Originally published 10 June 1985

It has been 55 years since Clyde Tombaugh, a young assistant at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, found a smudge of light on a photographic plate that moved from night to night. That smudge was Pluto, the ninth and most mysterious member of the sun’s family.

The planet’s name was suggested by an 11-year-old English girl named Venetia Burney. The god of the dusky underworld seemed an appropriate namesake for a planet that moved on the shadowy fringe of the solar system. From the vantage of Pluto, the sun appears no bigger than Jupiter in our own night sky, although it provides considerably more light.

Pluto remains a mystery. Astronomers debate whether it should be considered a planet at all. If so, it is certainly the smallest of the planets, smaller even than tiny Mercury. It has an unusual orbit for a planet, eccentric and tipped at an unlikely angle to the plane of the solar system. The great eccentricity of Pluto’s orbit sometimes brings it closer to the sun than Neptune, as is presently the case. Pluto takes 248 years to revolve around the sun.

Some astronomers would prefer to call Pluto a large asteroid. Others have wondered if it might not be the supersize nucleus of a comet. Still another widely held notion is that Pluto is a moon of Neptune that was flung into an independent orbit by a cataclysmic encounter with another celestial object.

A moving bump on a blur

Until 1978, astronomers had only vague ideas of the size and mass of the distant traveler. In that year, James Christy of the Naval Observatory discovered that Pluto has a moon. That moon has been a revealer of secrets, and the pace of those revelations is about to step up.

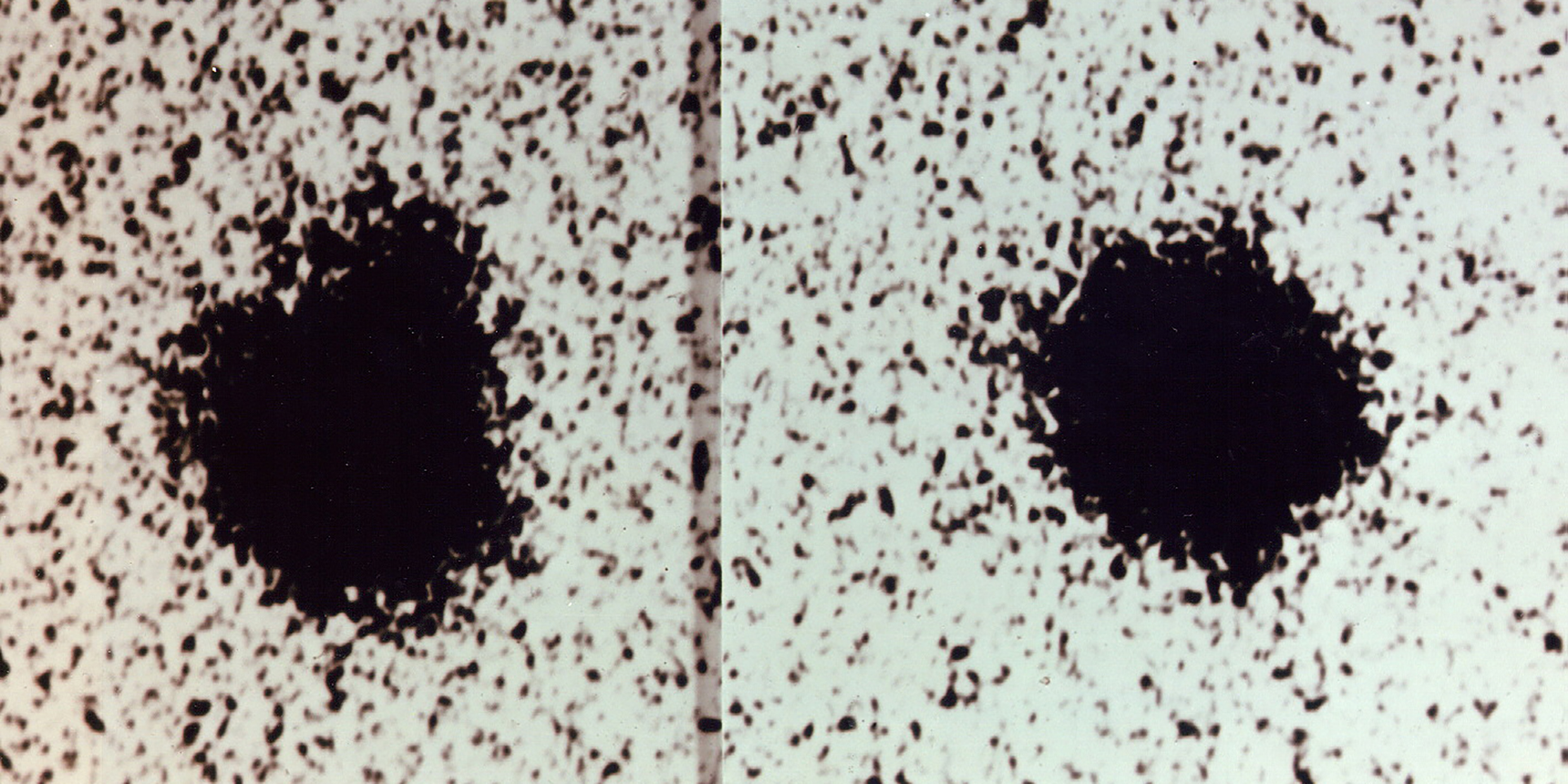

Pluto’s moon appeared on Christy’s photographic plates only as a moving bump on the circular blur that is the best image we can get of the planet. The bump rotated about the blur every six days; that is the time it takes the planet to rotate on its own axis, as deduced from slight periodic variations in the brightness. Pluto and its moon appear locked in a synchronous dance, always presenting the same face to one another.

The discovery of the moon made it possible for astronomers to use gravitational theory to calculate the planet’s mass as only one quarter that of our moon. The spectrum of sunlight Pluto reflects reveals the presence of frozen methane. From that reflectivity of methane and the brightness of the planet, it was possible to estimate Pluto’s size: a little more than 2000 miles in diameter, roughly the size of Earth’s moon. The average density of the planet is therefore somewhat less than water. Pluto is certainly not a rocky planet like Earth.

Christy names the newly discovered moon Charon, after the god who carried souls to Pluto’s nether realm. But the International Astronomical Union has refrained from making the name official until the satellite’s orbit is determined with certainty. For seven years Charon has been in a kind of limbo, officially known only as 1978 P 1. That is about to change.

Season of mutual eclipses

The plane of Charon’s motion about Pluto is tipped at a high angle to the plane of the solar system. As seen from Earth, the moon appears to pass above and below the face of the planet as it orbits around it. But once every 124 years, for a span of half-a-dozen years, the orientation of the orbits is such that Charon moves in front of and behind Pluto when viewed from Earth. One of those seasons of mutual eclipses has just begun.

As Charon moves across Pluto, or behind the planet, the combined light of the two is diminished in a characteristic way. The first grazing contact of Charon and Pluto was noted January 16 by Edward Tedesco and Bonnie Buratti of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, using the 60-inch telescope on Mount Palomar. The blur of light that was Pluto and Charon noticeably dimmed. The partial eclipses have been confirmed by other investigators.

By carefully monitoring Pluto and its moon as they periodically obstruct each other’s light, it will be possible to refine their orbital parameters and to obtain better estimates of their sizes and masses. It might even be possible to map surface features of differing intrinsic brightness on the side of Pluto that faces its satellite. Secret’s of the planet’s composition and origin may be revealed.

For the rest of this decade, enigmatic Pluto and its faint companion will be closely watched. The grazing eclipses of Pluto and Charon already have placed the existence of the moon beyond doubt and refined its calculated orbit. It now seems likely that Charon’s existence will be officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union by year’s end. And the bump on the blur will at last take full possession of its name.

Of course, in the decades since this essay was first published, much has been discovered about Pluto and its moon Charon. Most significantly as a result of the close encounter by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2015. The next series of eclipses of Pluto and Charon, as seen from the Earth, will begin in 2103. ‑Ed.