Originally published 2 January 1989

Lots of stories in the news lately about the perils of mega-technology.

Monstrously expensive nuclear reactors at Seabrook, N.H., and Shoreham, Long Island, continue to sit idle. The cost of the Shoreham plant has soared 70 times over the original estimate, and now, after 22 years of planning and construction, some experts believe the best plan is simply to abandon the plant.

Three B‑1 bombers have crashed in the past 16 months; the $280 million plane is so technically sophisticated it seems to have a hard time staying in the air. And, of course, there’s the astronomically expensive Strategic Defense Initiative — Star Wars — a missile-defense scheme of such overwhelming complexity that many critics believe it can never work.

Rube Goldberg, where are you now that we need you?

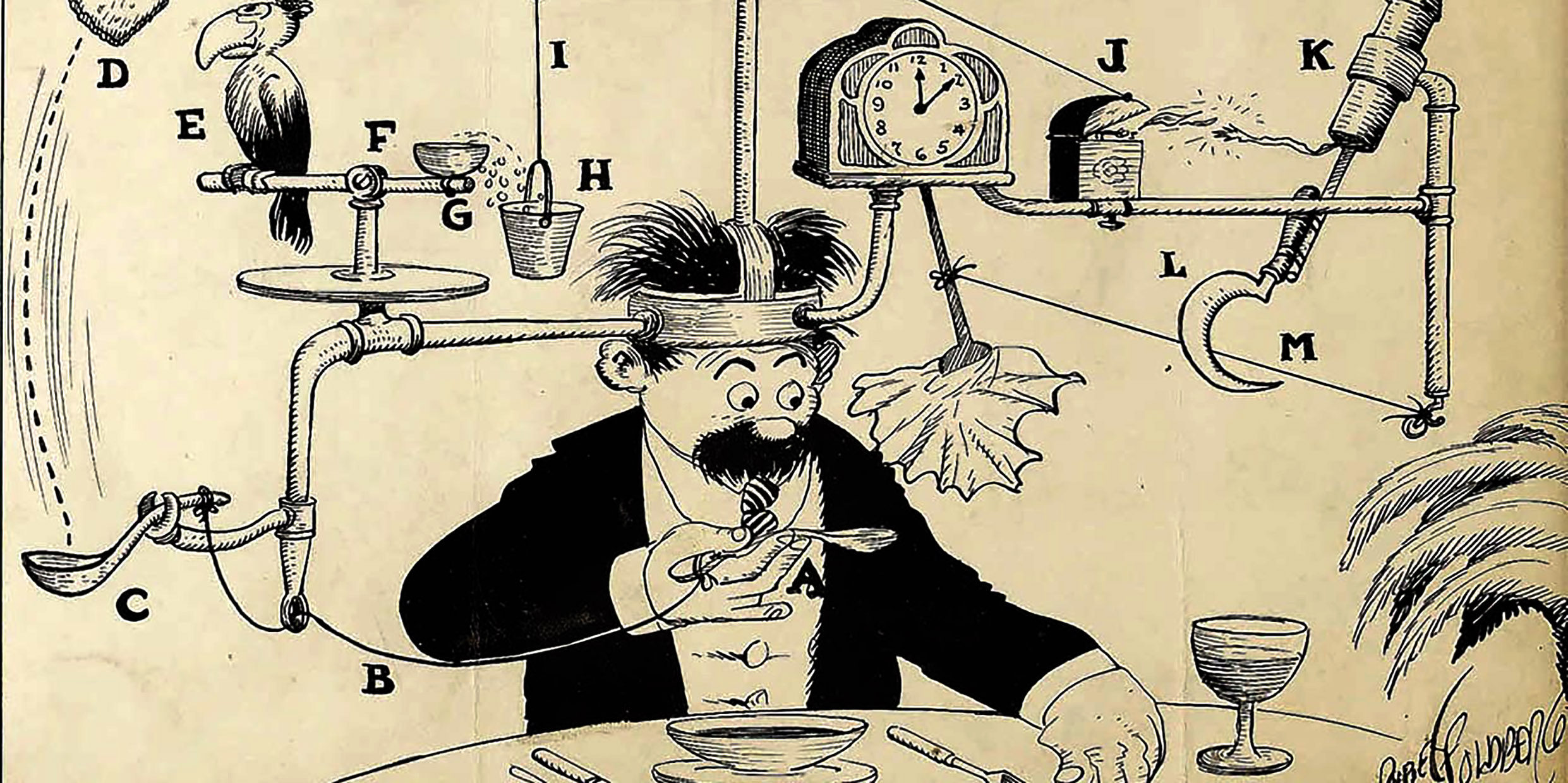

Goldberg was our philosopher of technical excess. His loony inventions, widely published in American newspapers from 1914 – 64, helped keep our technological exaggerations in perspective. He is the only American to have his name become a dictionary word while still alive.

A “Rube Goldberg” invention uses a ridiculously complicated mechanism to achieve a simple result. Every engineer or technical planner with responsibility for more than a million dollars of public money should be required to read the complete collection of Goldberg’s cartoons.

Lap savers and button finders

Consider Goldberg’s “Simple Way to Open an Egg Without Dropping It in Your Lap.” When you pick up your morning paper an attached string opens the door of a bird cage. The bird exits, follows a row of seeds up a platform, and falls into a pitcher of water. The water splashes onto a flower and makes it grow, pushing up a rod attached by string to the trigger of a pistol. The report of the pistol scares a monkey, who jumps up, hitting his head against a bumper, forcing a razor into the egg. The egg drops into an eggcup, and the loosened shell falls into a saucer.

Or how about “The New Household Collar-Button Finder.” A man seeking his lost collar button plays “Home Sweet Home” on the oboe. A homesick goldfish is overcome by sadness and sheds copious tears, which fill the goldfish bowl and cause it to overflow onto a flannel doll. The doll shrinks, pulling a string attached to the power switch of an electromagnet. The magnet attracts an iron dollar attached to a thread, lifting a cloth that covers a still-wet painting of a dog bone. The dog licks the bone, gets sick from the paint, and goes looking for relief. He mistakes the collar button for a pill. When his teeth strike the hard brass button he gives a howl, alerting the man to the location of the missing item.

Goofy inventions like these entertained two generations of Americans and kept us aware of our propensity for technological overkill. With zany good humor, Goldberg showed us how to laugh at our foolishness. If a Rube Goldberg didn’t exist, we would have needed a Rube Goldberg to invent him.

The modern dilemma

Goldberg took a college degree in engineering, but cartooning was his life. His biographer, Peter Marzio, tells us that “despite his constant grumblings against the automatic life, Rube loved complex machinery. He marveled at its labor-saving potential, its rhythm, and even its beauty. But he also treasured simple human values and inefficient human pastimes such as daydreaming and laughing.”

Like most Americans, Goldberg loved and hated machines. According to Marzio, he was keenly aware of the modern dilemma: How can mechanization be introduced and used without demolishing the life-giving harmony between man and his environment?

Goldberg knew that technology grows unwieldy because of our insatiable desire for the very latest inventions, at whatever the cost in money or frustration. He imagined an army of “Yokyoks,” tiny green men with long, straight noses and red-and-yellow gloves, who carried an assortment of tools and went about fouling the works — clogging holes in saltshakers, making pens and faucets leak, blowing fuses, letting the air out of tires. Goldberg warned us against the “gadget strewn path of civilization.” The more complicated our machines become, the more opportunities the Yokyoks have to drive us crazy.

We have no shortage of contemporary doomsayers who rail against the invidious influence of technology in our lives. Rube Goldberg’s critique of technology was effective because it betrayed his unabashed affection for machines, while at the same time exposing their troublesome costs. He did not wish to see the technical apparatus of modern civilization dismantled; he merely wanted to make room between the cogs for a little human fun.

Goldberg’s inventions, for all their bizarre exaggeration, served simple human needs, usually things ignored by the overblown schemes of government and industry. Finding a lost collar button. Removing lint from wool. Getting gravy spots off a vest. Preventing cigar burns on carpets. And Goldberg didn’t require megawatts and megabucks to accomplish his tasks. His machines employed rabbits, spaniels, old shoes, firecrackers, banana skins, frogs, string, umbrellas, leaky fountain pens, cheese, balloons — his technological arsenal was the stuff of yard sales.

Rube Goldberg died in 1970 at the age of 87. If he were still alive, we could ask him to design a cheaper replacement for the Seabrook and Shoreham plants, the B‑1 bomber, and the Star Wars defense system. A good laugh at the result might help us find our way out of the quagmire of mega-technology.