Originally published 15 December 1986

How could I resist a book with a chapter called “Three Billion Years of Sex?”

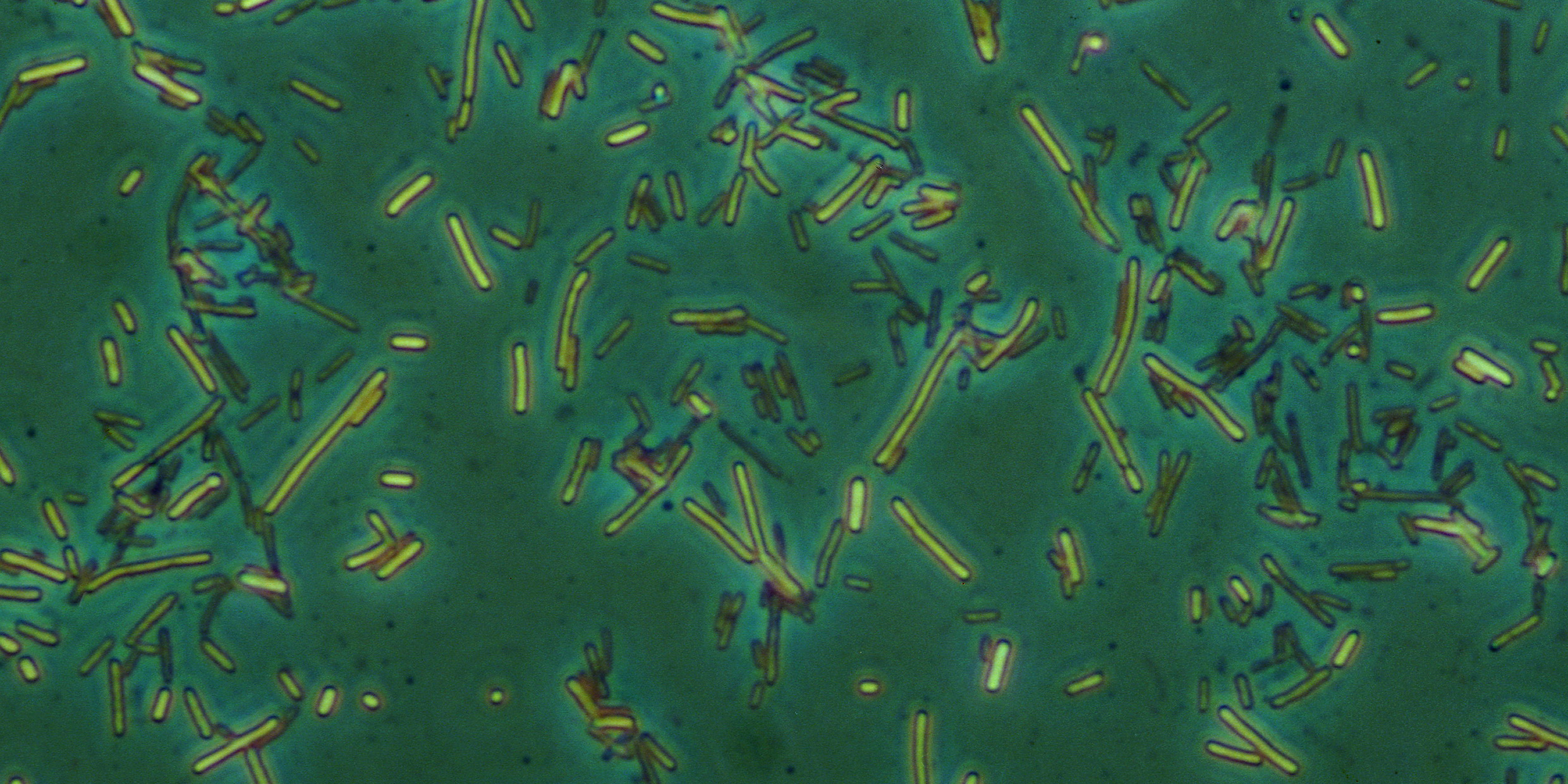

But wait. Before you rush out to buy it, you should know that this book is about microbial sex, those zillions of tiny couplings between bacteria that kept life going on Earth for 3 billion years before such things as clams and starfish arrived on the scene to liven things up.

The book is Origins of Sex by Boston University biologist Lynn Margulis and writer Dorion Sagan, published earlier this year by Yale University Press. It’s a marvelous concoction, full of good science, good prose, and provocative speculation.

Margulis is an evolutionary biologist who can be relied upon for unconventional but insightful views about how it all happened. She is a great fan of bacteria. Sometimes you get the feeling that Margulis believes creatures like you and I are just huge crowds of bacteria that managed to get themselves organized into walking, talking macroscopic clumps. In Margulis’ view, everything really interesting was invented by microbes: individuality, cooperation, metabolism, motility, photosynthesis, respiration, and now, in this book, the best thing of all — sex.

Reproduction and sex

Margulis and Sagan make a clear distinction between sex and reproduction. Reproduction appeared with the very first organisms. One thing shared by all living cells is a continuous replication of DNA, the molecules that contain the genetic information. Perhaps, Margulis and Sagan believe, organisms reproduce precisely because they never stop making DNA and other large molecules (RNA and proteins). When a bacterium gets too big it tends to divide. Each offspring of the split takes along a complete copy of the original genes. Two individuals have replaced one. That’s reproduction, and it appears to be a biological imperative.

Sex, on the other hand, is gravy. Sex is icing on the cake. Life, reproduction, and evolution could have happened without it. We could all divide like amoebas, spread spores like fungi, or bud like tree cuttings. It is only because of accidents of evolution that sex appeared at all.

Margulis and Sagan define sex as any process that brings rogether in a single individual genes from at least two sources. We know what that means for human beings, but the authors of this book have something much broader in mind. When a virus invades a cell and inserts its genes into the DNA of its host, that’s a sex act. When several hundred slime mold cells come together to produce one Acrasia slug, that’s sex. When two paramecia conjugate, exchanging DNA through their cell walls, that’s sex. One wonders at what level in the ladder of life this promiscuous mixing started being fun.

And why did this business of gene swapping begin at all? Margulis and Sagan take the unconventional view that sex evolved as a DNA repair mechanism, in response to threats from ultraviolet light.

Started with photosynthesis

The story goes something like this. Early in Earth’s history certain bacteria evolved the ability to make sugar from sunlight and water, a process called photosynthesis. At that time there was no free oxygen in the atmosphere and, because ozone is a form of oxygen, no ozone layer to screen out ultraviolet light from the sun. Bacteria needed sunlight for photosynthesis, but ultraviolet rays had the tendency to damage the delicate genetic material of the cells. And so evolved a battery of mechanisms for ultraviolet protection, including molecules called enzymes that repaired damage to DNA integrity. These enzymes became the basis for sexuality. They were the chemical equipment that enabled cells to cut, splice, share, and repair DNA.

Oxygen is a by-product of photosynthesis. After millions of years of bacteria making food from sunlight, the level of oxygen in the atmosphere increased, and finally ozone blocked the deadly ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Still, organisms retained the DNA cut-and-splice techniques for various reasons, not least of which was their continuing usefulness for preserving the integrity of the genes in the face of other threats and poisons.

Margulis and Sagan trace the evolution of sex across 3 billion years. The story they tell is closely tied to Margulis’ controversial theory of cell evolution by symbiosis. According to Margulis, the many-compartmented “modern” cell — with a nucleus for DNA, chloroplasts for photosynthesis, mitochondria for respiration, and whiplike appendages for mobility — evolved by a coming-together for mutual benefit of smaller, specialized organisms. Through all of this constructive cooperation, new ways of exchanging and sharing DNA were incorporated into the stream of life. The apparatus of sex was stretched and polished.

Margulis has always insisted that we have much to learn about ourselves by studying microbes. In this book, she extends that idea to sexuality. The views expressed by Margulis and Sagan will annoy some readers and drive some conventional biologists into frenzies of disdain. I’m no biologist, but to me the story told in Origins of Sex has the ring of truth.

My god!!!!! (as if one exists)

Thank you. THANK YOU. THANK YOU.

I just rediscovered the blog, after so many years of it being dormant. THANK YOU.

15 years ago, in a long long letter I sent to Chet in Ventry, Ireland, after meeting him at Quinn’s pub in Ventry while on a family vacation, I begged him to turn his Globe articles into a book. This is almost just as good, but you can’t really hug your pc monitor the way you can embrace a book! Words are completely inadequate for the respect, awe, and feelings I have for Prof. Raymo. Enough said. Thank you, whoever you are!!!!!!

You’re welcome! Enjoy the archive!