Originally published 1 March 1993

Gather round, children, and listen to my tale of coming of age in the Milky Way.

When I was your age, we thought ourselves citizens of the Solar System. The sizzling surface of Venus, the icecaps and canals of the Red Planet, Saturn’s air-wrapped moon Titan: these were the outermost horizons of our imaginations.

Whatever existed beyond Pluto — those thousand billion stars in the whirling disk of our Milky Way Galaxy — were too remote, too vast, to comprehend. The Milky Way was the threshold of infinity.

But — ah! — within the precincts of the Solar System we found room enough for adventure. We visited the crystal palaces of Jupiter’s moons. We met and mated with beautiful, green-skinned aliens from Planet X. We fought off refractory Vesuvians intent upon the colonization of Earth.

And, at last, we sent spacecraft called Mariner, Viking, Voyager, and Magellan on journeys of discovery to every planet (save one) that circles the sun.

It’s old hat now. The Solar System is terra cognito. The rings of Uranus are as familiar to us as our own backyards. Mercury’s sun-baked face is a bore. But that is as it should be. We are old now. It is time for a new generation to look into space.

Your generation.

Astronomers are blazing the way beyond the yawning gulf that separates the Solar System from our neighboring worlds. With fabulous new telescopes, they are mapping the thousand billion stars. You, my children, will be citizens of the Milky Way.

Computers, too, are telescopes of sorts. They allow astronomers to calculate the dynamics of gas and stars in faraway regions of the Galaxy; the results of the calculations can be compared with observations, allowing astronomers to turn static observations into history.

Imagine, children, a journey to the center of the Milky Way, a place hidden forever from our visual inspection by the dust and gas that fill the space between the stars. Radio waves and X‑rays penetrate the mists, revealing…

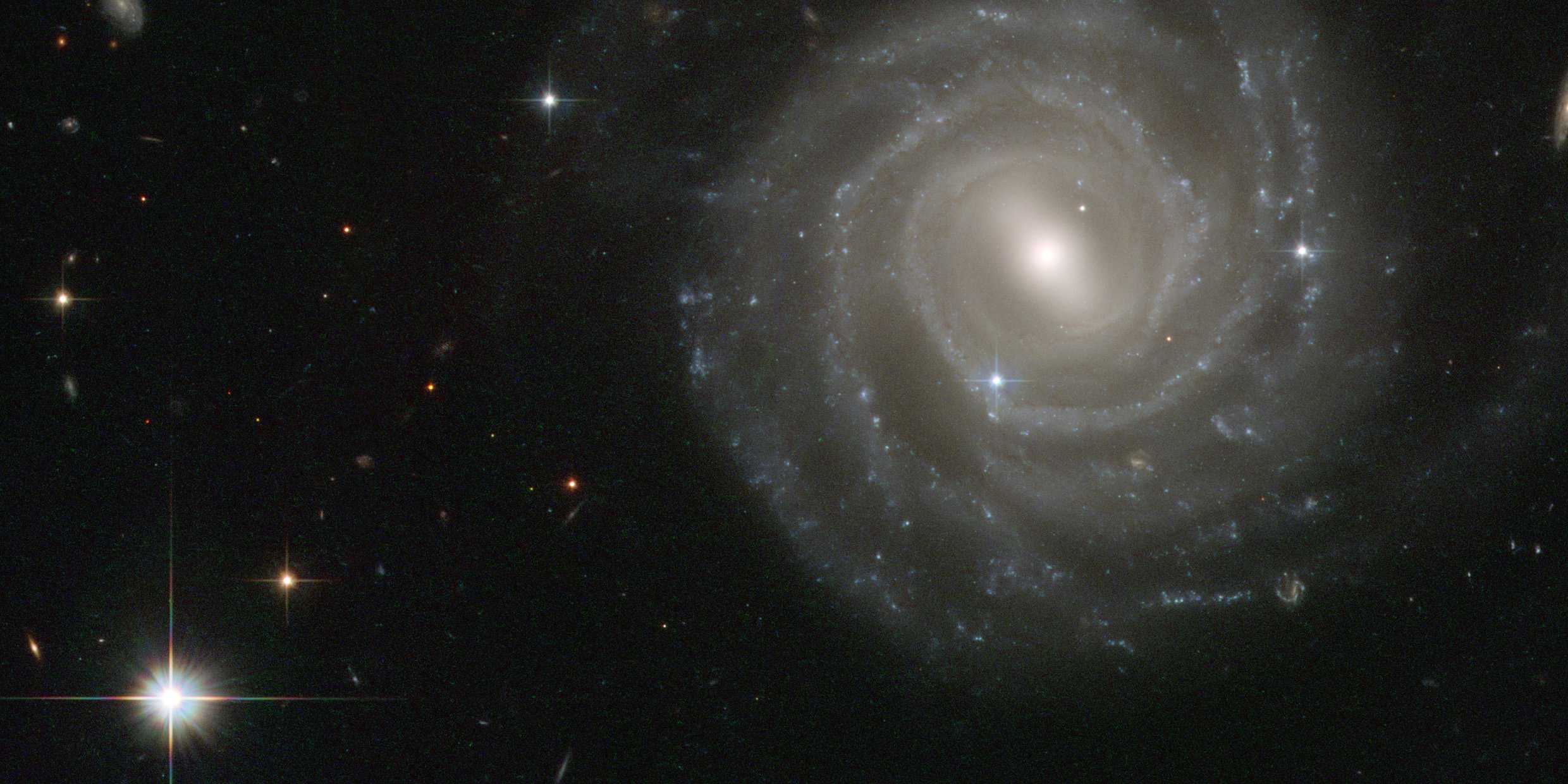

We used to believe that the Milky Way was a normal spiral galaxy, with starry arms pinwheeling out from the very center. But no! It is a barred spiral. Two spoke-like arms extend straight out from the center of the Galaxy on opposite sides, then bend to wrap their way to our neighborhood some 30,000 light-years from the center.

The rotating bars pump gas towards the center of the Galaxy — this can be calculated with computers and observed with telescopes. Monstrous clouds of gas fall inwards along a sequence of wildly dancing orbits, colliding, shaking off energy, shining with a fierce invisible light.

Now we approach the central bulge or nucleus of the Milky Way, a region as small compared to the Galaxy as a grapefruit seed at the center of a dinner plate. Here the pressure of the gas builds, as if in a pressure cooker, until it explodes — schoosh! schoosh! — in bursts of outrushing wind.

One might think that with so much gas at such high pressure, stars would spring prodigiously into existence, for it is out of the interstellar gas that stars are born. But the rate of star formation in the nucleus is modest. The violence, the stirring, the intense magnetic fields, inhibit gravity from gathering together the stuff of new stars.

As we draw closer to the center — to the pinpoint at the center of the dinner plate — things become strange indeed, not quiescent, as one might expect at the eye of a storm, but more violent. Strong magnetic fields squirt jets of gas out of the galaxy, and supernova explosions trigger massive disruptions.

At the core of the Galaxy, stars flash into existence, blaze with a quick intensity, and explode. Stars collide, or tear at each other with gravitational claws. The density of stars is a million times greater than in the arms of the Galaxy. If there are inhabitants of planets here — which seems unlikely given the terrible violence of the neighborhood — their night sky shines with a fierce brilliance.

At the very axis of the Milky Way probably lies a black hole with the mass of a million suns — the monster in the pool, the dark heart of the Galaxy. Episodically, fits of gas stream into the black hole, gushing energy outward before disappearing forever into oblivion.

Every dark pool should have its monster. Every dark pool should be haloed with light. The Milky Way is quiescence and violence, radiance and darkness, life and death — a whirlpool of creation and destruction.

Astronomers have sketched the thousand billion stars. The Milky Way is no longer the threshold of infinity; we have plumbed its depths, searched its hidden crannies, and glimpsed worlds more wonderful and bizarre than anything we have known in our Solar System. It is home.

Go to sleep now, children. As the first true citizens of the Milky Way you’ll need your rest. Your century is about to begin.

This bedtime story draws upon “The Centre of the Milky Way” by Leo Blitz, James Binney, K. Y. Lo, John Bally and Paul T. P. Ho in the February 4, 1993 issue of Nature. -Ed.