Originally published 13 October 1997

A lifelong sky watcher, I recently had the opportunity to watch the sky on the day of my birth, September 17, 1936, at the place of my birth, Chattanooga, Tennessee.

As dawn gathered in the east, Mars was shining red in Leo, not far from the place of the rising sun and close to the bright star Regulus. Saturn was sinking in the west.

The sun rose nearly dead east, sliding up into a deep blue sky to begin its run above the equator.

At sunset, a spectacular conjunction of Venus, Mercury, and a day-old crescent moon, was briefly visible in the west. Higher in the evening sky, Jupiter in Scorpio dove to follow the sun.

I watched the day and night of my birth slip by on the screen of my computer. For my birthday, my wife gave me sky-simulation software called Starry Night Deluxe that displays the sky anytime, anywhere. I’ve used sky-simulator programs before, but this one is the best — and certainly the most fun.

The sky views are realistic. The sky brightens and darkens as the sun rises and sets. Stars and planets come out one by one in the evening sky. Trees adorn the horizon (they even cast shadows). If you adjust the program so that the view is straight down, you can see your feet.

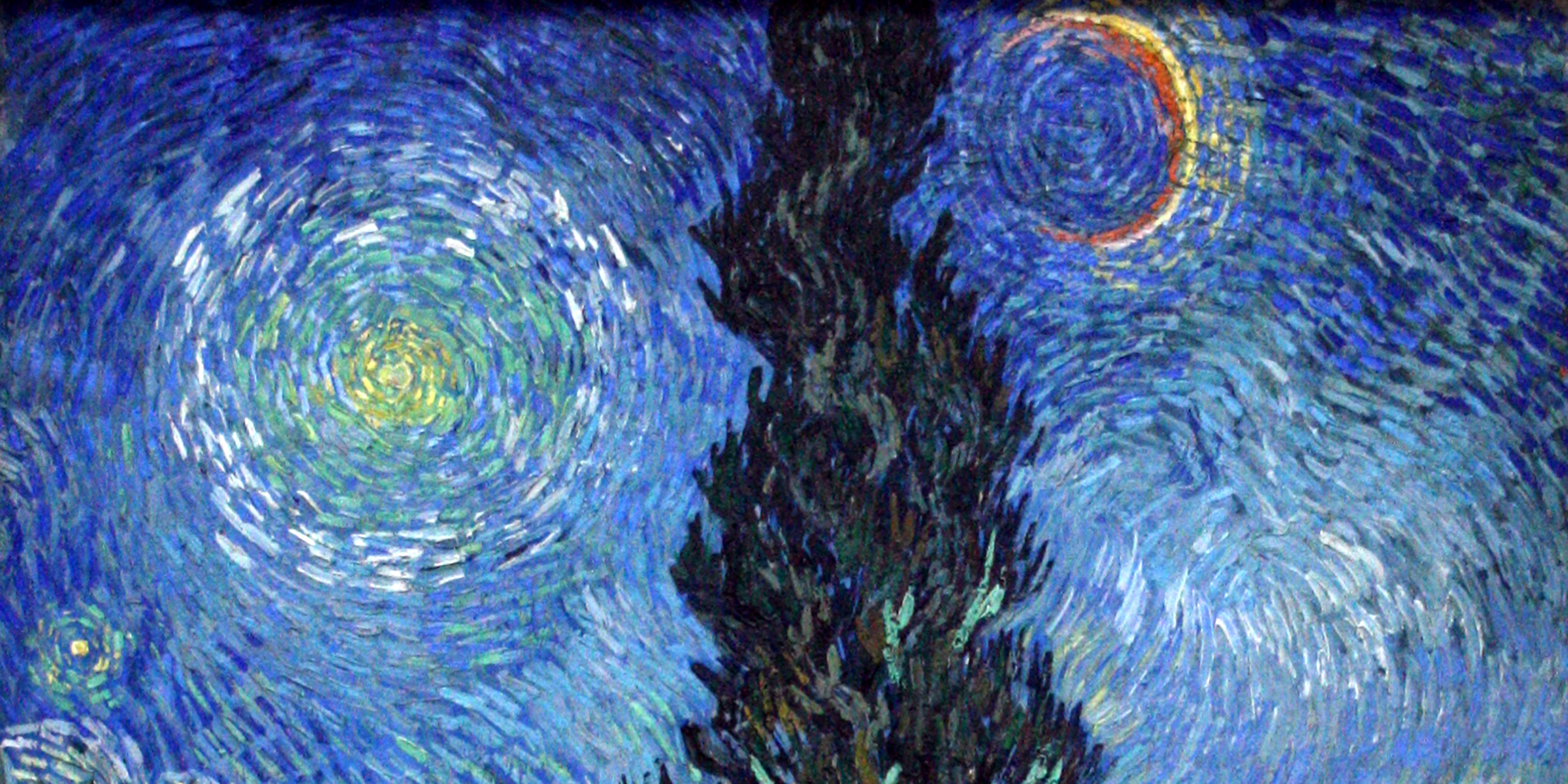

The name of the software, Starry Night Deluxe, evokes Van Gogh’s famous painting The Starry Night, with its blazing stars and vortices of color. In fact, a reproduction of Van Gogh’s painting is used on the start-up screen of the program.

The sky in The Starry Night is a product of Van Gogh’s fervid star-struck imagination. But another of the artist’s paintings, Road with Cypress and Star, is probably based on an actual observation. Some years ago, physicists Donald Olson and Russell Doescher suggested in Sky & Telescope magazine that Van Gogh may have witnessed a conjunction of celestial objects like those in the painting, at about the time the painting was made.

With the software, I went to Saint-Rémy in the south of France on the evening of April 19, 1890. I stood with Van Gogh at the window of the asylum where he had confined himself because of his disturbed state of mind. I set the program in motion, and watched the sun sink in the west, imagining with my mind’s eye a foreground road with cypresses.

As the sun dipped below the horizon, a whisper thin crescent moon appeared in the fading light, only a day-and-a-half past new, a striking sight under any circumstances, but made even more dramatic by the close proximity of blazing Venus and bright Mercury.

This beautiful conjunction of celestial objects would certainly have been noted by anyone with a passing interest in the sky, and we know that Van Gogh was keenly interested in astronomy. As the moon and planets set, and the sky darkened on the screen of my computer, it was easy to imagine the artist’s excitement, his desire to fix onto canvas the beauty he had just seen, transformed and heightened by his imagination.

The Starry Night Deluxe sky-simulation software is fun, but how good is its science? How accurately does the program reproduce skies of long ago?

In January 1997, Sky & Telescope magazine published a letter from someone who had used sky-simulation programs to reproduce the first recorded celestial observation made by Nicholas Copernicus, on the evening of March 9, 1497, when Copernicus was a student in Bologna, Italy. This was nearly half a century before the great astronomer published the book that set the Earth spinning on its axis and moving about the sun.

Copernicus tells us that he watched the moon move in front of the star Aldebaran. However, according to Sky & Telescope’s correspondent, three simulation programs showed the moon passing by Aldebaran without covering it.

Was Copernicus mistaken? The problem was that the computer programs did not take into account the proper motion of the star, a tiny drift through space that is generally too small to be noticeable, but which can accumulate over hundreds of years.

Starry Night Deluxe software does include the proper motion in its calculations. I configured the program for Bologna, Italy, on March 9, 1497. Sure enough, the moon passed in front of the star, which winked out behind the dark limb of a crescent moon. It was almost like being there, with the young Copernicus, making his historic observation.

Copernicus was led to his revolutionary hypotheses about the motion of the Earth by his desire to find a way to more exactly compute past and future celestial events. In particular, he was interested in finding a better way to predict the dates of Easter, a feast whose celebration is fixed by celestial happenings. Copernicus was following a quest begun by Greek astronomers of antiquity, to find a computational theory that reproduces the observed motions of sun, moon, and planets.

Hipparchus, Eudoxos, Ptolemy, Copernicus, Kepler, and Newton would have loved to have seen where their efforts would take us — a celestial simulator of exquisite accuracy available for every home computer.

Coincidentally, next Sunday morning in the hour before dawn, the moon will pass over bright Aldebaran, 500 years after Copernicus watched a similar event. The blinking out of the star will be visible in the western sky, although the fat gibbous moon will be so bright that you will need a small telescope to watch the actual moment of disappearance. I know. I have already watched it happen on the screen of my computer.