Originally published 5 December 1994

News Note: Bill Gates, chairman and CEO of Microsoft, the world’s largest supplier of computer software, made the winning $30.8 million bid for a Leonardo da Vinci manuscript called the Codex Hammer. Gates has been described by Forbes magazine as the richest man in America.

The Codex Hammer is not the first Leonardo manuscript to come to America. Another secretly crossed the Atlantic 20 years ago. Let me explain:

About 1482, young Leonardo da Vinci sent Lodovico Sforza, duke of Milan, a letter in which he offered his services as an engineer.

“Most illustrious Lord,” he wrote. “I am emboldened to put myself in communication with Your Excellency, in order to acquaint you with my secrets, thereafter offering myself at your pleasure effectually to demonstrate at any convenient time all those matters which are in part briefly recorded below.”

His list of proposed accomplishments begins with instruments of war: “I have plans for bridges, very light and strong and suitable for carrying very easily, with which to pursue the enemy…I have plans for destroying every fortress or other stronghold unless it has been founded upon rock…I have also plans for making cannon, very convenient and easy of transport…I can supply catapults, mangonels, trebuchets and other machines of wonderful efficacy.”

Leonardo goes on to describe inventions in the fields of naval warfare, architecture, sculpture, and painting.

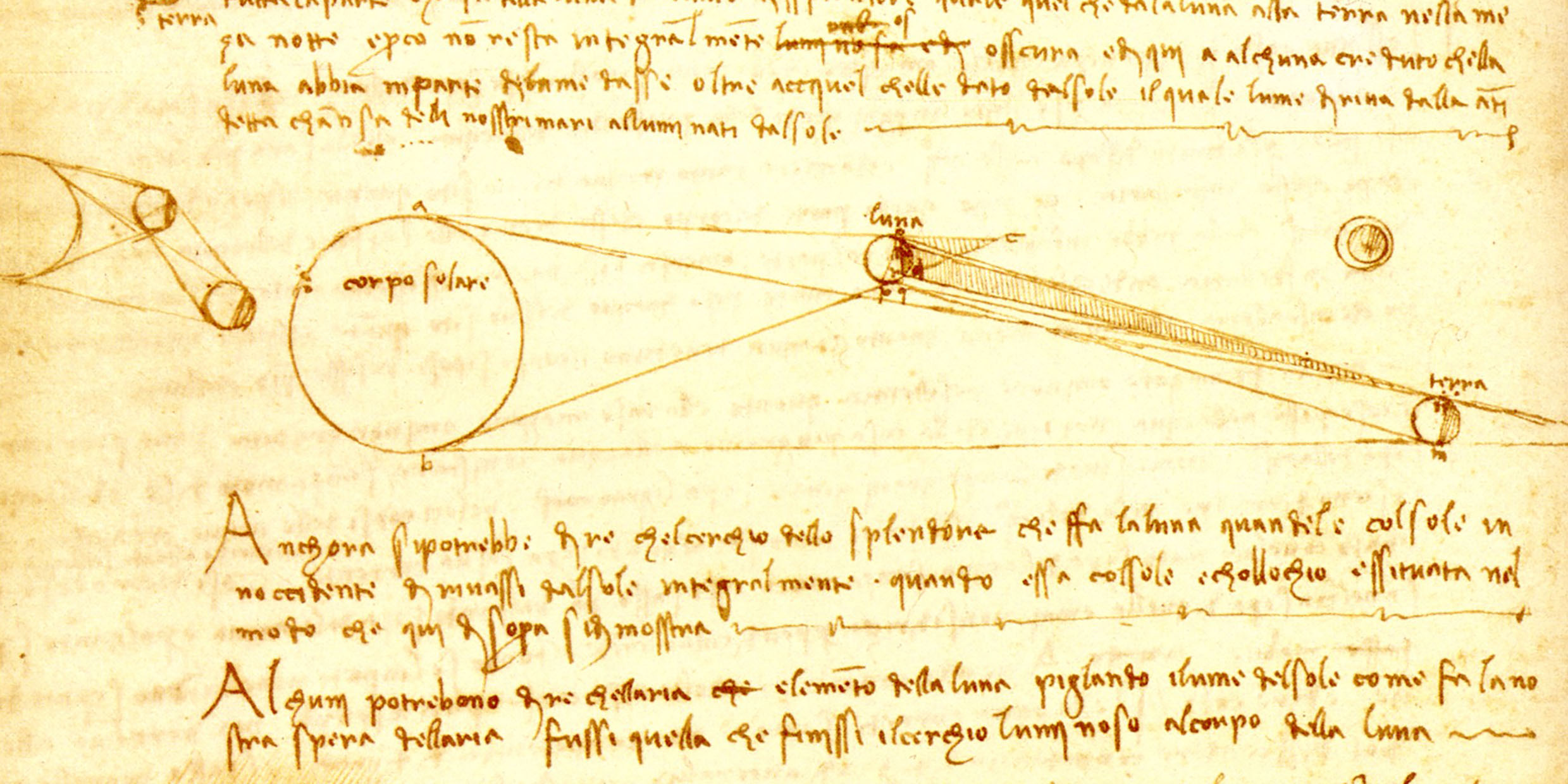

Scholars have often remarked upon the wide range of Leonardo’s technical proficiency, and upon his uncanny ability to anticipate many modern technologies. In his notebooks can be found sketches for flying machines, helicopters, parachutes, military tanks, spring-driven cars, flying spindles for weaving cloth, powered lathes and saws, boring and stamping machines, and prefabricated houses. The products of his fertile imagination are endless.

At the end of his letter to Lodovico Sforza, Leonardo challenges those who might doubt his talents: “And if any of the aforementioned things should seem impossible or impractical to anyone, I offer myself as ready to make trial of them in whatever place shall please Your Excellency.”

But was this last remark really the end of the letter? Certain scholars (I forget their names right now) have argued for the existence of a “missing page” to the Lodovico letter, containing a further enumeration of Leonardo’s inventions.

Without revealing my sources, I am able to announce that the “missing page” does in fact exist, and that it was discovered in a Paris flea market 20 years ago by a young American who desperately wants to keep its contents secret.

A photocopy of this important document has come into my hands. In sharing it with my readers, I have rendered some terms both in the original Italian and in English.

Leonardo continues: “It will behoove Your Excellency to note that all of the aforementioned instruments and devices can be categorized as mercanzia dura (hardware). However, I am also able to provide mercanzia soffice (software) of diverse and sundry sorts. I foresee the day when the control of informazione will be more important to Your Excellency’s wealth and power than all machines, fortresses, and palaces.”

“Presente! (Don’t miss the boat!),” writes Leonardo.

He professes to know how to construct macchini personale per cacolare, which, as best as I can understand his meaning, would be similar to modern computers. However, he informs Lodovico that these machines can best be made by others, while he will confine himself to the sviluppo (development) of the corresponding mercanzia soffice.

“There are molta moneta (big bucks) to be made in prodotti d’informazione (information products),” he adds confidently.

One long passage in the letter refers to something Leonardo has invented called “Finestre” (windows). It is difficult to make out exactly what he has in mind, but Finestre seems somehow related to making his machines easier to use. “As easy as watching a pomo (apple) fall from a tree,” he writes.

Another invention, which Leonardo refers to as la rete (the net), is presumably a way of connecting many macchini personale per cacolare into a single larger entity. While the details of this idea are not clear, he tells Lodovico that success in this endeavor will mean molta, molta, molta moneta.

Certainly the most extraordinary idea to be found anywhere in Leonardo’s writings is his proposal to put hundreds of piccole lune (little moons) into orbit around the Earth, which would be used to reflect la rete from place to place. He assures Lodovico that if this is accomplished, Milan will become the world’s luogo caldo per informazione (data hot spot) and the duke will achieve a lucrative presa strangolare (monopoly) in the business of communications.

Leonardo concludes: “All of these things can be readily accomplished at the request of Your Excellency, to whom I commend myself with all possible humility.”

My sources tell me that the “missing page” of Leonardo’s letter to Lodovico is currently locked in a vault somewhere in the American Northwest. I leave it to my readers to decide who stands to gain by the continued suppression of this important document.