Originally published 23 June 1986

Ever since bioengineers learned how to tinker with DNA and turn out tailor-made living organisms we have been hearing jokes about “designer genes.”

Well, according to a [June 1986] report in Scientific American, it’s no longer a joke.

A small biotech outfit in Houston called NovaGene claims to have inserted the name of the company into the genetic code of its live product — as surely as Gloria Vanderbilt and Calvin Kline stitch their logo onto the seat of your pants.

NovaGene’s product is a genetically-engineered live-virus vaccine designed to counter a disease of cattle called infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. As an extra twist, the company inserts the name “NovaGene” into the viral DNA. Whenever the virus replicates, the company’s logo is also reproduced. The “NovaGene” logo has become part of the fabric of life on Earth, although the branded virus has not yet been approved for field testing by the government.

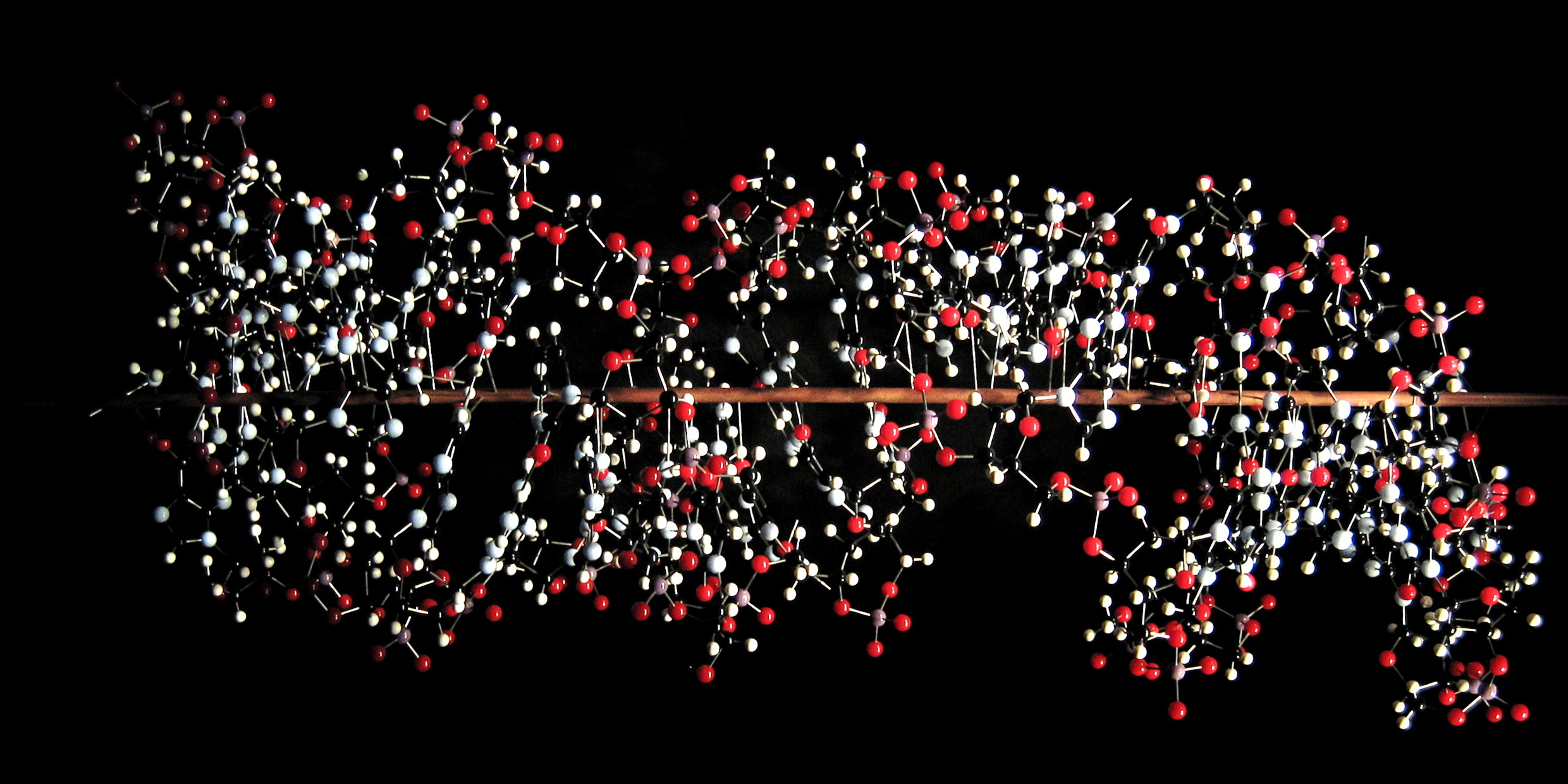

The technique for branding a live product was invented by Malon Kit, a physician and bioengineer who is also the president of NovaGene. Here is how he does it: The genetic code of a living organism is stored on a long twisted molecule known as DNA. The code is chemical, and it contains the information that enables the organism to build molecules called amino acids in an appropriate sequence. The amino acids are the subunits of the proteins. There are 20 or so amino acids, and in a chemical shorthand each of them can be designated by a letter.

Using standard techniques, Kit spliced into the viral DNA the codes for a sequence of amino acids for which the letter symbols spell “NovaGene.” The letter N is the symbol for the amino acid asparagine, and asparagine is the first coded amino acid in the sequence. It is followed by glutamine (Q — there is no amino acid designated by O) — valine (V), alanine (A), glycine (G), glutamic acid (E), asparagine (N), and glutamic acid (E).

Keeping logo harmless

Although the “NovaGene” logo will be copied every time the virus replicates, it is important that the “NovaGene” gene not be expressed; that is, that the virus does not try to build an amino acid sequence based on the “NovaGene” code. To forestall this possibility, Kit inserts the company logo into the DNA far away from the start codes, those DNA segments that turn on protein production. And even if the logo code were somehow expressed, the resulting chain of amino acids would presumably be too small to function as a biologically active molecule.

If necessary, the logo can be read by isolating the virus from tissue and exposing it to a substance that binds to the DNA molecule at the “NovaGene” code.

Dave Banker, vice-president of finance and business at NovaGene, expressed satisfaction that his small company that was the first to put a brand name into a living product, beating out the big pharmaceutical houses. NovaGene is now looking for venture capital, and a news-catching breakthrough like branding will certainly help.

I also spoke with Malon Kit, the creator of DNA branding. He wanted to talk about the broader technical achievements of his company, but I stuck with branding; after all, putting a brand name into the codes of life seems to me a historic step in the expression of the American business dream.

Benefits of branding

Asked to explain the value of DNA branding, Kit mentioned three things: First, he said, branding protects the company against liability claims. For example, if something happens to a cow after vaccination, the farmer will tend to blame the vaccine. The company can determine if the vaccine was an authorized version of the product.

Second, branding provides government regulators with a handle for maintaining and verifying the safety and efficiency of products they have approved.

Third, branding will help prevent bootlegging of a live product by other companies. According to Kit, this can be a problem for companies hoping to recover research and development costs for a product that will happily replicate in someone else’s laboratory.

If NovaGene has branded a virus, then brand-name organisms have made their appearance in the tree of life. There is no reason, I suppose, why DNA branding cannot be applied to any living organism. An engineered virus is obviously the place to start, but special-purpose bacteria will not be far behind.

Even for humans, the difference between designer jeans and designer genes could be only a matter of time. Perhaps someday you can have your own DNA branded with the logo of your choice, like a bumper sticker on your car. Then, cell by cell, your message will be replicated, down through the generations.