Originally published 11 July 1988

In the summer of 1868, the British Association for the Advancement of Science held its annual meeting in the town of Norwich, 90 miles northeast of London. At that meeting, Thomas Henry Huxley, one of the greatest natural historians of his day and a champion of Darwin’s new theory of evolution, delivered a talk entitled On a Piece of Chalk. His audience was the ordinary workingmen of the town.

Huxley’s subject was engagingly simple — and familiar. Some of the carpenters in the audience may have carried a piece of Norwich chalk in their pockets. The town is built upon chalk, the same extensive beds of soft, white rock that give England its poetic name — Albion.

From a piece of Norwich chalk Huxley extracted a most astonishing story, of a vast saltwater sea that once lay upon Britain, and of the microscopic creatures that lived in the sea in prodigious numbers. In their dying, these tiny animals contributed their calcareous skeletons to bottom sediments that were ultimately compacted into chalk. The skeletons, of a wonderful geometric complexity, are often beautifully preserved.

Eleven years before, the British Admiralty had commissioned Huxley’s friend, a certain Captain Dayman, to sound the floor of the Atlantic Ocean along the route of the proposed Atlantic telegraph cable. Dayman sailed from Valentia, Ireland, to Trinity Bay in Newfoundland, measuring the depth of the sea and retrieving samples of mud from the ocean bottom. These specimens of deep-sea sediments were submitted to Huxley for examination.

Reasonable assumptions

Huxley assured his Norwich audience that the sediments brought up from the floor of the present ocean contain exactly the same sorts of microscopic organisms that are preserved in the Norwich chalk. Where you see the same effect, he said, it is reasonable to assume the same cause. If the fossils in the Norwich chalk resemble in every respect the creatures found in the muddy depths of present ocean — and nowhere else in the world — then it is reasonable to assume that the chalk was once deep-sea bottom sediments.

The chalk beds at Norwich are hundreds of feet thick. I think you will agree,” Huxley told his audience, “that it must have taken some time for the skeletons of animalcules of a hundredth of an inch in diameter to heap up such a mass as that.”

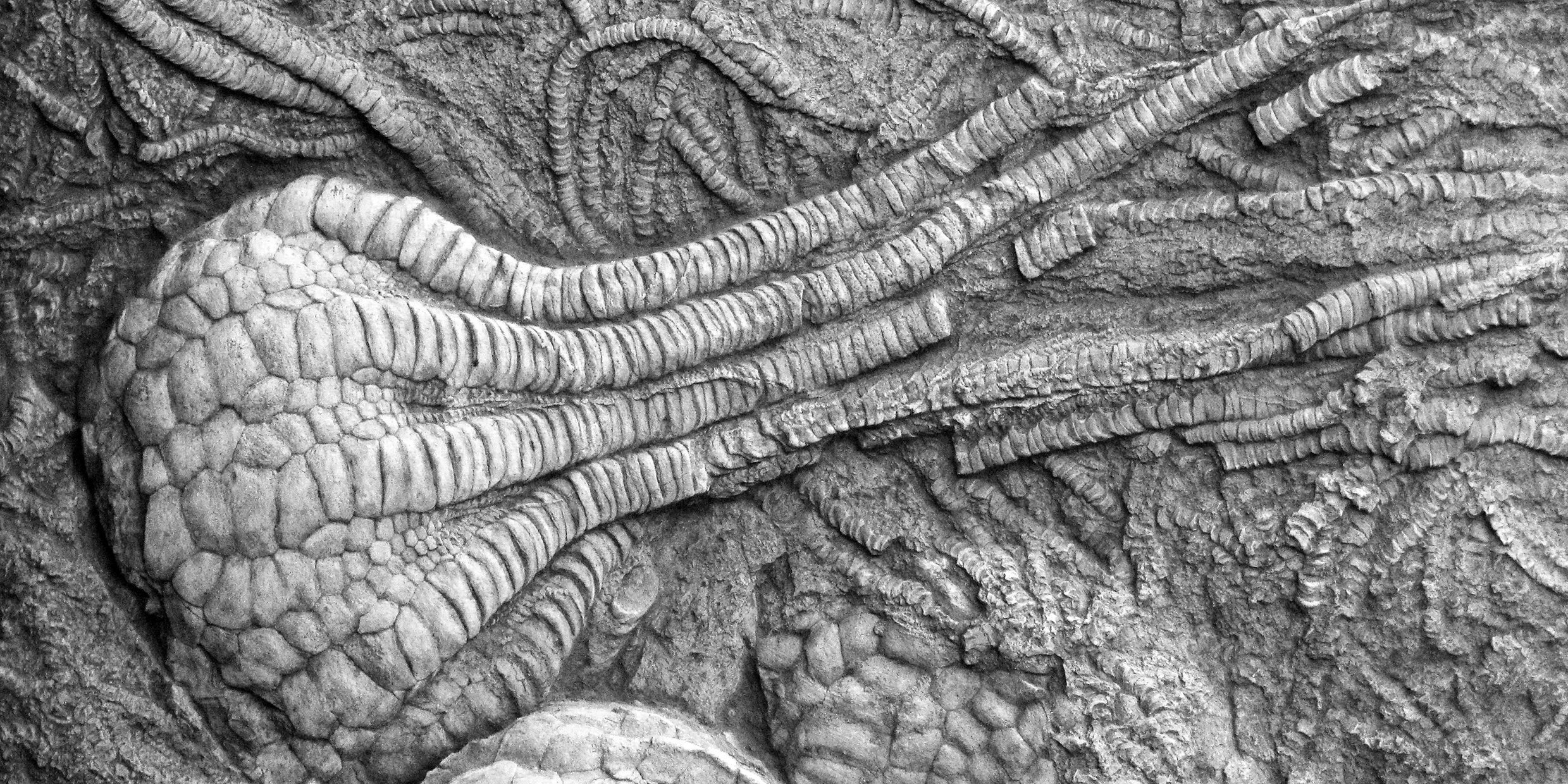

How long? Embedded within the chalk are the fossils of higher animals — corals, brachiopods, sea urchins, and starfishes, altogether more than 3,000 distinct species of aquatic animals — animals that are today found only in the salt sea. Among these fossils there are some curious combinations — for example, a coral-covered shellfish affixed to a sea urchin. Here was a hint to the age of the chalk sea, and Huxley unraveled the story.

The sea urchin lived from youth to age on the floor of the sea, then died and lost its spines, which were carried away. The shellfish adhered to the bared shell, and grew and perished in its turn. Finally, coral-building organisms covered both shellfish and urchin, lived out their lives and expired. And all of this unfolded before slowly accumulating sediments encased these creatures in an inch or two of chalky mud. It was easy for Huxley to deduce that a minimum of tens of thousands of years were required for the deposition of chalk beds hundreds of feet thick.

Giddy transformations

But Huxley’s story of the great depths of time was not yet complete. Where the River Yare flows through Norwich it cuts down through sandy clays to expose the chalk. Since the clays lie above the chalk they must have been deposited at a later time. Between the clay and the chalk there is a layer of vegetative matter, including the fossilized stumps of trees standing as they grew — fir trees with their cones and hazel bushes with their nuts. Clearly the chalk must have been uplifted from the floor of the sea before forests could grow on it.

And a greater surprise! Among the bolls of the trees are the fossilized bones of elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, and other wild beasts that roamed the ancient forest. And above the forest beds, interspersed within clay of a marine origin, are the fossils of walruses and other cold-water sea creatures now found only in the icy waters of the north.

Sea, land, sea, and land again. Spectacular changes in climate. What forces caused such giddy transformations? Huxley did not know and readily confessed his ignorance. But he knew that the evidence of the Norwich rocks “compels you to believe that the earth, from the time of the chalk to the present day, has been the theater of a series of changes as vast in their amount as they were slow in their progress.”

How astonished must have been the members of the Workingmen’s Association of Norwich to hear of this dramatic extension of the history of their town.

Huxley’s lecture On a Piece of Chalk has come down to us as a little classic of scientific exposition, as engaging and informative today as in 1868. It was delivered only a few years after the introduction of Darwin’s theory, at a time when the evolutionary interpretation of the Earth’s past was highly controversial. Huxley did not talk down to his audience. Nor did he grind any theological axes. He simply directed the attention of his audience to the rocks, and let the rocks speak for themselves.

From his piece of chalk Huxley extracted an epic tale of evolution that any teacher who has ever held a piece of chalk might envy.