Originally published 8 September 1986

Was Columbus was the first European to set foot on American soil, in 1492? You may agree if you are an American of Italian descent. But if you are Norwegian, or Portuguese, or Irish, or almost any other nationality, you will probably have your own candidate for the first European to reach these shores. There is no dearth of entries in the “Discover America” sweepstakes.

The strongest claim to an early European presence in America surely goes to the Scandinavians.

It has long been held that Vikings under the leadership of Leif Erikson sailed successfully to North America via the Viking colonies in Iceland and Greenland as early as the 10th century. The claim is based on references to a “Vinland” west of Greenland in the Norse sagas. Countless physical evidences of a Viking presence in North America have been adduced, but most have failed to impress the scientific community.

However, archeologists working at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland have discovered what are presumed to be the remains of a Viking settlement. The evidence is impressive, even to a skeptic. The Scandinavians have moved decisively ahead in the sweepstakes.

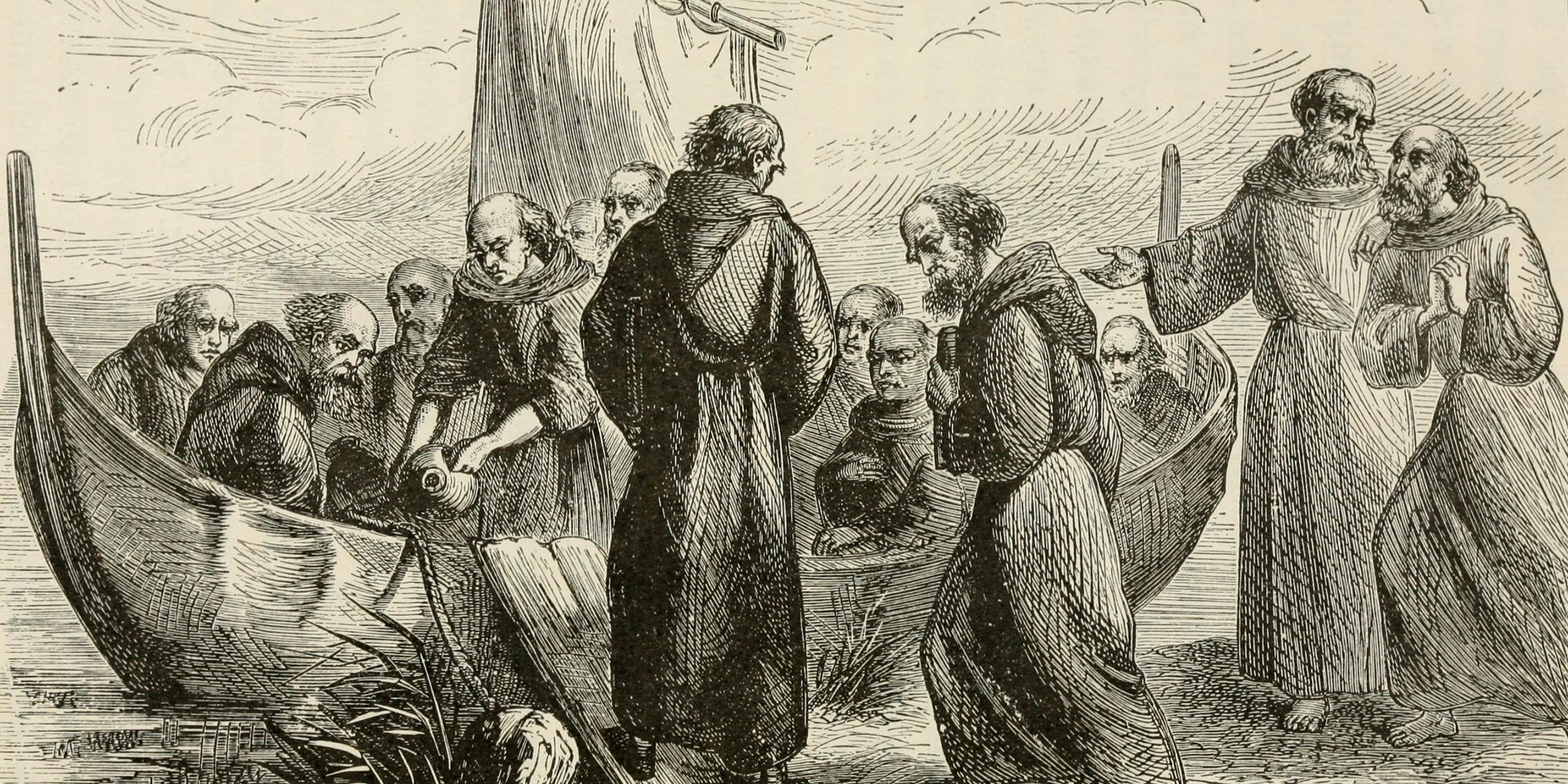

But any American who was educated in parochial schools by Irish nuns knows that Leif Erikson and his crowd were latecomers. Five hundred years before the Vikings and a thousand years before Columbus, Saint Brendan the Navigator sailed in a boat of wood lath and leather from the Dingle Peninsula in Ireland and after a voyage of many months reached America. There is no doubt in Irish minds that their man should take the prize.

The Irish claim is based upon a remarkable book, the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis, known more simply as the Navigatio or Voyage of Brendan. The story is of undoubted antiquity. There are more than a hundred extant medieval versions of the manuscript, several of which appear to date from as early as the 10th century. Some believe that the Navigatio was first produced in Latin around AD 800, and that the story itself has its origins in the 6th century.

Journey of Saint Brendan

The story tells of the journey of Saint Brendan and 17 companions to a large and fertile land across the Western Sea. It is a fabulous tale, full of miracles and strange events. But no Irishman doubts that the Promised Land of the Saints, as recorded in the Navigatio, bears a striking resemblance to North America.

In 1976, the adventurer Tim Severin, sailed in a boat of lath and leather from Brandon Creek at the foot of Brandon Mountain in the Dingle Peninsula (the traditional setting-off point of the saint) to recreate the reputed voyage. He took care to construct his boat in the medieval way and with medieval materials (similar craft, called currachs, are still built and raced in the Dingle Peninsula). In two summers’ sailing, he reached Newfoundland, proving to his own satisfaction that the voyage described in the Navigatio was possible.

Severin found many points of correspondence between places and events described in the medieval manuscript and those he encountered on his own voyage. For example, Severin saw icebergs that resembled the “floating pillar of crystal” reported in the Navigatio. And the “hot rocks” that pelted Brendan and his companions at one island stop could refer to ejections from an Icelandic volcano.

Is the tale that unfolds in the Navigatio more than a wild farrago of seafaring yarns? Can the Promised Land of the Saints, like Vinland before it, be linked to America with something resembling scientific certainty?

No one doubts the real existence of Brendan himself. He lived in the west of Ireland in the 6th century and traveled widely. But his discovery of America must be considered pure conjecture. Although many North American artifacts have been ascribed to an early Irish presence on these shores, not a single archeological discovery qualifies as suitably scientific evidence for the truth of the Brendan voyage.

A few weeks ago, Irish archeologists completed a survey of the ancient artifacts and monuments of the Dingle Peninsula. It was the most detailed archeological survey ever undertaken in Ireland. The 460-page report of the survey describes over 1,700 sites, ranging from Neolithic settlements to 18th century castles.

Legacy of the saint

Sites that have a folk connection with Saint Brendan figure prominently in the survey. It seems that almost every townland has a “Saint Brendan’s Well.” There are dozens of primitive stone “houses” and “oratories” that were supposedly used by the saint. One flat stone with cup-like depressions is known locally as “Brendan’s kneeler.”

On the top of Brandon Mountain (probably named for the saint) the archeologists recorded an impressive array of artifacts that are associated with the saint. According to tradition, this is where Brendan made his decision to go west. On a remote sea cliff near the base of the mountain the surveyors mapped the reputed hermitage where Brendan retired to prepare for his voyage. And if only in name, the saint’s presence is attached to the nearby creek where he supposedly set sail.

The new archeological survey found nothing that would reinforce the Irish claim to have discovered America, but it did confirm that the folk memory of the presumed discover is still very much alive.