Originally published 19 December 2004

Galileo, OrbView‑2, Terra, Aqua, Lunar Orbiter, Magellan, Mariner 10, Yohkoh, SOHO, TRACE, Mars Pathfinder Lander, Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey, Viking Orbiter, Viking Lander, NEAR, Cassini, Voyager 1 and 2.

These are the Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria of planetary exploration, tiny machines, smaller than Columbus’s craft, hurled into space with cameras and remote sensors. None has returned home. Their equivalent of Aztec and Incan gold was beamed back to Earth as radio streams of binary data. A few have left the solar system and now drift into the space between the stars.

And where is this “Aztec and Incan gold,” the glorious booty from new worlds? It is stored in NASA computers. Much of it is available on the internet, if you know where to look for it. Most of it would mean exactly nothing to most of us.

But let me make a recommendation. If you buy one coffee table book this year, let it be Michael Benson’s Beyond: Visions of the Interplanetary Probes. Benson has searched space-probe archives for the most spectacular photographs of the objects in our solar system, including the Sun, Moon, and Earth. Here is treasure in abundance, beauty and knowledge fit for a king or

queen.

And not just knowledge of barren planets and cratered moons. Self-knowledge too. We cannot know ourselves unless we know the universe that gave us birth. Nietzsche said that humans are a rope stretched between the animals and the gods — a rope across an abyss. The robotic planetary explorers are rope.

We are the creatures who invented these magnificent machines, who chose to invest out wealth in ships that would return not with silver and gold, but with pure knowledge. Knowledge of the planets. Knowledge of ourselves.

The great bulk of what we paid for never even made it into space. Propellant, booster shells, discarded second and third stage rockets, and tons and tons of fuel and hardware goes nowhere. Its only purpose is to lift a package of cameras and sensors out of Earth’s gravity. And without Earthbound computers, radio receiving stations, and control rooms the planetary robots would be deaf and blind.

I’ve seen some of Benson’s photographs before, in science publications, on the websites for the individual projects, or one-by-one in the media. But to see them all together, reproduced in high quality, digitally enhanced, on glossy paper, is a mind-blowing experience.

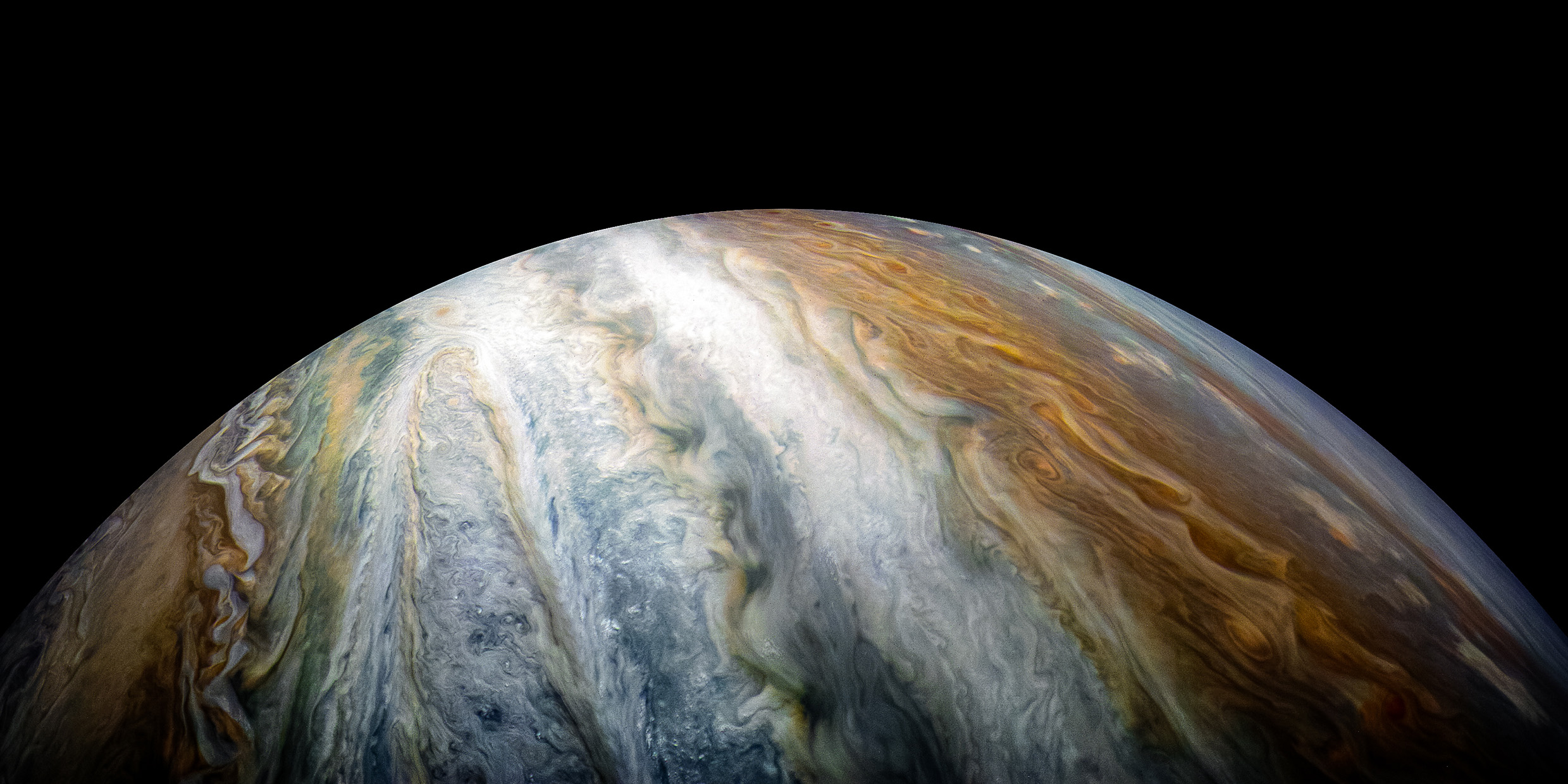

Among my favorite images: Northern Canada and Greenland from high above the North Pole; a four-page fold-out spread of the cratered lunar surface, battered, as was the early Earth, into pits and dust; solar storms as seen in x‑rays and ultraviolet light; defrosting dunes on Mars; asteroid Ida and its tiny moon Dactyl; Jupiter’s moons Io and Europa against the backdrop of the planet’s psychedelic surface; a volcano erupting on Io; pop-art images of Saturn’s rings; the dual crescents of blue Neptune and its moon Triton.

But why am I making choices? There is not an image in this book that is not worth savoring.

This morning, the latest issue of Science arrived, with a special section on the Mars Opportunity rover, replete with photographs of Opportunity’s tracks in the Martian dust, and the round depressions in Martian rocks where Opportunity has tasted minerals.

This robot, like the ones featured in Benson’s book, is an extension of our own senses — seeing, sniffing, tasting, touching an alien landscape.

Eleven articles in Science cover every aspect of the Martian surface and atmosphere. Several hundred authors altogether; the names read like a roll call at the United Nations: Yen, Klingelhofer, d’Uston, Calvin, Wdowiak, Arneson, Guinness, Rodionov, Chu, Anwar, Ghosh, Spanovich, Smith, etc. No way to tell the religion or politics of the authors; planetary exploration is an activity that transcends the squabbles that fragment our own tiny planet.

The photographs in Beyond take us beyond our squabbles, show us a universe ruled by natural law, teach us just how fragile and precious life is.

On the last page of the book, Benson quotes a sentence from a NASA press release about an earlier Mars rover: “The health and status of the rover is unknown, but it is probably circling the vicinity of the lander, attempting to communicate with it.”

An extraordinary sentence. That little rover on the lifeless planet, an artifact of our quest for reliable knowledge of the world, trying its best to phone home.