Originally published 13 January 1992

The sky is full of tricks of light. Daytime radiances include rainbows, sun dogs, coronas, and glories. Recently, from the coast of Alaska, I saw a circumzenithal arc, the rare and famous “backwards rainbow” that appears high overhead. At nighttime add moon bows, noctilucent clouds, the gegenschein, and zodiacal light.

No trick of light is more elusive than the green flash. For 25 years I have sought it unsuccessfully. I’m still looking.

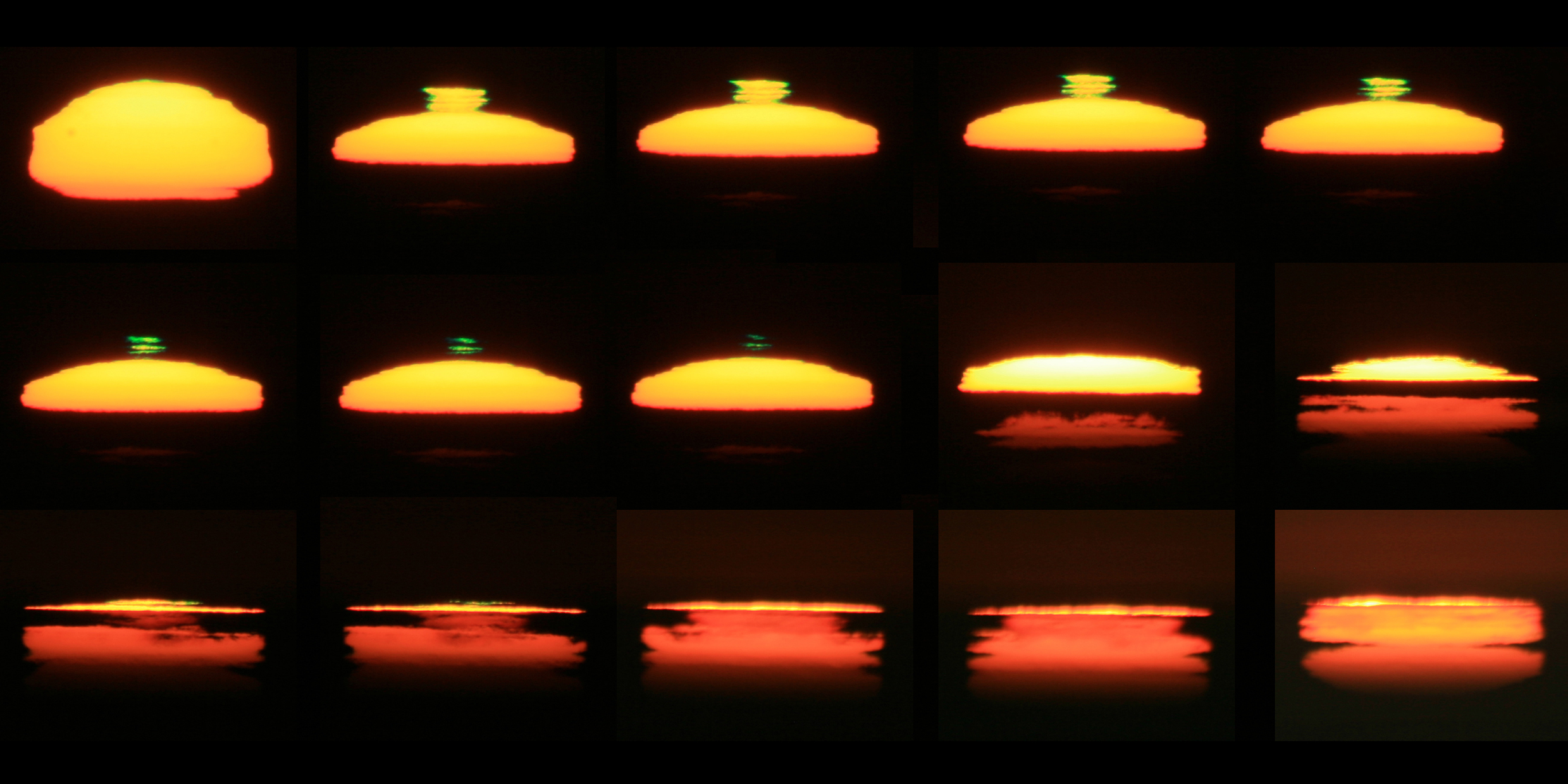

The green flash is a momentary blaze of emerald light that sometimes appears at the top of the sun’s disk as it sets behind a distant flat horizon. The flash is caused by refraction (bending) of sunlight as it passes through earth’s atmosphere. In effect, the atmosphere acts like a prism, spreading the sun’s light out into a series of overlapping colored disks, red at the bottom, blue at the top. Blue light is effectively removed from the spectrum by the great thickness of air we are looking through at sunset (which is why the setting sun appears red). When most of the red, orange and yellow light in the sun’s spectrum is blocked by the horizon we see what’s left — the flash of green.

By all reports, the effect is beautiful and electrifying.

Continuous search

I’ve looked for the green flash from all latitudes, north and south of the equator. I’ve looked over seas and deserts, from beaches and mountain tops. I’ve looked at sunrise too, for a rising sun can also produce a flash. I’ve watched thousands of setting and rising suns — with never a tinge of green.

Six years ago I mentioned my search for the green flash in a column. Several readers sent photographs. Others described observations of the flash from such unexotic venues as Cape Cod and the coast of Maine. One person invited me to his vacation home on a Caribbean isle where he claimed the flash was visible almost every evening (I didn’t go).

Sky & Telescope magazine frequently publishes photographs of the green flash supplied by readers, and one correspondent to the magazine reported seeing a mini-green flash from the planet Jupiter as it set behind a distant horizon.

So why haven’t I seen it? Just unlucky, I guess. But not a minute of the search was wasted.

Sunset and sunrise are the times of day when the sky puts on its most wonderful displays. The atmosphere empties its bag of optical tricks — reflection, refraction, absorption, scattering. Clouds go technicolor. Things high up catch the rays of the horizon-hidden sun, and so become visible. Satellites glimmer. Mercury and Venus make their appearances. Everything is there for the taking, including, if you’re lucky, the green flash.

Night and day, the sky is an every-changing theater of optical wonders. Mostly, however, we go around with our eyes to the ground. After all, the ground is where we eat, sleep, socialize, and make a living. If we look up at all, it is only to see the sky as a backdrop for airplanes, space shuttles, and pop flies to the outfield.

Learning to look up

Jack Borden, a Boston ex-newscaster, wants to change the way we look at the sky. Back in 1981 he founded a non-profit organization called For Spacious Skies with the goal of increasing sky awareness. It was Borden’s notion that we live our lives under a magnificent canopy, yet have reduced the sky to a kind of visual Muzak that hardly registers on our consciousness. The sky constitutes half of our visual field but mostly we keep our eyes cast down, says Borden. It’s as if half of what is available to our eyes is simply ignored.

Borden’s organization supplies educational materials to school children throughout the country and around the world. He has written a 32-page activity guide to help teachers incorporate the sky into the school curriculum. His goal is to use the sky to enhance students’ written and verbal skills, as well as improving their powers of observation.

By all accounts, For Spacious Skies has been successful at getting kids to look at something besides the television set. Admittedly, what they find in the sky is no longer of much practical importance. The day is past when the motions of celestial bodies and changes in the weather determined the cycles of human activities. What kids do obtain when they look upwards is esthetic, philosophical, perhaps even religious.

Our mammalian ancestors kept their noses to the ground in search of food or mates, or watching out for enemies. At some point, primates stood up on their hind legs and that at least got our eyes pointed towards the horizon. When we tipped our heads back and looked up to the sky we became fully human — religious, poetic, scientific, mathematical. Looking upwards we took our place at the edge of infinity.

Not a bad place to be — under spacious skies at the edge of the infinity, struck by beauty, humbled by depth, suffused with wonder. Not a bad place to sit and watch, year after unsuccessful year, for an ephemeral flash of green.