Originally published 28 February 1994

Physicist Albert Wattenberg was poking about in the Chicago branch of the National Archives recently. He was looking for artifacts used by Enrico Fermi and his team of nuclear physicists in achieving the first self-sustaining nuclear reaction in a squash court under the University of Chicago’s football stadium in December 1942.

Wattenberg had been on Fermi’s team. Now, more than 50 years later, he reached into a box and picked up an 8‑inch metal rod. Its heft surprised him. “There’s only one metal that heavy,” says Wattenberg. “It was obviously uranium.”

Radioactive uranium.

Wattenberg’s discovery led to an examination of other documents and artifacts in the archives. Hundreds of laboratory notebooks and papers dating from the early days of nuclear research turned out to be contaminated with radioactivity.

The early 1940s were a careless time in nuclear physics. Scientists were heady with the excitement of discovery. A war was on; a nuclear bomb could shorten the war and save American lives. The dangers of radiation were not as well understood as they are today. Safety sometimes went by the board.

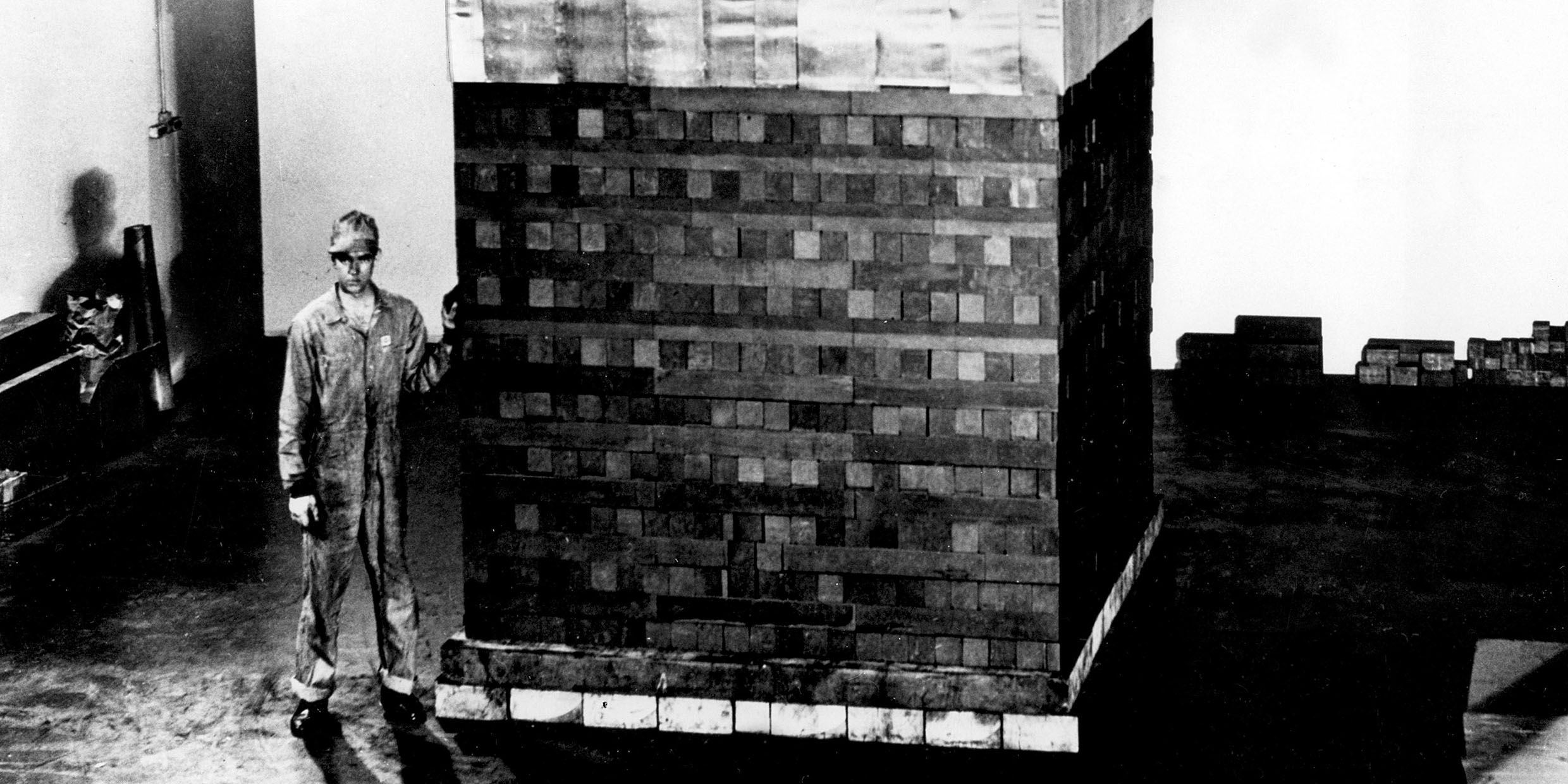

In the squash court under the stadium, Fermi pushed his team to assemble the first nuclear reactor, a room-sized pile of graphite bricks interspersed with chunks of uranium and uranium oxide. If all went well, a chain reaction of disintegrating uranium atoms, triggered by neutrons, would produce a new form of energy.

Graphite dust blackened walls, floors, faces, notebooks. It was dirty work, as different as one can imagine from the white-coated, dust-free environments of modern nuclear facilities.

At last the moment came to allow the reactor to go “critical.” Neutron-absorbing cadmium rods were slowly removed from the pile, under Fermi’s direction. There was concern that the reaction might get out of control, that the pile might melt down. A “suicide squad” of three young physicists stood by with jugs of neutron-absorbing cadmium-sulfate solution to douse the reactor.

All of this in the middle of a crowded city.

The self-sustaining reaction was achieved. For four-and-a-half minutes, Fermi let neutrons multiply. Left uncontrolled, a runaway reaction would have killed everyone in the room and caused a mini-Chernobyl.

But before that happened, control rods were re-inserted and the chain reaction halted. The physicists shared a celebratory bottle of Chianti. The crowd departed. Fermi stayed behind with Leo Szilard, the physicist who had first imagined that a nuclear chain reaction was possible. Szilard shook Fermi’s hand and worried that the day would go down as a black day in the history of mankind.

History’s judgment of what was accomplished that day is mixed. But that the day was literally black is beyond dispute. The dust of graphite was everywhere, apparently contaminated with radioactivity. Even today, radioactive material lingers on things the physicists touched, boxes and boxes of historical documents, documenting in an unexpected way the casual birth of the nuclear age.

In those early days, many researchers and workers were accidentally contaminated. Research on the physiological effects of radiation was a medical necessity. Some medical experiments were entirely proper and useful. Others raise troubling questions of ethical responsibility:

In 1945 – 47, eighteen supposedly terminally-ill hospital patients were injected with high doses of plutonium to learn whether the body absorbed it, without informed consent of the patients or their families.

About the same time, six hospital patients were injected with uranium salts to determine the dose that produced injury to the kidneys. No informed consent.

More than a hundred prison inmates had testicles exposed to x‑rays to determine the effect of radiation on sperm production. Eleven comatose brain cancer patients were injected with uranium to learn whether it is absorbed by brain tumors.

In other medical experiments, small and probably harmless levels of radiation were used as “tracers” on populations that included infants, retarded children, blacks and women, often without informed consent.

These revelations compound an already well-known record of experiments involving humans and radioactivity in the 1940s and ’50s, such as the exposure of soldiers to detonations of nuclear weapons.

In retrospect, it is easy to make judgments about the appropriateness or inappropriateness of these experiments. At the time, the ethical issues were less clear, national security seemed paramount, and safety rules were lax by present standards (Can you imagine an experimental reactor in the heart of Chicago today?). An exhilarating buzz of discovery was in the air as scientists rushed to wrest from nature the secrets of nuclear transmutation.

In their zeal to discover, the scientists created a mess of radioactive pollution that dirtied their own lives and the lives of Americans around them, including the helpless, the incarcerated, and the terminally ill. In their well-meaning enthusiasm, they left contaminated fingerprints on the pages of history.