Originally published 17 June 2003

What was the greatest scientific idea of all time?

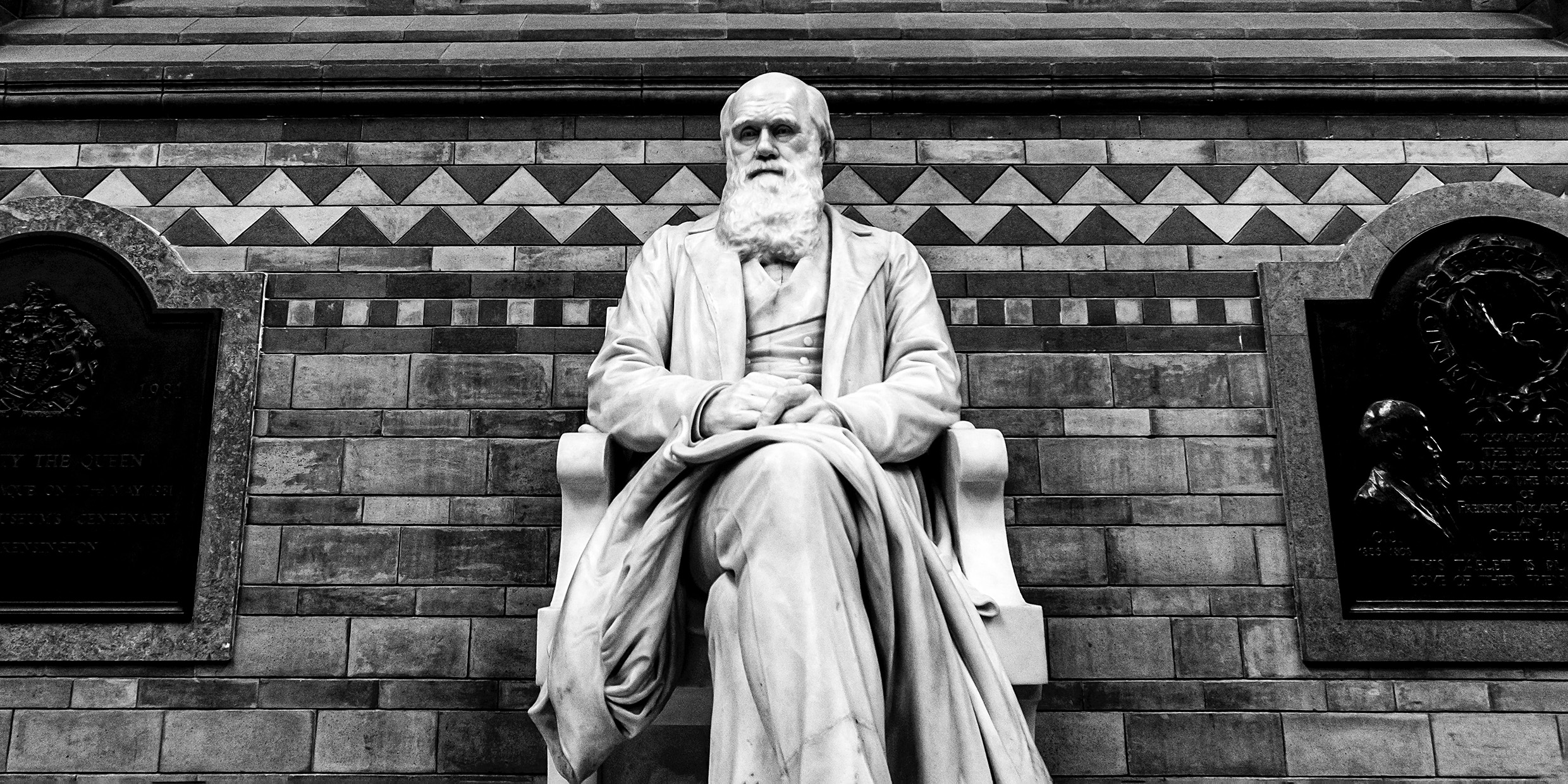

The answer, I think, is clear: Evolution by natural selection, conceived more or less simultaneously by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace in the mid-19th century. It was their genius to imagine a way diverse organisms could arise from simple ancestors by purely natural process.

As Darwin and Wallace clearly understood, if three conditions apply — replication, variation (mutation), and competition for limited resources — evolution is not just a possibility, it is a logical necessity.

What was not understood in their time was the genetic basis for replication and mutation, so their premises were based on a certain amount of speculation. Today, all three conditions for evolution are well understood and amply confirmed.

Nevertheless, a conceptual difficulty remains, as it did for Darwin. How can certain complex structures with multiple interacting components, such as the human eye, arise from any conceivable combination of random, single-function mutations of an organism’s genes?

Opponents of Darwinian evolution call this the problem of “irreducible complexity.” The chance that a combination of random mutations might produce something as complex as the human eye is vanishingly small, they say. Complexity requires a designer. Evolution may occur, but it will go nowhere unless an intelligent outside agency intervenes at key points in the process.

The argument is not new. As long ago as 1800, the English theologian William Paley used the example of a man walking on a heath who finds a pocket watch among the pebbles. The man might consider the pebbles to be a product of natural causes, Paley stated, but he would never believe the watch to be other than the product of intelligent design.

Until recently, there was no way for evolutionists to persuasively answer this objection. It was clear that organisms might find ways to combine simpler, independently-evolved functions to perform complex operations, but the fossil record is too spotty to demonstrate the supposed intermediate steps toward complexity.

Enter the high-speed digital computer.

It is now possible to create artificial organisms — self-replicating computer programs — that meet the three requirements for evolution: replication, random mutation, and competition. These artificial organisms go through thousands of generations in minutes or hours of computer time, and every step of the process can be observed. They evolve surprisingly complex structures.

In the May 8 [2003] issue of Nature, an interdisciplinary group of researchers at Michigan State University and the California Institute of Technology describe one such experiment.

They created a simple, self-replicating, computer virus-like ancestral “organism,” subject to random mutations of its program. The organism’s descendants compete in cyberspace for the “energy” necessary to execute instructions. They are rewarded according to their evolved ability to perform logical operations that were not part of the original program.

As in nature, some mutations were beneficial, some were neutral, and many were deleterious. Nevertheless, remarkable logical complexity emerged. An ancestor that could only make copies evolved descendants able to perform multiple logic functions requiring the coordinated execution of many program instructions.

As these computer experiments continue — and this is not the first — the insights of Darwin and Wallace become ever more compelling.

For example, Stanford University’s John Kosa and colleagues have programmed a powerful computer to use replication, mutation, and competition to digitally evolve useful electronic circuits, including many devices for which patents had been previously granted to human inventors. They anticipate that a patent might soon be granted for an invention that is entirely their computer’s own.

Opponents of Darwinian evolution might object that these evolutionary computer programs are themselves products of human intelligent design. Yes, but so what? They still demonstrate that complex organisms can arise from simple ancestors by purely natural process.

Replication, variation, and competition can indeed produce unanticipated complexity. In fact, one rather fears the time when malicious hackers let loose into cyberspace destructive virus-like artificial organisms that employ Darwinian principles to evolve ever more resourceful ways of eluding our efforts to control them.