Originally published 2 September 1996

DINGLE, Ireland — I watched as a tourist dismounted from a tour bus in Dingle town the other day. His video camcorder was glued to his eye as he came down the steps. Missed the bottom step and fell flat on his face.

The victim of this curious accident was more concerned about the state of his camera than his own well-being. Oblivious to his bumps and bruises, he seemed distraught that moments of his holiday were slipping away unrecorded. He shook the camcorder, peered through the viewer and tested the buttons until he was satisfied all was in order.

Off he walked with his tour-mates, camera to his eye, tape humming.

This was one of those little dramas that define a turning point in history. We have entered the age of electronic immortality.

Henceforth, when the body dies, the soul will live forever as a video recapitulation of a life. Pop in a cassette. Push “play.” It’s grandpa’s life. Everything he ever saw. Every birthday, every wedding reception, every holiday. Every stop on the coach tour of Ireland. Every…oh, look! Whoops! Here’s where grandpa fell in Dingle.”

The idea of electronic immortality was made explicit this summer when a researcher with British Telecom proposed the possibility of a “soul catcher” computer chip. Chris Winter is a scientist working on fusions of humans and machines — bionics and artificial life, that sort of thing.

He predicts that within 30 years it will be possible to implant a small but capacious computer chip behind the eye that will automatically record every thought and sensation in a person’s life, from cradle to grave.

“This is it — end of death,” gushed Winter at a press conference. “We envisage that all we think, all our emotions and creative brain activity will be able to be copied onto silicon. This is immortality in the truest sense — future generations will not die.”

Winter’s bizarre announcement was greeted with awe by the popular press, but it is just the natural extension of a trend that began with George Eastman’s invention of the cheap Brownie camera. For years we have been familiar with the tourist who hops off a tour bus, takes a snapshot of the local attraction — the Grand Canyon, say — then jumps back on the bus. It is not the scenery that evokes interest, but the mindless accumulation of snapshots, the paper record of a life. Kodak immortality.

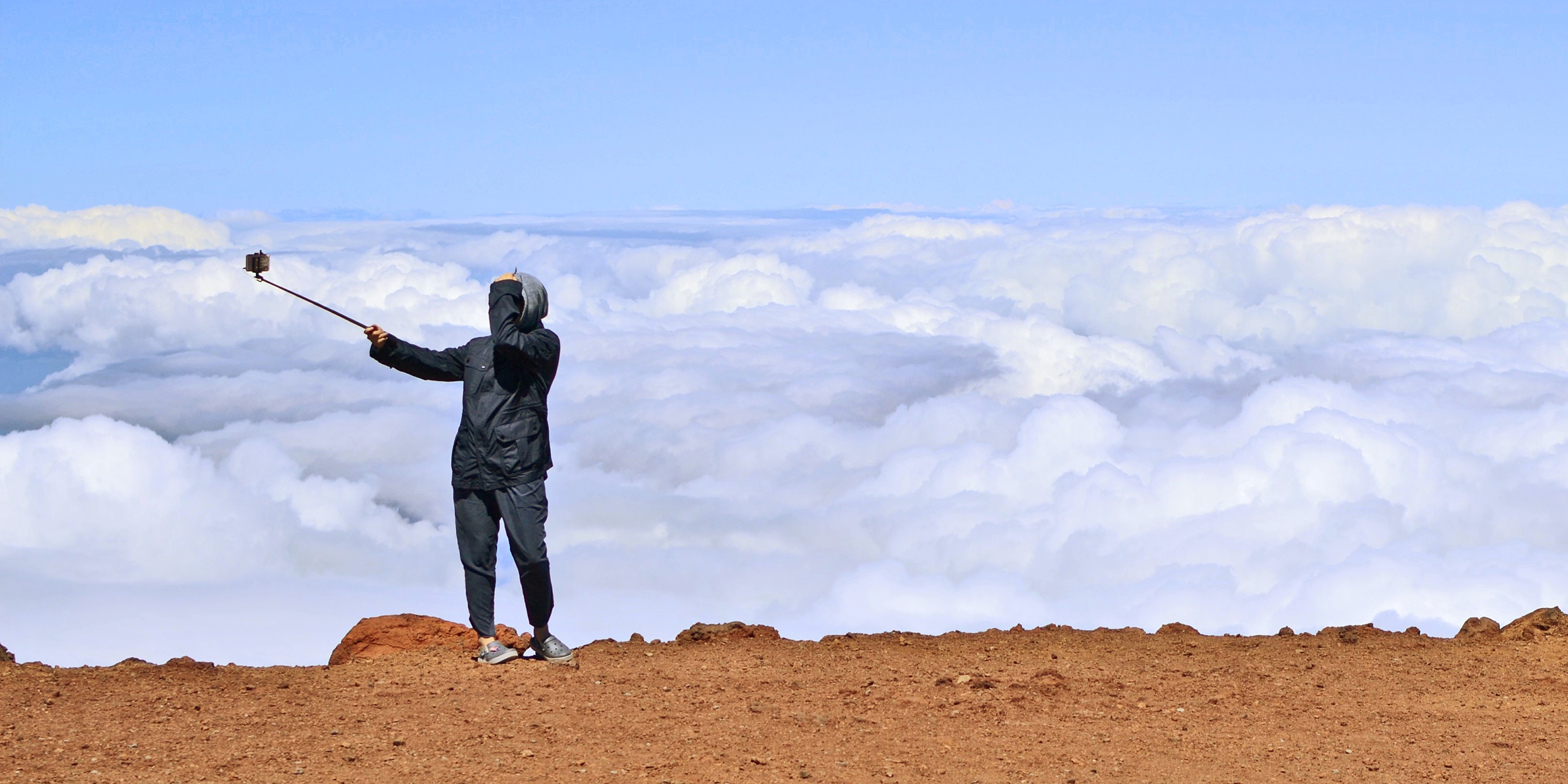

Today, the snapshot camera has been superseded by the camcorder. Busloads of tourists walk around Dingle town recording everything they see, including each other. Strange humanoid creatures with black protuberances sticking out from their heads, green and red LEDs flashing, motors gently whirring, bionic fusions of flesh and machine. They can hardly have observed anything with unimpeded vision.

Even little kids have camcorders these days. It cannot be long before every child of reasonably affluent parents will be given a video camera at birth. Learning to hold the camera to the eye will be as much a part of an infant’s training as learning to hold a spoon or use the potty. Nothing needs go unrecorded. With modest advances in data storage technology, an entire life as seen through the lens of the camera will easily be stored on a few tapes, disks, or chips.

There is an unnecessary duplication of optical systems, however. The camera lens focuses an image on an electronic photoreceptor, creating a series of electric impulses that are stored on tape. Meanwhile, the lens of the operator’s eye is focusing the same image onto the eye’s retina. One of these systems is redundant.

The solution is to insert electronic sensors directly into the optic nerves, along the lines suggested by Winter. The recording device itself might be implanted in the fleshy skin under the arm, with a pocket-like flap into which stamp-sized memory tabs can be inserted. Whatever passes before the eyes will be recorded directly, without need for a camera. The memory tabs can be popped out and played on a standard video screen, or filed away in a personal album called “The Afterlife.”

As science makes the disembodied soul increasingly untenable, it provides a sort of high-tech compensation. If the soul is nothing more than a crackle of electrons in the neurons of the brain, then there is no reason these signals can’t be stored in a silicon medium more permanent than mere flesh.

Chris Winter and his fellow researchers at British Telecom predict that by the year 2025 a single computer chip will have enough storage capacity to hold the thoughts and sensations of a lifetime, the equivalent of a library of 30 million volumes. Implanted at birth, the soul-catcher chip can be extracted at death, dumped into a computer, and watched on a video monitor by future generations.

No one at British Telecom seems to worry about the big question: If it takes a lifetime to watch a lifetime, then who will watch it? And if the watchers are themselves recording, then…oh, never mind.

Before you get too depressed by this loopy vision of silicon immortality, here’s a cheerier observation to think about. After witnessing the episode of the camcording tourist tumbling off the bus, I ambled out to the end of the Dingle Harbor pier. A young backpacker was sitting alone at the edge of the pier, lost in her own thoughts, jotting reflectively into her journal — not passively recording a life, but making one.