Originally published 26 February 2002

It was inevitable that sooner or later we would ask bacteria to make electricity.

I mean, what else do they do but hang around in staggering, colossal numbers, doing pretty much nothing but eating, wiggling, and reproducing. Why not ask them to put their talents to practical use, as in a battery, for example?

That’s just what a team of scientists have done, led by Derek Lovley and Daniel Bond of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. They have found a species of bacteria that can make electricity from sea-floor sediments, by generating excess electrons that collect on electrodes stuck in the mud. So far, the microbes have made only enough current to power a pocket calculator, but you can be sure their efficiency will be improved.

It’s no great stretch to imagine a domestic septic tank that is also a big bacteria-powered battery supplying your house with electricity. Recharge your battery by flushing the toilet.

OK, I’m fantasizing, but not wildly so. In fact, I would go so far as to say that, by the end of the century, natural or genetically modified bacteria will be generating megawatts of electricity, making the most of our liquid and gaseous fuels, cleaning up waste, refining minerals, producing food, fertilizers, pesticides and medicines, maybe even computing.

And, of course, microbes will be the weapon of choice in warfare, too, assuming we still have a hankering to kill each other.

Many of these things already have been achieved. For example, genetically modified bacteria turn organic waste into ethanol automobile fuel, make insulin, and perform dozens of other useful functions. The researchers who first isolated the human brain hormone, somatostatin, needed a half-million sheep brains to collect a pinch of the hormone; a bucket of bacteria can quickly produce the same amount.

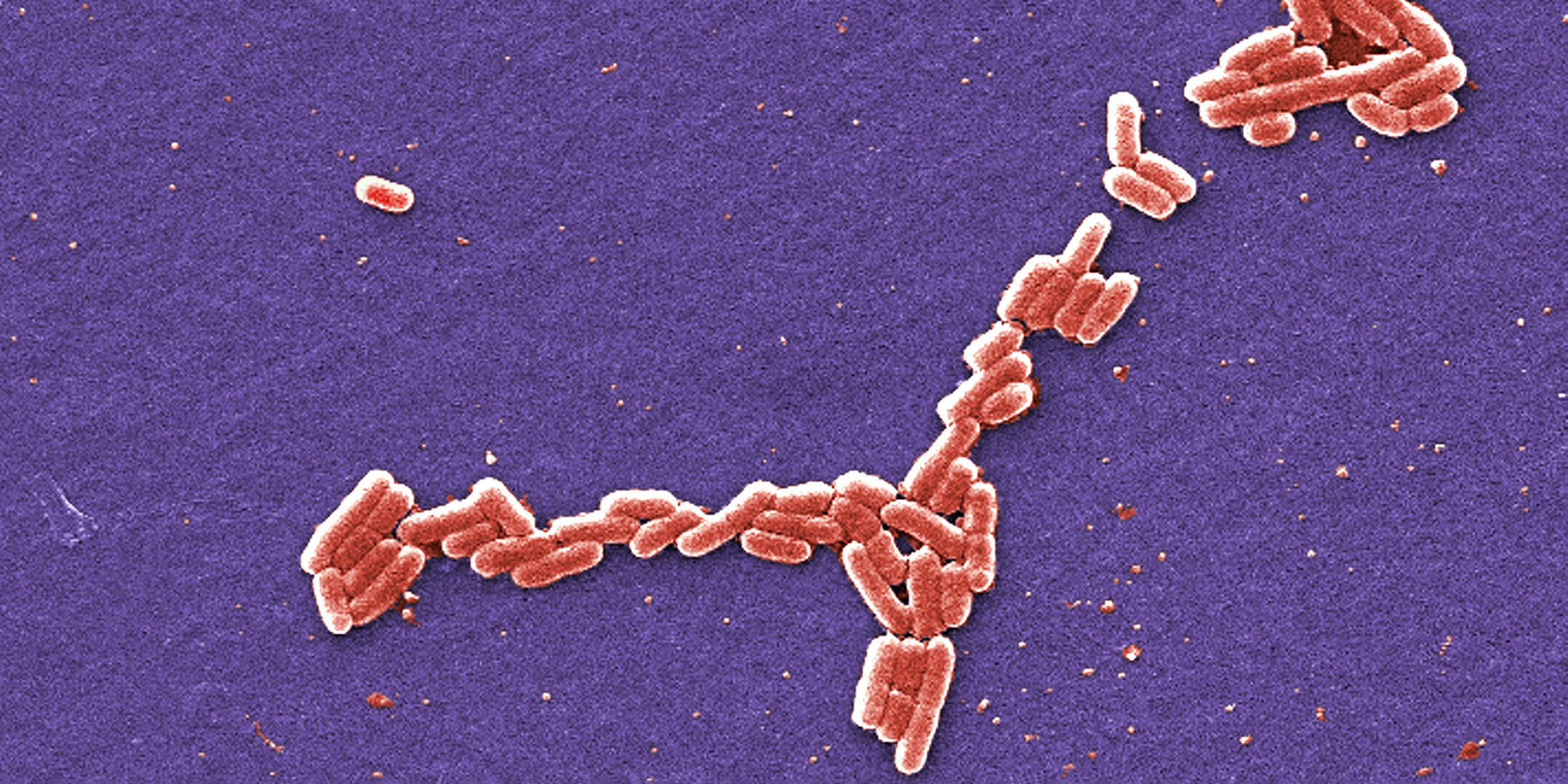

And getting bucketsful of bacteria is no problem. You can’t see them, but they are everywhere. There are a million bacteria on each square inch of your dry skin; in damp places, your mouth, for example, a thousand times more. The E. coli bacteria in your intestinal tract, lined up end to end, would reach from Boston to San Francisco. A substantial fraction of your body weight is not you at all; it is the microbes that use your body as a small planet.

The vast majority of creatures that live in the oceans are a hundred times smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. Pound for pound, there may be more bacteria living in the rocks under your feet, down to a depth of a mile or more, than all life on the surface of the Earth, elephants and great blue whales included.

And, of course, all these bacteria are not just sitting around doing nothing, as I disrespectfully suggested. We depend upon them in myriad ways, many of which we may not yet even understand.

Photosynthesizing bacteria in the oceans are the base of the aquatic food chain. They also help maintain the composition of the atmosphere, and regulate the climate. Bacteria that live on the roots of certain plants take nitrogen from the atmosphere and render it in a form useful for plants and animals. Still other microbes decompose organic debris and so help recycle nutrients that sustain entire ecosystems. Your compost heap and septic tank are productive bacterial communities.

Bacteria make yogurt and sauerkraut. Yeasts, single-celled fungi, make bread and wine. And those zillions of E. coli in your intestinal tract? They earn their keep by making vitamins and other useful chemicals, and by competing with invading bacteria that might cause sickness or infections.

So, it’s not fair to accuse bacteria of indolence. But it’s also true that microbes ain’t seen nothing yet compared to what we will soon ask them to do directly for human benefit.

Bacteria-powered batteries are just the tip of the bug-tech iceberg.

A century from now the planet will belong to two creatures — humans (the brains), and bacteria (the brawn). All other creatures — elephants and great blue whales, bluebirds, and mosquitoes — will exist at our indulgence.

There are those who would say that even human intelligence represents the ultimate triumph of bacteria. Multicelled creatures probably got their start as alliances of one-celled organisms that previously lived on their own. Biologist Lynn Margulis, a champion of bacteria if ever there was one, has written: “It is not preposterous to postulate that the very consciousness that enables us to probe the workings of our cells may have been born of the concerted capacities of million of microbes that evolved symbiotically to become the human brain.”

Which raises the interesting question: Are we using the bacteria, or are they using us?