Originally published 17 September 1990

The father of evolution was worried sick.

That’s the literal conclusion of a new biography of Charles Darwin by British psychiatrist John Bowlby.

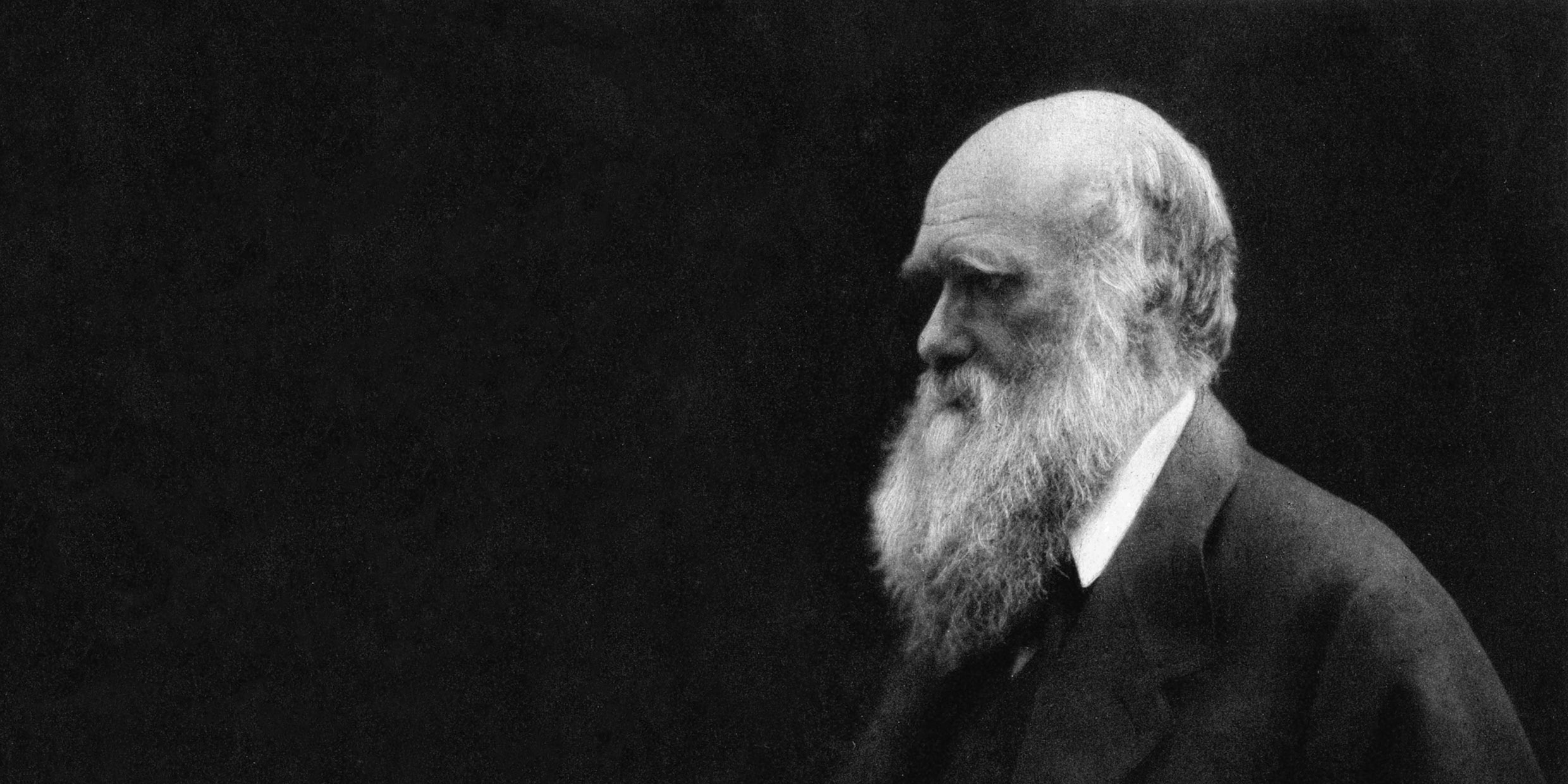

The portraits of Darwin that accompany Bowlby’s book tell the story of the great man’s state pf mind almost better than the text. The earliest portrait shows Charles at age 7. Even in the child’s face it is possible to detect a certain unchildlike seriousness, a barely-perceptible furrowing of the brow. We are given other portraits at ages 33, 40, 44, 45, 60, 66, and 72.

The expressions become progressively more somber, the brow more deeply furrowed, the kindly eyes filling to brimming with accumulating sadness. Even allowing for the typical sternness of Victorian portraiture, we are impressed by the visage of a soul in torment.

Few scientists have contributed more to our understanding of the world than Charles Darwin, and few scientists have worked under the burden of a more severe infirmity. For most of his life, Darwin suffered debilitating symptoms: gastric disorders, vomiting, palpitations and pain around the heart, ringing in the ears, black dots before the eyes, and skin rashes.

An array of maladies

These physical symptoms were accompanied by paralyzing psychiatric problems: panic attacks, depression, excessive nervousness, fear of death. On numerous occasions Darwin was incapacitated for months on end. Never from the age of 30 did he feel completely well.

Bowlby’s chapter titles are phrases drawn from Darwin’s letters. They read like a litany of woe: “a voyage grievously too long,” “a bitter mortification,” “grief never wholly obliterated,” “a fearful disappointment,” “an odious spectre.” One wonders how in the midst of such unremitting gloom Charles Darwin managed to accomplish anything at all.

Yet his output was enormous. He authored 13 major scientific works, including the epoch-making Origin of Species, arguably the most influential scientific book of all time. His letters to friends, relations, and scientific colleagues comprised an inexhaustible flood.

Darwin’s colleague, the botanist Joseph Hooker, wrote of him: “His powers of observation, memory and judgement seem prodigious, his industry indefatigable and his sagacity in planning experiments, fertility of resources and care in conducting them are unrivaled, and all this with health so detestable that his life is a curse to him and more than half his days and weeks are spent in inaction – in forced idleness of mind and body.”

Exactly what was Darwin’s affliction? According to some modern writers, Darwin suffered from Chagas disease, a parasitical infection common in South America caused by the bite of an infected bug, and presumably acquired by Darwin during his early voyage to the southern continent aboard HMS Beagle.

More often, modern doctors reject an organic cause for Darwin’s illnesses in favor of a psychosomatic diagnosis. After reviewing all the evidence, John Bowlby argues persuasively that Darwin’s symptoms were due to hyperventilation (overbreathing that starves the blood of carbon dioxide) caused by chronic anxiety. Darwin’s skin eruptions, too, were presumably caused by psychological stress.

In spite of his many visits to physicians and surgeons, Darwin seems to have guessed that his problems were psychosomatic. In a letter to his sister Caroline he writes “I find the noddle and the stomach are antagonistic powers… What thought has to do with digesting roast beef, I cannot say, but they are brother faculties.”

His scientific friends and colleagues also suspected that Darwin’s symptoms were not organic, and sometimes hinted to Darwin that his eagerly pursued water cures and special diets were not the answer. Of course, it doesn’t help a person who suffers from pyschosomatic symptoms to be told his illness is all in his mind.

In an earlier book on Darwin’s illnesses, Ralph Colp maintained that the naturalist’s long years of poor health were caused by anxiety engendered by his ideas of evolution; Darwin knew that his radical theories, especially about human origins, were sure to cause controversy. John Bowlby agrees but sets Darwin’s anxiety into a broader context of childhood influences.

More than a diagnosis

Two things in particular attract Bowlby’s attention: the death of Darwin’s mother when he was eight years old (an event which was shrouded in an unnatural family silence), and Darwin’s “deep desire to earn the approval of his father and other father-figures and, at all costs, to avoid arousing their criticism.”

Bowlby’s superb biography is more than a diagnosis. What begins as a study of the psychological sources of Darwin’s symptoms expands into a full-scale study of the great naturalist’s state of mind, and of the circle of family and friends that sustained and nurtured him.

We are given the picture of a devoted son and father, an affectionate husband, and loyal friend, much loved and admired by all who knew him, who was also a worry-wart and hand-wringer, wounded by the loss of a mother’s love, brilliantly creative and desirous of fame but terrified that he would be found wanting by father, by friends, by the scientific community, and by history.

Charles Darwin was made grievously sick by the expectation that his views on evolution by natural selection (survival of the fittest) would be greeted with contempt. If his ideas have survived the test of history it is not because the man himself was physically fit.