Originally published 9 December 1996

“In the city of Pisa, a little boy was born with stars in his eyes. His parents named him Galileo.”

So begins the story of Galileo Galilei in Peter Sis’ new children’s picture book, Starry Messenger.

The words are accompanied by a wonderful drawing of dozens of swaddled infants, packed together like eggs in a crate, all in full voice, the offspring of carpenters, cobblers, soldiers, cheese-makers, serving maids, executioners — each child’s parent identified by a picture on its blanket. Among the bawling infants is a child whose blanket is the color of the night and covered with stars.

It is astonishing how much of Galileo’s life and work Sis has managed to condense into 15 double-page spreads, most of which are given over to drawings that are witty and whimsical even as they evoke the style and substance of Galileo’s time. There are marginal quotes in script, as if in the hand of Galileo himself. Sis’ own text is concise, a few dozen words on each double page:

“His fame grew…and the celebrations became extravaganzas. But now the Church began to worry. Galileo had become too popular. By upholding the idea that the Earth was not the center of the universe, he had gone against the Bible and everything the ancient philosophers had taught.”

The sophisticated illustrations and marginal glosses of this book will more likely appeal to adults than to children. Still, so few children’s books take science as a subject that it is a joy when one comes along, especially one as handsomely illustrated as this.

And, when nearly half of Americans believe that the world is less than 10,000 years old, as described in the Bible, the story of Galileo bears repeating.

“I think that in discussions of physical problems [nature], we ought to begin not from the authority of scriptural passages but from sense-experiences and necessary demonstrations,” Galileo wrote, and his words are curled into the shape of an eye in a margin of the book.

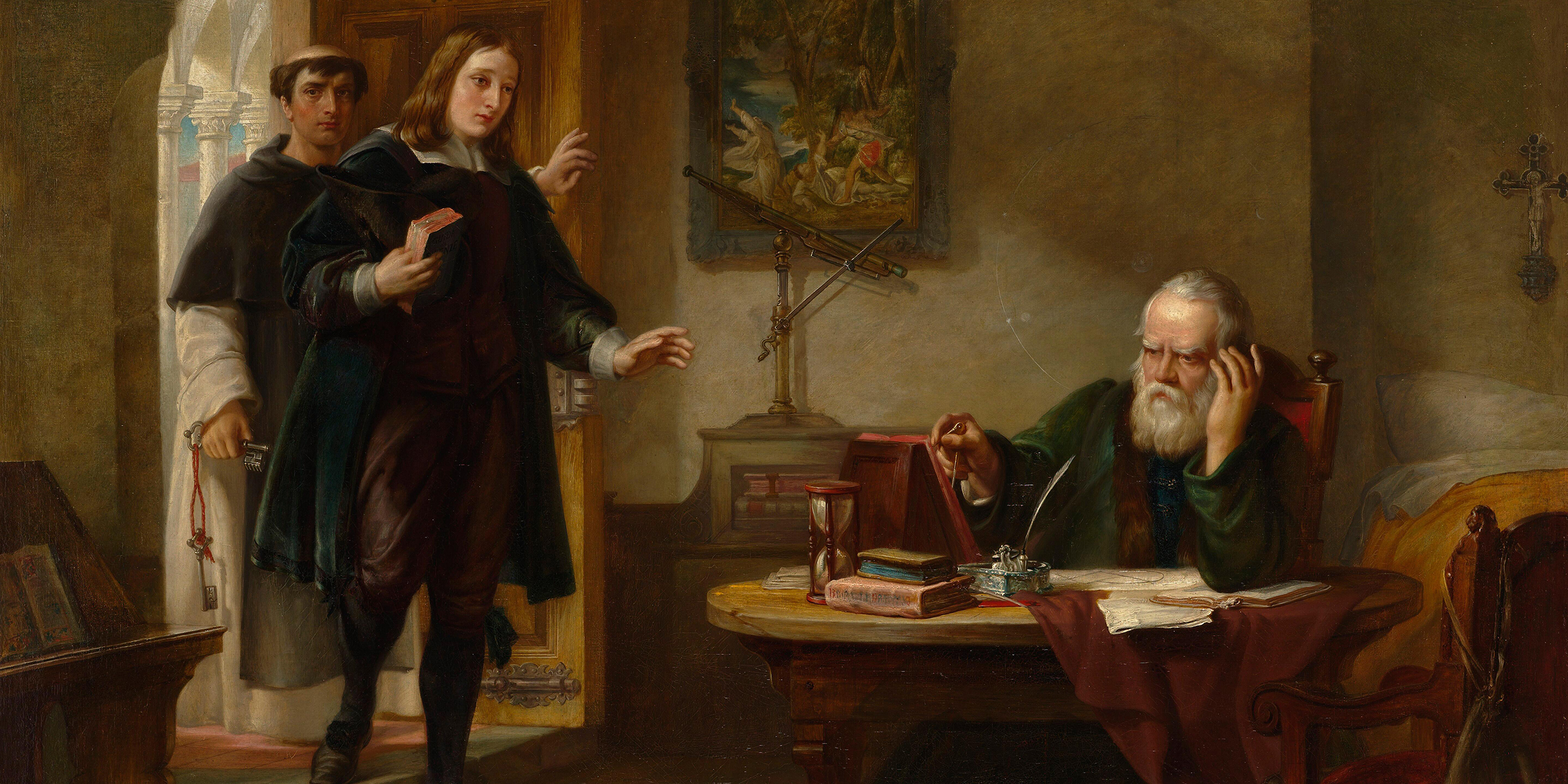

Sis’ marvelous illustrations show Galileo in the dungeon of the Inquisition, on trial before the assembled princes of the Church, and under house arrest in Florence. The images are powerfully rhetorical, rich in symbolism, both fanciful and true. They have a fairy tale quality that will appeal to the child in all of us.

On the last page, we are reminded that it was not until Oct. 31, 1992 that the Roman Catholic Church at last officially pardoned Galileo for his crime. His “crime,” of course, was to believe that the Earth moves about the sun, that the moon has mountains, that the sun has spots, that Jupiter has satellites — things that even fundamentalist Christians now concede to be true.

Unfortunately, other equally well-grounded scientific truths, such as the evolution of life by common descent and the antiquity of the Earth, continue to be dismissed by many Christians because of an apparent contradiction with Genesis. Thus the media fuss in late October when Pope John Paul II decreed that “evolution is more than a hypothesis.”

More to the point, the pope addressed the question of evolution in words startlingly reminiscent of Galileo: “The sciences of observation describe and measure with ever greater precision the multiple manifestations of life…while theology extracts…the final meaning according to the Creator’s designs.”

Alas, the pope’s opinion probably has less influence on the beliefs of Americans than, say, the Institute for Creation Research in California, a creationist organization that affects scientific credentials and whose pseudoscientific propaganda probably reaches into more homes than the pope’s voice ever will.

Henry Morris, president emeritus of the institute, is quoted in Time magazine as saying: “There is no scientific evidence for evolution. All real solid evidence supports creation.” This cockamamie opinion has been expressed so often, from so many pulpits, in so many radio and television exhortations, and on so many web sites that it is taken seriously by millions of people.

Which is why it is good to see a talented and thoughtful artist like Peter Sis give such vivid expression to Galileo’s affirmation of the excellence of the human mind as an instrument for discerning the truth of the world. Sis quotes Galileo: “I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with senses, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.”

The penultimate drawing in Sis’ book shows Galileo under house arrest in Florence. He stands in a moonlit garden, surrounded by the wonders of God’s cosmos, with mathematical demonstrations described on the bright interior walls of his prison. Beyond the walls, in the ostensibly unimprisoned world, all is darkness. The lesson is clear: It is our senses, reason, and intellect that make us free.

It is astonishing that 350 years after the trial and condemnation of Galileo we are still fighting the battle of senses, reason, and intellect against the literal interpretation of an ancient Mideastern creation myth. Sis’ Starry Messenger is a welcome restatement of a much needed message.