Originally published 25 February 1985

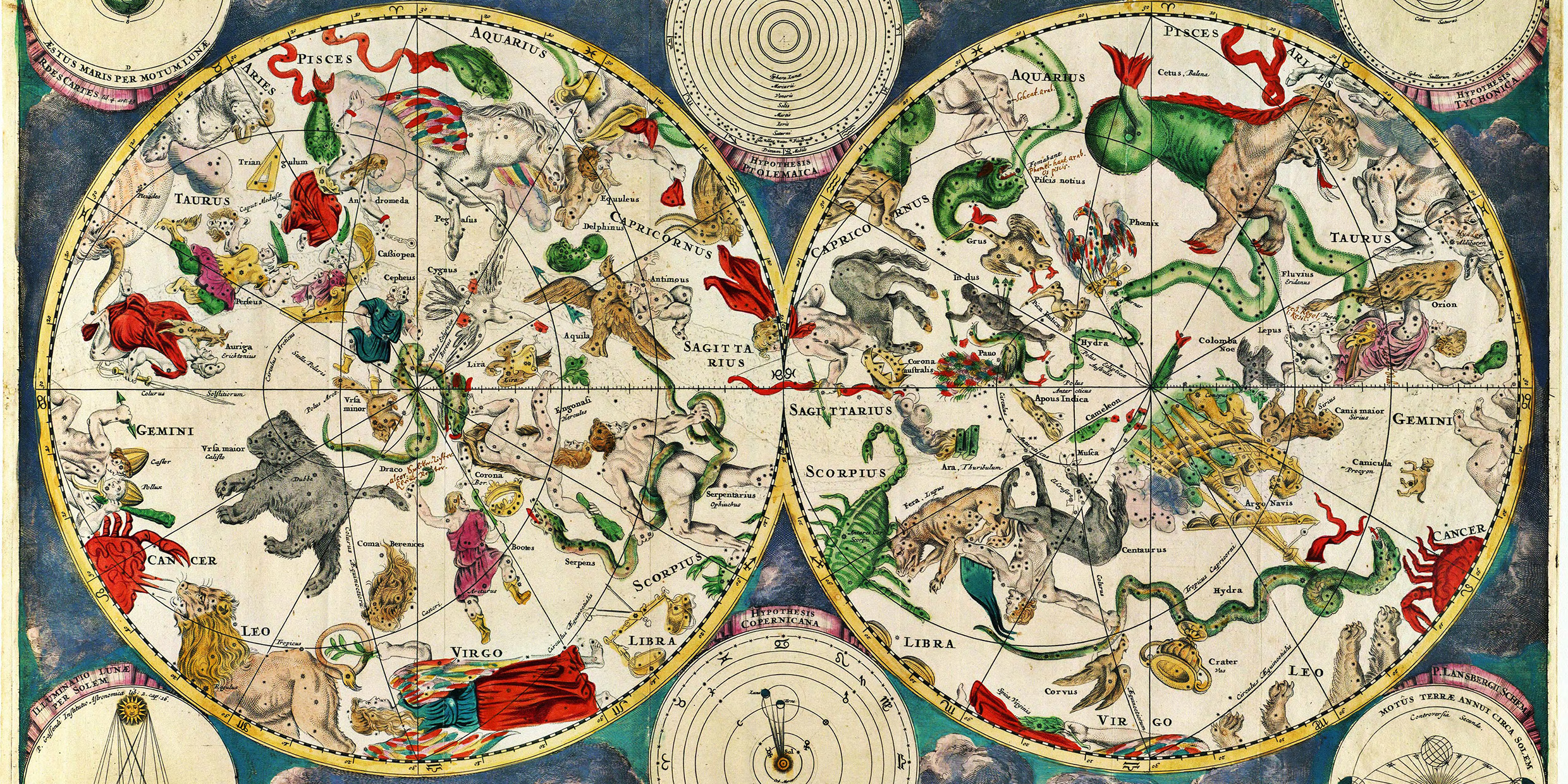

Who invented the constellations? Who first imagined the confrontation of Taurus and Orion in the winter sky? Who placed the figures of the Great Bear and the Little Bear near the northern pole? Who sent Cygnus the Swan winging along the stream of the Milky Way?

Most of the constellations that are familiar to northern observers are very ancient. The mystery of their origin has long intrigued archeologists and prehistorians. In a recent issue of Vistas in Astronomy, Archie Roy of the University of Glasgow reconstructs the mystery, and offers a new theory for how, when, and where the constellations came into being.

A debt to the Greeks

This much is certain: The familiar constellation and their attendant myths — as we know them — are essentially Greek. Plato’s student Eudoxus described our system of constellations sometime between 400 and 350 B.C. He left to his successors a star globe know as the Sphere of Eudoxus. The works of Eudoxus have been lost, including the sphere, but we know of his ideas through an account of Aratus, who wrote about 220 B.C. In Aratus we find descriptions of Orion, Sagittarius, Scorpio, Gemini, and dozens of other constellations that still grace our star maps, along with their positions in the sky.

Did Eudoxus, then, invent our system of constellations? Or did he inherit the system from a still more ancient source — the Babylonians, perhaps, or the Phoenicians, or the Egyptians? The answer these questions, we must become astronomical detectives.

The Earth is surrounded on every side by stars. Ancient peoples imagined that the stars resided on an all-enclosing celestial sphere, a sky sphere that was concentric with the Earth.

Not all of the stars on the “sky sphere” are visible from a particular place on Earth. For example, as the Earth turns under the sky (or, as the ancients would have said, as the sky turns over the Earth), an observer in Boston has a chance to see about two-thirds of all the stars in the sky. Stars close to the sky’s southern pole never rise above the horizon of Boston. To see those stars a Bostonian would need to travel south.

The constellations described by Aratus do not include a region of stars near the sky’s southern pole, just as we might expect if the constellations were invented in the northern hemisphere. The size of the blank region on the Sphere of Eudoxus (as described by Aratus) corresponds to that part of the sky that could not be seen by an observer who lived about 36 degrees north of the equator. That is close to the latitude of Greece. The evidence points to Eudoxus.

But wait! The center of the region of uncharted stars does not correspond to the southern pole at the time of Eudoxus. Aratus describes stars that Eudoxus could not have seen, and leaves out stars that Eudoxus could have seen if only he had looked.

The reason is not hard to find. As the Earth spins, its axis wobbles like a top. Because of the wobble, the northern and southern poles of the sky continuously change, although very slowly. The stars that are not included in the constellations of Eudoxus are centered on the place in the sky that was the southern pole in 2000 B.C. Eudoxus must have inherited the constellations: he did not invent them.

According to Roy, the originators of our system of constellations must have lived around 2000 B.C. at a latitude of about 36 degrees north of the equator.

We can rule out the Egyptians because they lived too far south. We can rule out the Phoenicians because they prospered too late. What about the Babylonians? They were passionate observers of the sky. The latitude is right, the time is right. The Babylonians have long been suspected of being the principal source of Greek astronomy.

But let’s ask why the constellations were invented. Roy argues they were intended primarily as aids for navigation at sea. He bases this assertion on the fact that the patterns of constellations were orientated with respect to the poles and equator of the sky, rather than with the stars (the Zodiac) that mark the change of the seasons. This suggests, says Roy, that the constellations were systematized by a seafaring people, rather than an agricultural civilization. Although primarily agricultural, the Babylonians did trade by sea: but their voyages took them into the Indian Ocean and far enough south to have seen stars that are not described by Aratus.

Instrument of navigation

If not the Babylonians, then who? What we require is a seafaring nation near latitude 36 degrees that prospered around 2000 B.C. The answer, says Roy, is the Minoan civilization of the island of Crete. It was the Minoans, he suggests, who took Babylonian sky lore and turned it into a precise instrument of navigation.

But why was the Minoan sky map so far out of date when it was adopted by Eudoxus? Geologists have the answer. About 1450 B.C., a colossal volcanic eruption blew apart the island of Thera, a Minoan outpost 75 miles north of Crete. The eruption was one of the most violent in the known history of the Earth. The quakes, the ash falls, and the tidal waves devastated Crete, and dealt Minoan civilization a blow from which it never recovered.

Perhaps Minoan sailors were stranded in Egypt at the time of the eruption. Perhaps a Minoan navigational star globe made its way into the archives of Egyptian priests, where it was discovered by Eudoxus when he visited Egypt 1000 years later.

If Roy is right, Orion, Taurus, Sagittarius, and the other familiar constellations were invented on the island of Crete by Minoan seafarers, and frozen forever in time by a geological caprice of the Earth.