Originally published 2 February 1998

Spacecraft Galileo, a 2½-ton hunk of human ingenuity, has been orbiting Jupiter since it arrived there in December 1995 after a six-year voyage from Earth. The craft is moving on an egg-shaped orbit that takes it close to Jupiter, then out beyond the orbits of its four big moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

In about a week’s time, it will make a close encounter with Europa, and we will again be afforded a view of that moon’s icy surface.

For two years, the spunky spacecraft has been chalking up encounters with Jupiter’s moons, and the mission is not over yet. After the approaching flyby of Europa, the spacecraft will pay four visits to Callisto, then make a close call on Io.

Jupiter’s moons! These mysterious worlds have excited human imagination since Galileo Galilei first spied them through his telescope in the winter of 1610. At first the great Italian astronomer thought he was viewing tiny background stars, coincidentally lined up beyond Jupiter. Then, as evenings passed and he returned again and again to look at Jupiter, it dawned upon him that the planet had four satellites moving about it in circular orbits.

The discovery was electrifying. Revolutionary. Here was proof that Earth was not the sole center of cosmic motions. Nor, for that matter, was the sun. The universe had a multiplicity of centers, and we, poor humans, did not stand upon the central stage.

It was a discovery that did not endear Galileo to his contemporaries. We know the outcome of the story: How the old, nearly blind astronomer was forced to kneel before assembled churchmen in Rome and deny what he knew to be true. Those four dancing specks of light in the eyepiece of his telescope bore a message that most humans simply did not want to hear.

Four hundred years have passed, and the old man gets the last laugh after all. His name is now attached to a spacecraft that has navigated hundreds of millions of miles for a close look at what we now call Jupiter’s “Galilean” moons.

Most of us have gotten used to the fact that we are not the be-all and end-all of creation, but NASA press releases and media reports about the Galileo mission still emphasize the strange natures of Jupiter’s moons, almost as if the PR people and journalists know that we still want to distinguish ourselves from the rest of the universe.

But the real story from the Galileo mission is that the moons of Jupiter are very ordinary indeed.

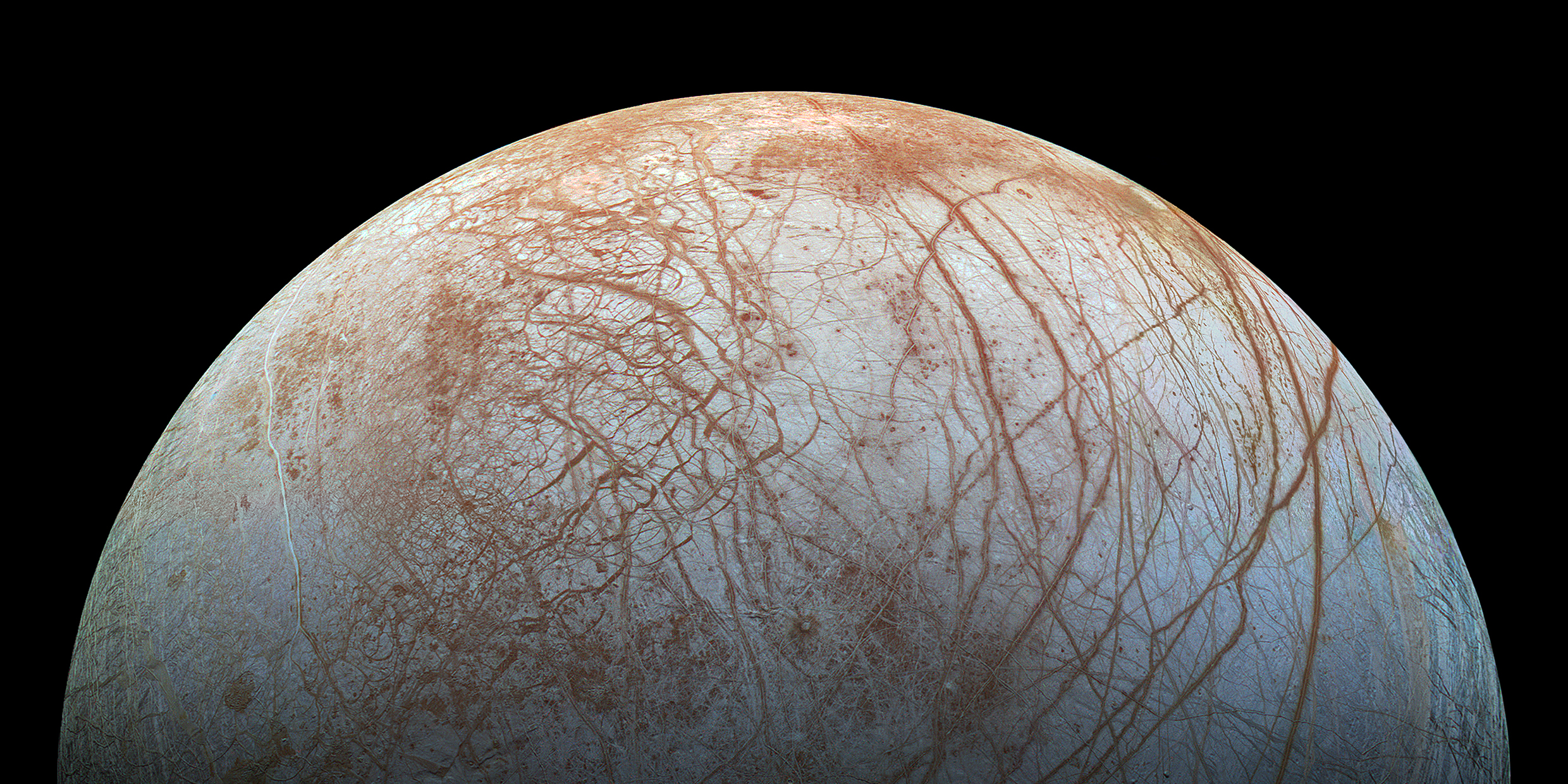

Consider Europa, the second Galilean moon from Jupiter, about the same size as our own lunar companion. The Galileo spacecraft has made a stunning photographic map of its surface. And from the gravitational effect of Europa on the motion of the spacecraft, scientists can calculate the moon’s density and something of its mass distribution.

What do we find? That Europa has a metallic core and an overlying rocky mantle. The rock is covered with a water ocean, frozen solid on the surface.

The moon’s interior is kept hot by the tidal flex of Jupiter’s gravity, the way a piece of metal is made hot by repeated bending. The rocky mantle may be hot enough to move in convective loops, like boiling water in a pan, perhaps generating volcanic activity on the ocean floor, exactly as on Earth.

Photographs show a surface of fractured ice, like Earth’s frozen Arctic Ocean. Some of the surface is pale icy blue; other parts are reddish brown, perhaps dusted with mineral contaminants from below.

Most surprising of all, considering its feeble gravity, Europa appears to have an atmosphere. Scientists have detected a distortion in the radio signal from the spacecraft caused by an ionosphere of charged particles near Europa, which implies a gassy envelope for the moon.

Metallic core, rocky mantle, frozen water ocean, volcanoes, atmosphere: It’s all breathtakingly familiar. Take the planet Earth, shrink it in size, put it into orbit around Jupiter, and you’d have something remarkably resembling Europa.

And just as Europa is like a little Earth, the system of Jupiter’s Galilean moons is like a little solar system.

Innermost Io is churned by tidal friction and made fiercely hot, the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Photographs show gas plumes rising from volcanoes.

Ganymede, third from Jupiter, is cooler than Europa, with a surface of cross-hatched water ice.

Outermost Callisto is coolest of all, with no surface evidence of geological activity within.

It all looks wonderfully commonplace. And that’s the big story from the Galileo spacecraft: That the universe holds few surprises. Our little corner of the cosmos is typical, and the science we have learned here applies in other worlds as well.

Old Galileo Galilei, on his knees in Rome, was forced to mumble the recantation, but he knew he was right. Those specks of light in his telescope orbited another center. The Earth was not unique.

He was more right than he knew.