Originally published 15 February 1988

They are “the cosmically charged cornerstones upon which the great pyramids of Egypt were built.” They are “natural superconductors through which a universe of enlightenment passed to the lost continent of Atlantis.” They are crystals, and if you know how to use them they can make you healthy, wealthy, and wise.

Or so believe a growing number of New Age people, who use crystals in every aspect of their daily lives, often with horoscopes, herbs, incense, and elixirs. Beryl, for example, relieves stress. Diamond guards against envy. Azurite heightens dreams. Garnet improves self-esteem. And good old white quartz is an energizer, channeling into your environment the very best of cosmic vibrations.

Bookstores are full of crystal self-help books, or you can pay $75 an hour to visit a crystal consultant. We knew crystals had made it big when a few months ago they appeared on the cover of Time, in the hands of New Age guru Shirley MacLaine.

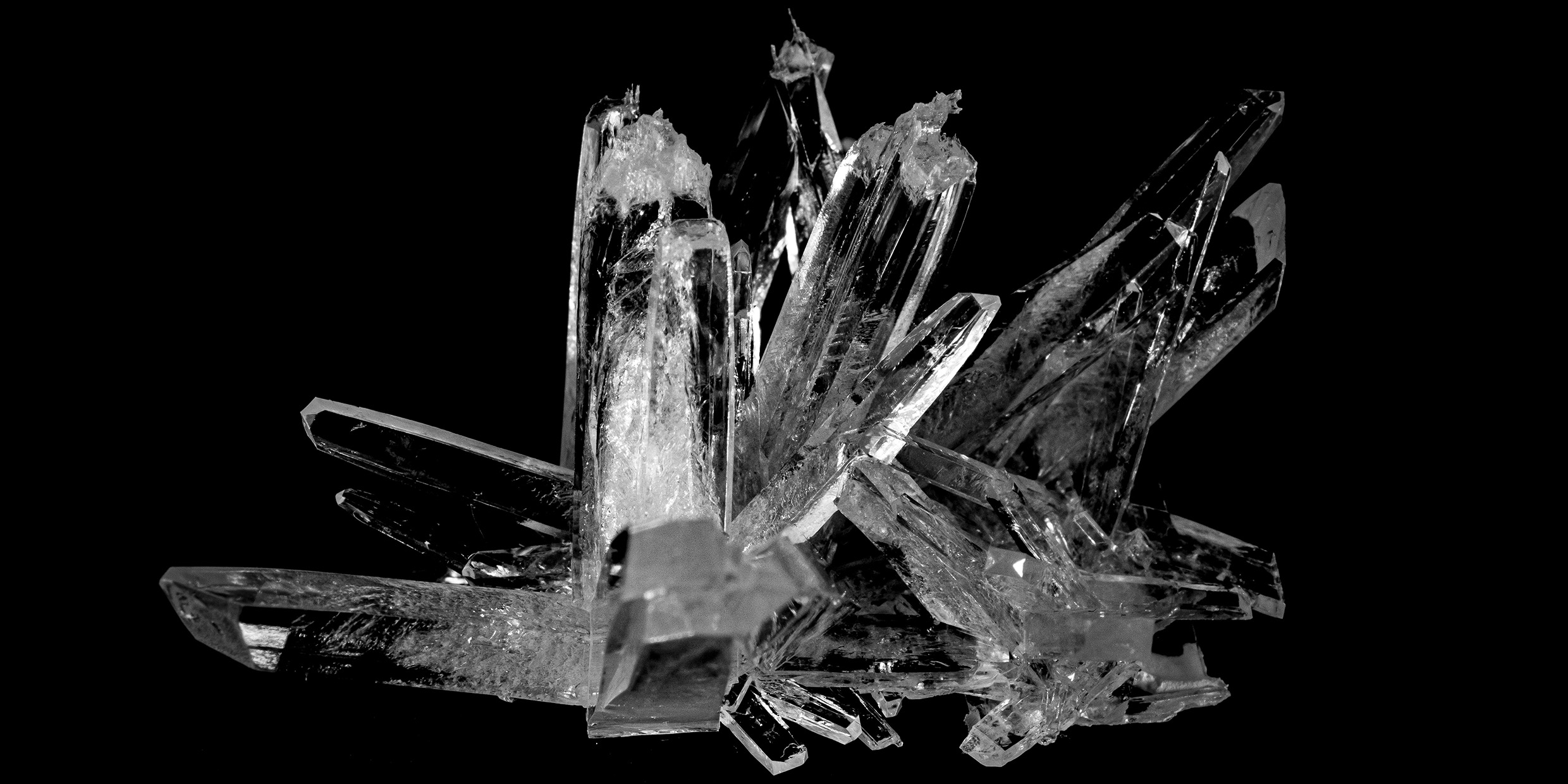

Now it so happens that I have on my desk a cluster of quartz crystals almost identical to those on the Time cover. And, as a matter of fact, a number of good things began happening in my life at about the time I got the crystals.

Have I become a New Age believer?

The delight of patterns

Stephen Jay Gould once wrote that “the human mind delights in finding pattern — so much so that we often mistake coincidence…for profound meaning.” Science is one highly successful apparatus for winnowing the wheat of profound meaning from the chaff of coincidence. And in the matter of crystals, I’ll stick with science.

The coincidence between my crystals and my good fortune was just that — coincidence. Yet the crystals are on my desk for a profound reason, and the reason is delight in pattern.

Crystals are windows on the world of atoms. Perhaps better than anything else in our natural environment they exemplify the patterns of order that are built into nature on the atomic scale.

The quantitative science of crystals began in the 17th century when the Danish natural philosopher Nicolas Steno noticed that the faces of quartz crystals always meet at the same angle. No matter how big or small the crystal, or its shape, or its place of origin, the angles are the same.

While I was writing this piece, I put my cluster of quartz crystals under a microscope and entered a world of spectacular architectural forms — gorgeous, icy-smooth planes colliding this way and that to form a space-age city of towering pillars and plunging chasms. And at every edge, Steno’s unvarying angle of 120 degrees. A hint of constancy in the midst of chaos.

In the late 18th century, the mineralogist René Just Haüy made another remarkable discovery about the nature of crystals. According to the story, Haüy was examining a large calcite crystal in the home of a friend when he dropped it. To his embarrassment, it shattered. When he stooped to pick up the pieces he noticed that every fragment, large and small, had the same basic shape as the original crystal. “Tout est trouvé!”, shouted Haüy — “All is discovered!”

Hauy rushed back to his lab and smashed a calcite crystal into tiny bits, and every piece resembled the parent. He reasoned the the smallest units of the crystal — perhaps even on the atomic scale — would have the same shape.

Lovely imperfections

In the 20th century, X‑rays confirmed Haüy’s conclusion. The shape of a crystal is determined by the way atoms of that substance bind together to form “lattices” — repeating arrays of space-filling atomic units. In all of nature there are only a few classes of fundamental crystal shapes, and these can be predicted mathematically. Yet no two crystals are exactly alike, and that too is part of their attraction.

Tiny traces of impurities add color to crystals — emerald, sapphire, ruby, aquamarine. Pure quartz is clear; the amethyst color of my quartz cluster probably derives from tiny traces of iron, and this departure from perfection enhances the beauty and value of the crystals.

Under the microscope my apparently regular quartz crystals become a showcase of imperfections — color variations, striations, cracks, and inclusions, including some wonderful “starburst” crystals of goethite (if my guess is right) embedded within the quartz — patterns within pattern.

All of this beauty hints at things still beyond the crystallographer’s ken. Most mysterious of all is the riddle of crystal growth. If crystals grow by adding atoms at the surface, and if atoms fall into place essentially at random, then why aren’t those shimmering surfaces that I see in my microscope bumpier?

And consider the perfect symmetry of the snowflake? How do atoms attaching themselves at one tip of the growing six-sided crystal know what’s happening at another tip? The answer may have something to do with vibrations within the crystal, vibrations of exquisite sensitivity that maintain a delicate — dare I say cosmic — balance between order and disorder.

Are the crystals on my desk channeling those cosmic vibrations into my personal life? I think not. Crystals are delightful icons of design in nature, but the New Age wheat of profound meaning is my chaff of coincidence.