Originally published 12 October 1992

In mid-February 1493, Christopher Columbus’ ships, the Niña and the Pinta, neared the Azores on their return journey from the New World. The flagship, Santa Maria, had been wrecked on the shore of what is now Haiti, and Columbus had left some of his crew behind at a place he called Navidad.

A severe storm swept the little fleet, the worst the sailors had ever experienced. Fearing that his ships would founder, and that news of his voyage might be lost forever, Columbus wrote on parchment an account of his discoveries, wrapped it in waterproof waxed cloth, sealed it into a cask, and tossed it into the sea, in the hope that it might wash up on some European shore.

The ships survived the storm. The admiral made his report in person to his sovereigns, the King and Queen of Spain. The discovery of the New World became the central, transforming event of Western civilization.

As far as we know, the sealed cask was never found. What if the ships had gone down? The crewmen left behind at Navidad were slaughtered by Indians, so there was no chance that they might have somehow built a boat and returned to Spain. Columbus and his little fleet would have sailed into oblivion.

If Columbus had not returned, a chilling effect would have been cast over other would-be discoverers, and monarchs might have been reluctant to throw good money after bad. But two things made it inevitable that the discovery of America would not have been long delayed for long: the Geography of Claudius Ptolemy, and the invention of printing.

Scarcely anything is known of Ptolemy the man. He lived in the first half of the second century A. D., more than 13 centuries before Columbus. He seems to have done most of his scientific work at Alexandria in Egypt. He was a man of wide interests and orderly mind, who wrote books on geography, astronomy, music, and optics. That’s it. Remarkably little can be said about the man who made the discovery of America at the time of Columbus inevitable.

It is significant that Ptolemy lived at Alexandria. That city had long been a center for the study of the Earth and sky, and Ptolemy was heir to the accumulated knowledge of his predecessors. It was a place wonderfully suited for a geographer: Alexandria was a thriving commercial center, a gathering place for ships and caravans from all over the known world.

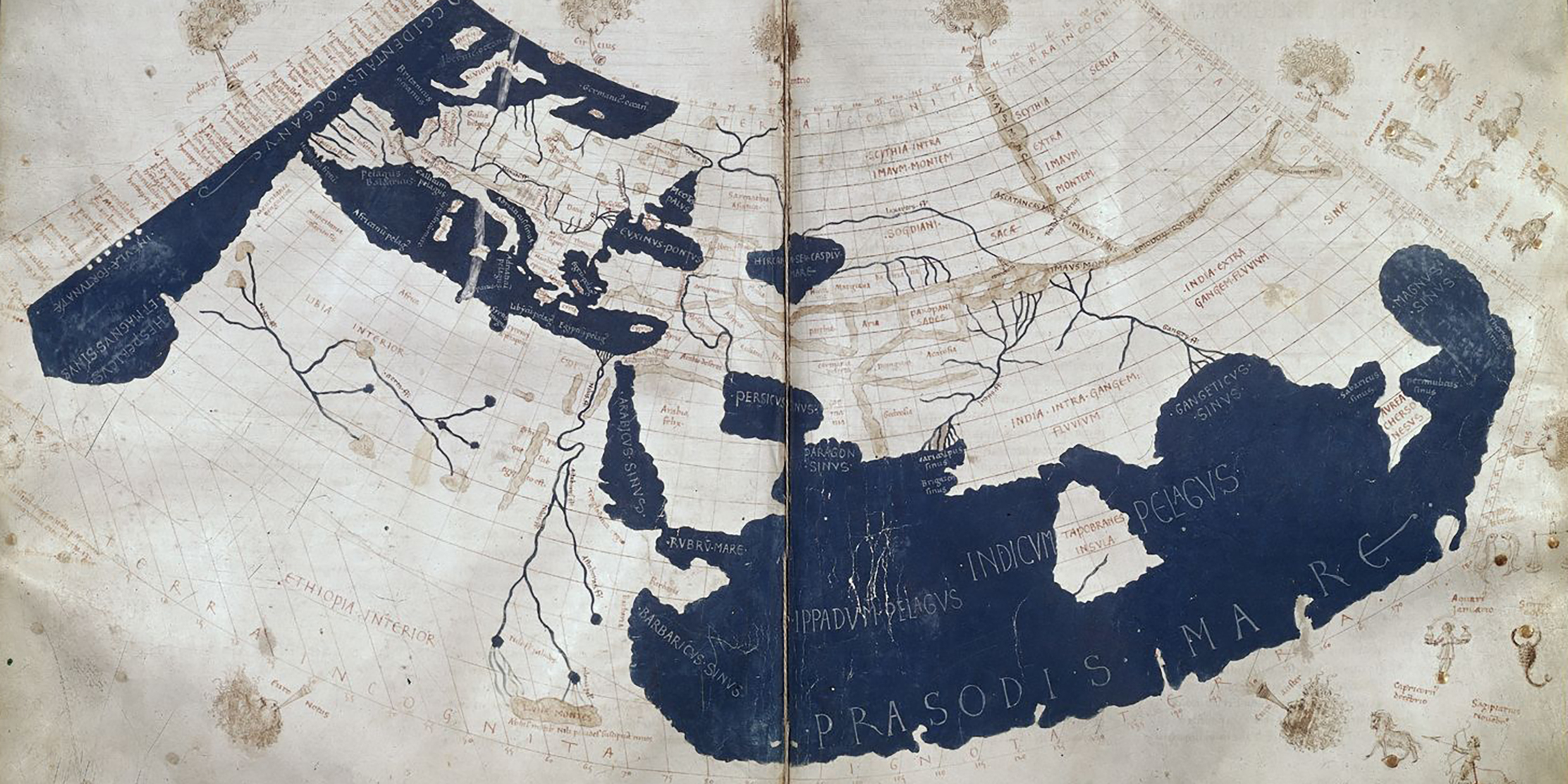

Ptolemy’s Geography consisted of an atlas of 27 maps, including a map of the known world, and extensive text. It is the only cartographical work to survive from antiquity. Almost every convention mapmakers use today, including lines of latitude and longitude, curved projections with north at the top, and ways of delineating the boundaries between land and sea, rivers, mountains, and towns, derive from Ptolemy.

Europeans learned of Ptolemy’s work from manuscripts imported from the eastern Mediterranean early in Columbus’s century. The first printed edition appeared in 1472, not long after the invention of printing by Gutenberg. Other editions quickly followed, and Ptolemy’s atlas became widely distributed throughout Europe.

The maps were a revelation. They fired imaginations. For the first time in a thousand years, Europeans held in their hands a vivid representation of a spherical earth. Columbus saw the maps of Ptolemy, and knew his destiny. If he had not returned from his voyage to the Indies, the maps assured that others would have followed soon.

How did Ptolemy’s maps survive, virtually unchanged, for more than a thousand years, in a time of hand-copied manuscripts. The answer, I think, has to do with what is Ptolemy’s greatest contribution to science — a contribution even greater than the maps that inspired Columbus.

Ptolemy was the first to describe the earth and sky without reference to human culture. His maps included none of the embellishments that found their way onto so many other representations of the world, before and after Columbus — no gods or goddesses, religious symbolism, kings and queens, ships, fish, or monsters. His goal was description, or as he called it, “saving the appearances,” with mathematical simplicity and as much fidelity to experience as possible.

His maps survived precisely because of their objectivity. They posed no threat to religious or political orthodoxies. They made no claim to Ultimate Truth. They were accompanied by instructions on how they might be amended as new experience warranted.

In all of this, Ptolemy was close to the spirit of modern science.

Medieval European maps placed Jerusalem at the center, and Eden (the East) at the top, with the continents laid out in the form of the cross of Christ. The only mountains delineated on some maps were Sinai and Calvary. Such maps had their purpose in the culture of their time, but they would hardly have inspired a mariner to set out across the western ocean.

Ptolemy’s maps inspired the confidence that made such a voyage inevitable. They were scientific in the best modern sense of the world. They presented a theory — of a spherical Earth of sailable dimension — that inspired a generation of Europeans. Columbus’s voyage can be thought of as a scientific experiment contrived to prove the theory.