Originally published 2 March 1998

An e‑mail query from a young acquaintance: “One of my favorite songs in all of explored space is ‘Jupiter Crash’ by The Cure. One of the lines is ‘…meanwhile millions of miles away in space/ the incoming comet brushes Jupiter’s face…’ Well, I just read an interview in which Robert Smith alludes to the Jupiter crash as if it were an actual event. I had thought that it was just something he had made up. So if it is real, what exactly is a Jupiter crash?”

I had a pretty good idea what might be the “Jupiter crash.” But first I had to make a trip to the Internet to learn about The Cure, Robert Smith, and the lyrics to his song.

The Cure is a British male rock band, formed in 1978 and still going strong. Robert Smith, who writes and sings the songs, was a founder of the group, which has seen a lot of faces come and go. He remains the band’s central figure.

The song “Jupiter Crash,” copyrighted 1996, is about a nighttime encounter with a woman on the sand by the sea, which the lyricist likens to a comet crash in space — the irresistible attraction, the violent splash into Jupiter’s gassy sphere, the disappearance without a trace. “Is this how it feels?” asks the lyricist. “Is this how a star falls?”

No doubt about it, Robert Smith is referring metaphorically to the great comet crash of 1994, the most violent event ever witnessed in the solar system.

The comet was Shoemaker-Levy 9, discovered on March 25, 1993, by the prolific husband-and-wife comet-finding team of Gene and Carolyn Shoemaker working with ace comet-hunter David Levy, on photographic plates made with an 18-inch telescope on Palomar Mountain.

The comet, when it was discovered, had recently undergone a close encounter with Jupiter. Astonishingly, the gravity of the giant planet had ripped the comet into a string of 21 pieces, strung out in space like beads on a string. Nothing like it had ever been seen before.

The comet was still caught in Jupiter’s gravity. Astronomers quickly calculated that after a short excursion away from Jupiter, it would cycle back and crash into the planet in July 1994.

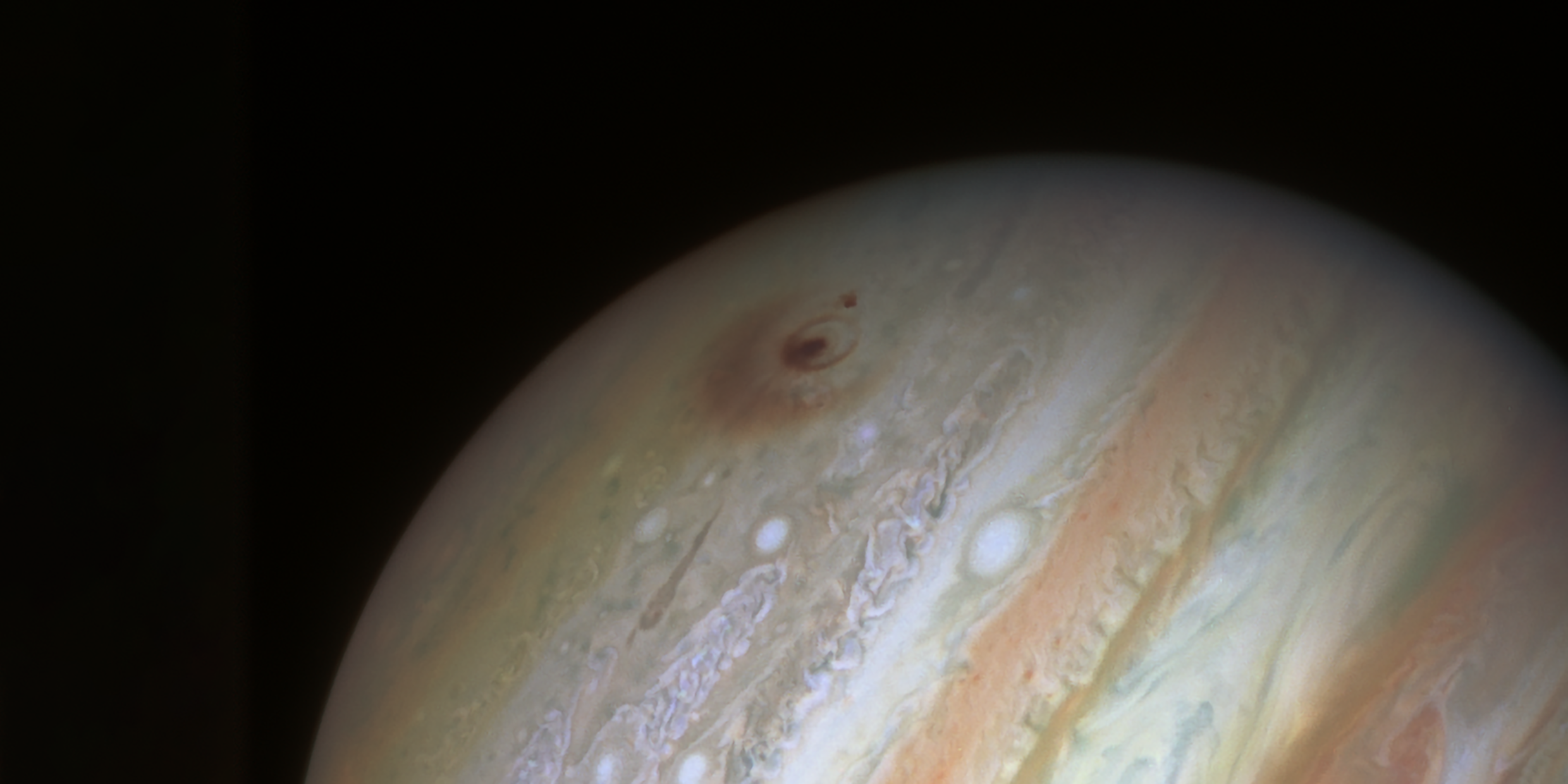

Few astronomical events have caused so much anticipation and excitement among astronomers. The successive impacts of the chunks of Shoemaker-Levy 9, spread out over a week, were observed by countless telescopes on Earth and by the Hubble Space Telescope.

The scars on Jupiter’s face remained visible for almost a year.

David Levy, co-discoverer of the comet, has recently published a little book, called More Things in Heaven and Earth, that compares the ways poets and astronomers read the night sky. He does not include rock lyrics, but poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins, John Keats, and Robert Frost figure prominently.

One of the loveliest astronomical images in Levy’s book was penned by Hopkins in September 1864, less than a month after the pre-dawn appearance of Comet Tempel. The poet compares himself to “a slip of comet,/ Scarce worth discovery.” A comet comes out of space, brightens as it approaches the sun, then goes “out into the cavernous dark”:

So I go out: my little sweet is done: I have drawn heat from this contagious sun: To not ungentle death now forth I run.

A personal favorite Hopkins poem, omitted by Levy, begins:

Look at the stars! Look, look up at the skies! O look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air! The bright boroughs, the quivering citadels there! The dim woods quick with diamond wells; the elf-eyes!

Another favorite astronomical image are these lines spoken by the Earth in Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, which beautifully describes something the poet has seen only in his mind’s eye — the Earth’s shadow, a long cone of darkness reaching out into space far past the moon:

I spin beneath my pyramid of night Which points into the heavens, dreaming delight, Murmuring victorious joy in my enchanted sleep; As a youth lulled by love-dreams faintly sighing, Under the shadow of his beauty lying, Which round his rest a watch of light and warmth doth keep.

I have often thought of Shelley’s image as I watched the moon move into the Earth’s shadow during a lunar eclipse, especially during the wonderful April 1996 eclipse that coincided with the appearance of Comet Hyakutake.

David Levy has discovered or co-discovered more than 20 comets, including the one that crashed into Jupiter. Through his discoveries and writings he has made himself one of the world’s best-known astronomers. However, he has never taken an academic course in astronomy; his degrees are in English literature, which helps explain the poetic sensitivity that he brings to the telescope — and to his writings about the spectacular demise of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9.

“Yeah, that was it. That was the Jupiter crash. Drawn too close and gone in a flash,” sings Robert Smith about his nocturnal encounter on the sand. These sorts of lyrics are not likely to touch the heart or mind of an old fogey like me, but it’s good to know that poets of the rock generation have not lost their contact with the sky.