Originally published 4 May 1998

Author Doris Lessing began her sci-fi chronicle of space with this dedication: “For my father, who used to sit, hour after hour, night after night, outside our home in Africa, watching the stars. ‘Well,’ he would say,‘if we blow ourselves up, there’s plenty more where we came from.’ ”

Oh, there’s plenty more, all right; stars spangle the sky in uncountable numbers. And they’re blowing up all the time.

The biggest stars live fast and die young in explosive events called novas and supernovas. The stars we see with our unaided eyes tend to be among the most massive and most luminous, and are therefore good candidates for a big bang.

But human life is short compared to the lifespans of even the most short-lived stars. Lessing’s father, in a lifetime of watching the sky, would be unlikely to see more than a few dying stars blow up. In my lifetime, I have seen only one stellar eruption, the nova of August 1975, which for one glorious evening blazed almost at bright as the nearby star Deneb in the constellation Cygnus, like a feather plucked from the swan’s tail.

The most famous supernova of recent times was visible to the unaided eye for a few months during the first half of 1987, but only for observers south of the equator. This was a very big bang as stellar explosions go, but it was rather far away, in a small companion galaxy of the Milky Way, and never became bright enough to dazzle the backyard skywatcher. Eleven years later, it continues to put on a show for telescopic observers, as the star’s remnants race outwards, colliding with the debris of previous, less violent outbursts.

On almost any clear night, a persistent telescopic astronomer might observe a faint supernova in some distant galaxy. A blowup can be expected in a typical spiral galaxy a couple of times a century. The last supernovas on our side of the Milky Way Galaxy happened in 1572 and 1604, which means we are overdue for spectacular fireworks.

The 1572 event is called Tycho’s Supernova, after the great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who demonstrated conclusively that the bright new object was among the “fixed stars,” and that therefore Aristotle’s “immutable” heavens were subject to change.

Tycho’s protege Johannes Kepler observed and wrote about the supernova of 1604, which stimulated yet more public interest in all things celestial and gave a boost to the new sun-centered system of Copernicus.

Both supernovas were brighter than any star in the sky, and remained visible for months. Today, we turn our telescopes to the places in the heavens where the two “new stars” appeared and we see tatters of shattered starstuff.

The Milky Way Galaxy is littered with dead and dying stars wrapped in colorful shrouds of expelled matter. In recent years, the Hubble Space Telescope has photographed a spectacular gallery of stars in their death throes, puffing off layers of their substance or blowing themselves to smithereens.

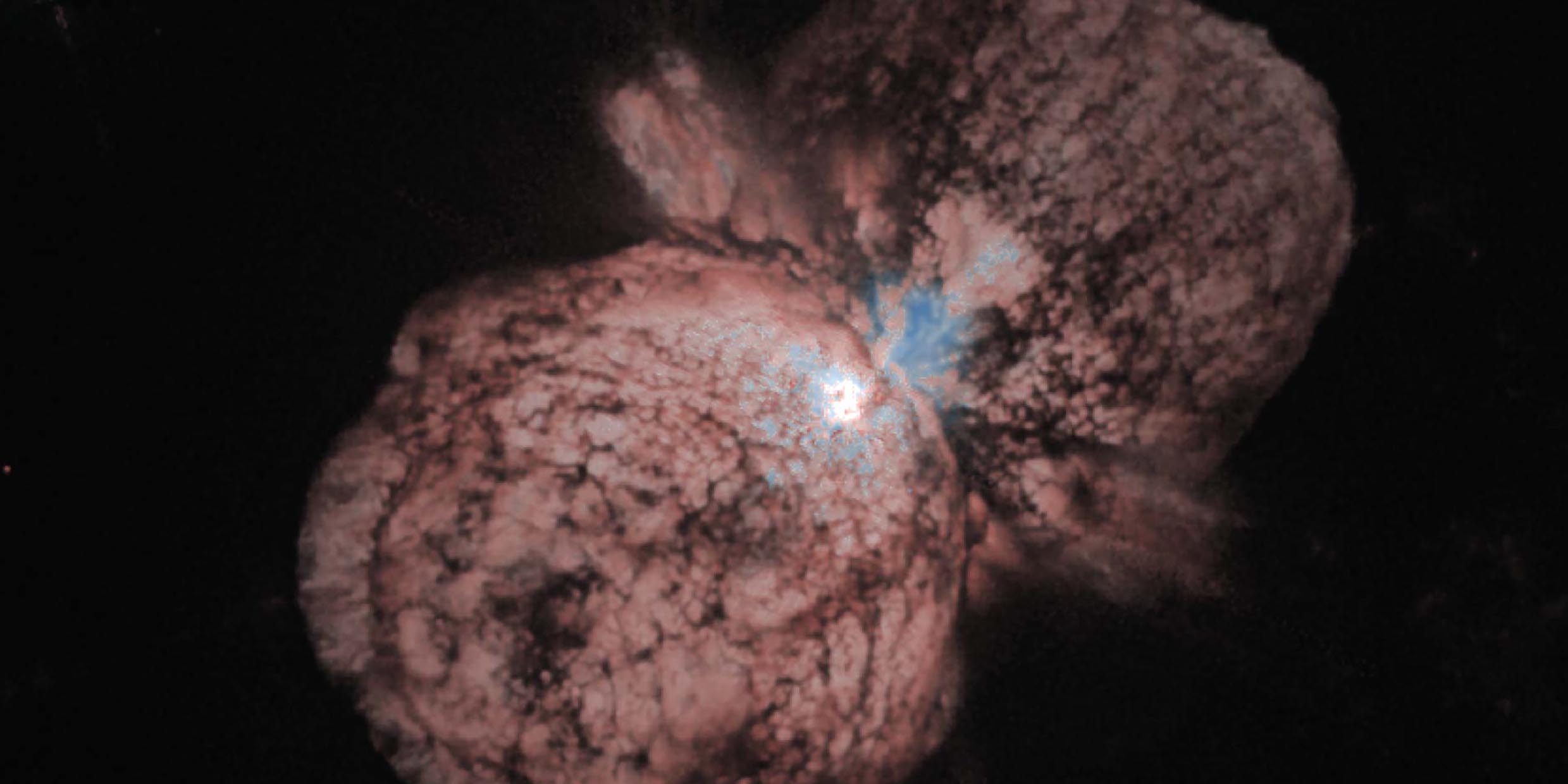

Perhaps the most dramatic Hubble image of a dying star is the supergiant Eta Carinae, 7,500 light-years away and one of the brightest and most massive stars we know about in the universe: 4 million times more luminous than the sun and 100 times more massive. Eta Carinae is ripe to become a pyrotechnic wonder.

About 150 years ago Eta Carinae underwent a mammoth convulsion, blasting out two symmetric lobes of matter weighing as much as several suns. The star (or perhaps it is two stars in a binary system) survived mostly intact, but the flare-up may foretell more dramatic things to come.

The Hubble photograph of Eta Carinae evokes terrific violence. The seething globes of ejected matter are expanding at hundreds of miles per second. Each of them bears a striking resemblance to the fireball of an atomic bomb explosion, although on a vastly different scale. Each of the star’s fireballs is presently 10,000 times bigger than our solar system.

Eta Carinae is about three times closer to Earth than the stars that blew up in 1572 and 1604, so it promises a spectacular show if it goes supernova, brighter in our sky than Venus at its brightest.

Most stars that are likely candidates for supernova are far enough away to present no danger to Earth, so for the time being we can enjoy the beauty of the Hubble photographs without undue worry about being caught up in the trauma of star-death.

Scientists believe supernova explosions are forges for creating heavy elements. Every carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atom in our bodies was probably created in supernova explosions of stars that lived and died in the Milky Way Galaxy long before the Earth was born. If so, then we can look at the unleashed fury recorded in the Hubble photographs and know that these violent star-deaths are necessary to seed the universe with the elements of life.

These terrible and beautiful remnants of exploded stars are indeed “where we came from.”