material that the amount of heat would have been insignificant. Not nearly enough to melt anything.

Nor would his planet have been spherical, unless it melted, which it didn’t.

In short, this whole business of Asteroid B‑612 is a sham. Physically and astronomically impossible.

Consider that flight of birds that the little prince uses for his escape: Completely unnecessary. The upward speed that an object must have to overcome the gravitational pull of a planet is called the escape velocity. The escape velocity of Earth is 22,000 miles per hour, which is the speed a rocket must acquire to leave the Earth. The escape velocity for Asteroid B‑612 is about five-thousandths of a mile per hour. The little prince could leave his planet by making a little jump.

In fact, if he had any spring to his step at all he would have a hard time staying home. He would need to tether himself to his planet the way an astronaut is tethered to a space ship.

And what about the rose? It needs air, water, soil. There can be no…

Whoa! I’m taking this grown-up business too far. I should stop my calculations and listen to Saint-Exupéry: The proof that the little prince existed on a planet scarcely larger than himself is that he was charming, that he laughed and that he had a rose.

If anyone has a rose, implies Saint-Exupéry, that is proof enough that he exists.