Originally published 10 November 1997

From southern Australia comes news of the sex life of the giant squid.

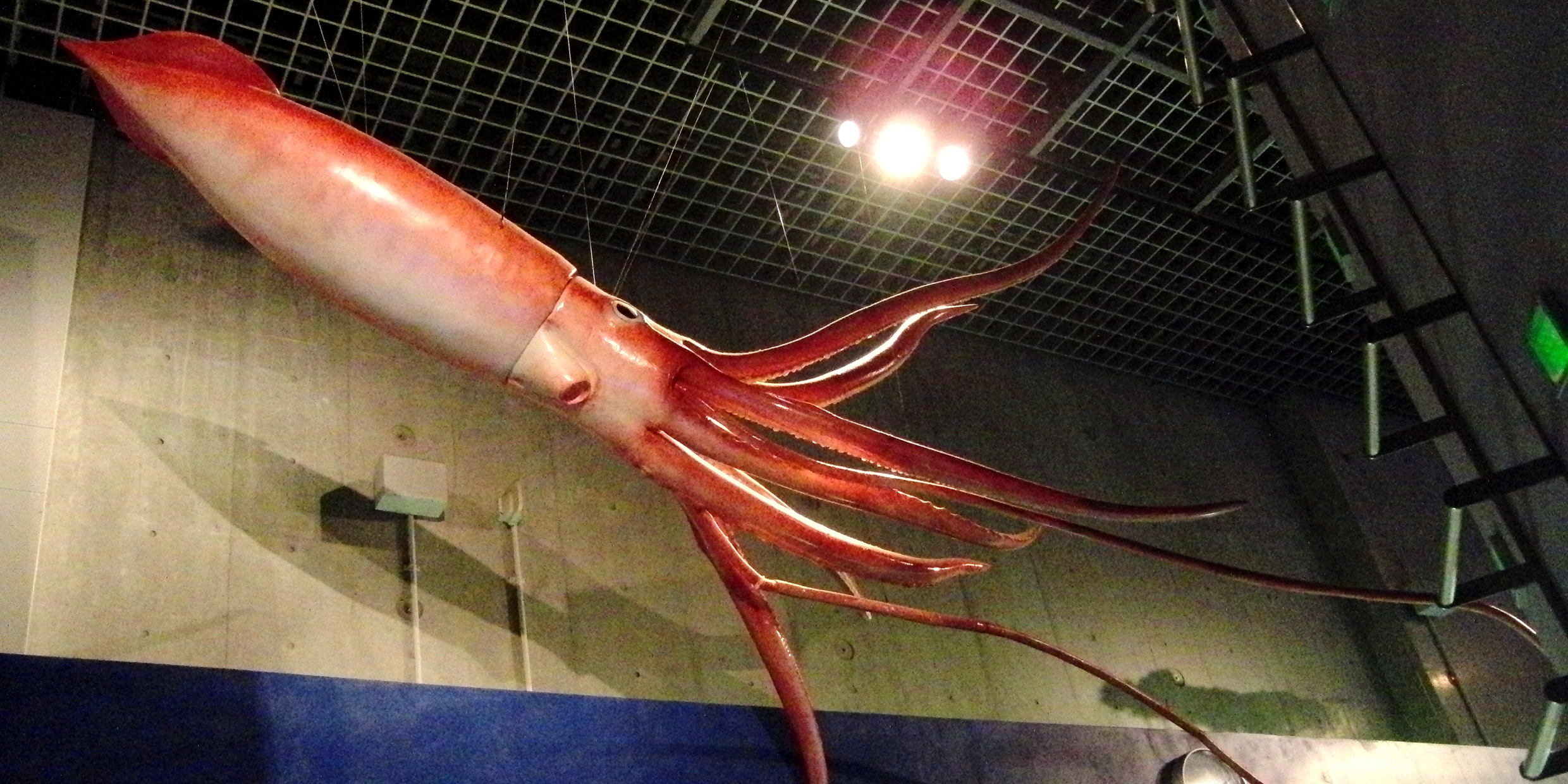

This almost mythical sea creature is one of Hollywood’s longtime favorite monsters. It grows to more than 60 feet in length, with eight powerful arms and two long tentacles covered with toothed suckers. Each of the squid’s two eyes is the size of a human head. Add a parrotlike beak and you have one scary animal.

No wonder scientists know so little about the giant squid, and particularly about its sex life. What researcher wants to get close to one of these terrifying beasts, especially during its most intimate moments?

In a recent issue of the journal Nature, two Australian zoologists report the first ever capture of a mated female, and from their examination comes a mind-boggling story of copulation in the deep.

Apparently, the male giant squid embraces the female with its many arms, then uses its muscular 3‑foot-long penis to inject tubes of sperm directly into the female’s skin, maybe under powerful hydraulic pressure. The female uses these sperm packets at her leisure to fertilize her spawn.

In inky-dark ocean depths it is perhaps only infrequently that male and female giant squids find each other. This may explain why the female gathers what sperm she can by violent injection, a kind of fertilize-it-yourself “nicotine patch.” Since no one has ever observed a female giant squid release eggs, it is not known how she gains access to the stored sperm. Perhaps she rips open her own skin with her suckers or beak.

Lately, Hollywood seems obsessed with graphic slam-bam sex. The mating of giant squids should be natural movie material. The dark. The thrashing arms. The ensnaring, sucking tentacles. The helmeted heads, the unblinking dinner-plate eyes, the beaks. And the male shooting sperm packets into his mate’s arms.

If at this point your sympathy is with the female giant squid, which must bear the indignity of hydraulically-injected sperm and then mutilate herself to get at it, listen to the sad story of the male Photinus firefly.

Female fireflies of the genus Photuris have learned to flash the love call of another genus, Photinus. A Photinus male sees the blinking come-hither signal and, love-besotted, comes calling to mate. The Photuris female, which presumably has no trouble finding a mate of her own kind, gobbles up her unsuitable suitor. Her ruse is designed to attract a meal, not a lover.

And more. Entomologists at Cornell University have now discovered that the female Photuris gains something besides nourishment. A Photinus firefly’s body contains a venomous chemical that makes it unpalatable to spiders and birds. When Photuris eats her unwary suitor, she ingests this chemical, thereby making of herself an unappetizing meal. Seldom in the animal world does seduction lead to so ignominious a fate on behalf of the seductee.

This firefly scenario also has the makings of a macabre Hollywood plot, perhaps with Linda Fiorentino playing the human equivalent of the female Photuris.

With these recently-published observations of the love lives of squids and fireflies, the encyclopedia of bizarre animal sex becomes yet more voluminous.

Sex is such an unlikely — and apparently unnecessary — way to accomplish reproduction that biologists wonder why it exists at all. We have seen a spate of new books lately on the origins and evolution of sex, with an emphasis on the many ways animals have devised to insure the propagation of their genes.

Next month, University of Massachusetts biologist Lynn Margulis, with science writer Dorion Sagan, will publish a “lavishly illustrated” book called What Is Sex? Margulis’s speciality has been bacteria, and even these tiniest of nature’s creatures apparently enjoy pleasures of the flesh — such as they are for blobs of protoplasm without brains. Margulis and Sagan will undoubtedly begin with bacteria and work their way up to such paragons of dalliance as fireflies and giant squid.

The well-known biologist Jared Diamond recently hit the market with a book called Why Is Sex Fun? The Evolution of Human Sexuality, which also looks for the origins of human sexual physiology and behavior in the history of our genes. Let’s hope that all of this reductionist Darwinizing doesn’t take the fun out of it.

My own longtime favorite book about the ecology and evolution of sex is biologist Adrian Forsyth’s A Natural History of Sex, a fun compendium of sexual practice among the beasties. Here one can read about the incredible array of anatomical devices and quirky behaviors that animals have evolved to ensure the survival of their species, including the counterproductive love call of the male three-wattled bellbird of Central America, so enthusiastically loud that its great bell-like “BONG” can knock a prospective mate right off her perch.

Of course, nowhere in nature does sexual practice become more bizarre than among our own kind. All it takes is an afternoon watching TV talk shows to realize that nothing among the birds and bees can top Homo sapiens for quirky sexual behavior.