Originally published 14 May 2002

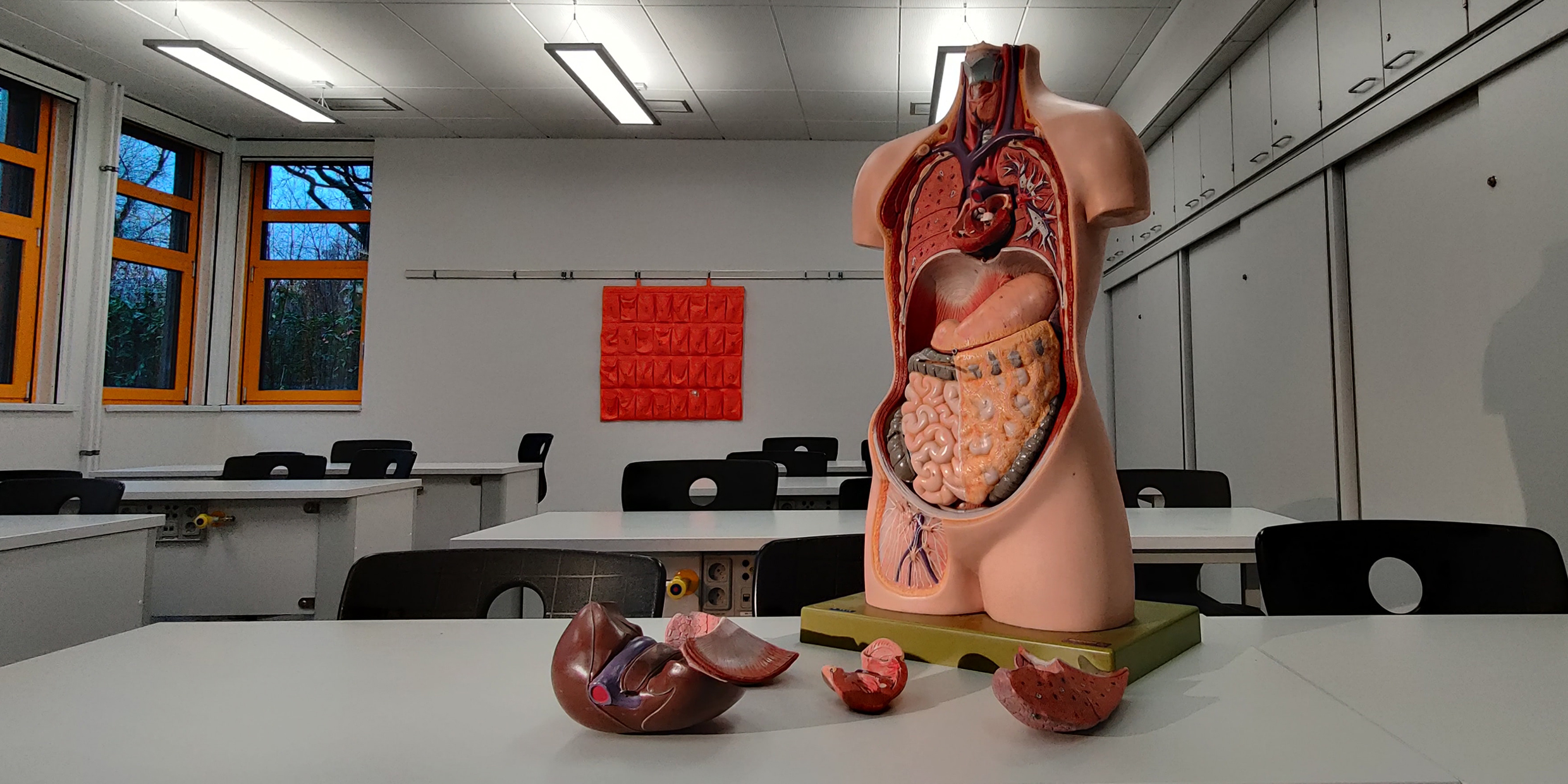

What a jumble! I’m sitting in a doctor’s examining room waiting for a checkup. On the wall is a poster chart of the human digestive system. The first thing I’m reminded of is my sock and underwear drawer. Everything thrown in a heap, all twisty and turny. No two socks that match. A long sock balled up with a short one and a pair of skivvies.

The drawer of a slob who can’t be bothered.

When you think about it, it’s a wonder how anything makes it from one end of the digestive tract to the other. An engineer might sort it out. Roll that small intestine up into a nice neat coil. Straighten out those kinks in the large intestine. Can you imagine the exhaust system of your car in such a tangle?

The human ear is another body part that could use the attentions of a good engineer. It seems astonishingly complex compared to a the tiny little microphone that lets my laptop computer respond to sound. Hammer, anvil, and stirrup: Where did those crazy little mechanisms come from? Five separate membranes. And three fleshy loops that seem, on the face of it, superfluous.

OK, admittedly the ear has a goofy Rube Goldberg ingenuity about it, but does it really need to be so complicated? It’s no surprise that my doctor doesn’t have a clue why I have ringing in my ear, or how to fix it.

And while we are at it, what about the human male’s use of the same penile passage for both reproduction and excretion. In primitive animals the use of one duct for both functions can be explained as a matter of efficiency, but in the higher animals the association of the two systems can lead to problems. An enlarged prostate, for example, presses against the bladder, causing urinary problems as well as reproductive malfunction.

In the course of evolution, this dual use of a single duct has been modified in females, with the shared passage being gradually shortened. In most female mammals, urine from the urethra passes only through the final part of the vagina. In human females and their closest relatives among the apes, the urinary orifice has moved completely outside the vagina.

In his book, The Pony Fish’s Glow, evolutionist George Williams draws attention to another wacky feature of the male reproductive-excretory system — the absurdly long tubes that carry semen from the testes to the adjacent penis, which make an unnecessary round trip up into the body, then back down again.

According to Williams, in the course of animal evolution, the testicles descended from deep inside the body to the scrotal sac behind the penis, presumably to provide cooling for the sperm. As the testicles moved toward the groin, the tubes connecting them to the penis should have logically shortened. But the piping got hung up around the ureters connecting the kidneys to the bladder, like a gardener’s hose that gets caught around a tree.

The testes-penis connection makes no sense at all from a design point of view, but it is readily explained by evolutionary biology.

I guess the point I’m trying to make is that much of the human body is an engineer’s nightmare, showing little in the way of intelligent design: which is just what you’d expect if our bodies evolved by a process of incremental changes acted upon by natural selection. The thing about evolution is this: Inevitably it moves toward evermore finely adapted organisms, but the end is not foreordained and the journey is something of a drunken stagger.

Now, before you accuse me of tossing an Intelligent Designer out of the picture, consider this: For all of the improvements an engineer might suggest for the human body, the body is still a thing that no engineer could hope to equal. Fabulously resilient. Capable of stunning feats of endurance. Exquisitely attuned to the environment. Agile, disease-repelling, self-repairing, purposeful, cunning.

Evolution by natural selection, for all of its jerry-rigged solutions, for all its failed experiments and blind alleys, is a wonderfully efficient way to populate a universe with diverse and interesting creatures. If I were an Intelligent Designer, and I had a hundred billion galaxies (at least) to fill with wonders, I can think of no way more efficient to do it than by genetic variations and natural selection of self-reproducing organisms.

In fact, engineers are increasingly using exactly this strategy to solve complex problems of design. Start with a prototype and a functional environment, make random changes, reinforce the ones that work, eliminate the ones that fail. Do all of this in multiple generations on a high-speed computer. Let the computer find the best adapted design. What you end up with may not be what you would have designed in the traditional way, but it’s usually better.

You want intelligent design? Try evolution.