Originally published 27 August 2006

Last week [in 2006] our part of southeastern Massachusetts was sprayed from the air with insecticide. The target: mosquitoes that carry the virus for Eastern equine encephalitis, an often fatal disease that has already claimed several victims. Not everyone is happy with the spraying, but no one asked our opinion. Will the spraying control human infection? Who knows? But when you consider all the nasty pathogens that would love to bring us down, the fact that we stand at all is a bit of a miracle.

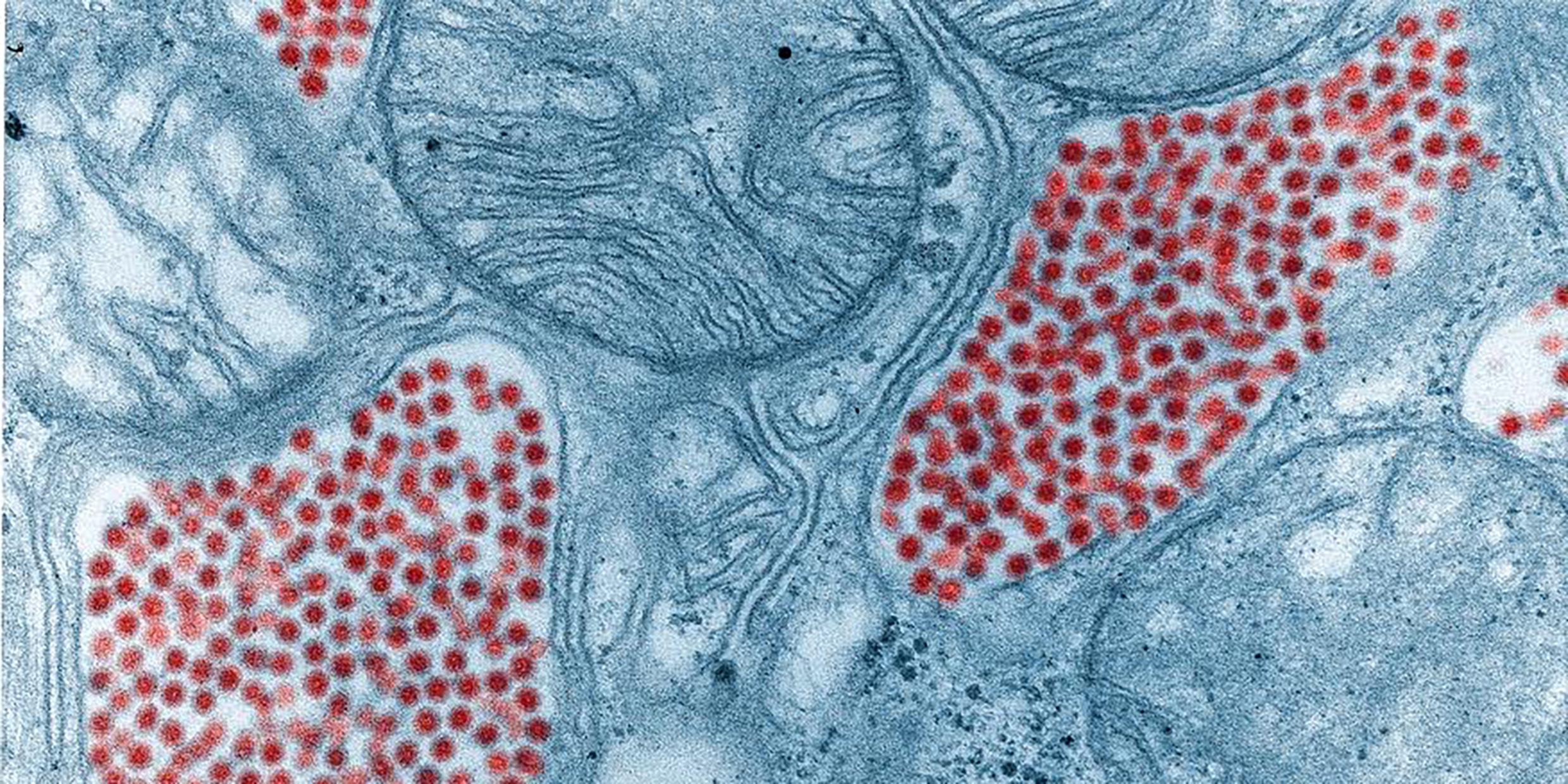

The body is a society of cells. The integrity of the society is under permanent attack by viruses and bacteria capable of causing disease or death. We live our lives in a sea of pernicious microbes.

The body’s first line of defense is the outer walls and moats: the skin, with its impregnable barrier of keratin, and the mucus membranes. Other exterior membranes are flushed with fluids: saliva, tears, and nasal secretions. The skin and the lower intestinal tract harbor populations of benign bacteria that do battle for the body the way pacified tribes on the marches fought for the Roman Empire.

Despite all of these defenses, viruses and microbes penetrate the body. Sometimes they overwhelm the outer defenses by force of sheer numbers. Or they slip in quietly by an unguarded gate. They are masters of deceit and disguise.

Once the enemy has penetrated the outer membranes, more sophisticated defense systems swing into action. The presence of an alien microorganism triggers chemical alarms that cause white blood cells to move to the site of the intrusion. The white blood cells do their best to engulf the enemy the way an amoeba engulfs its prey.

If the foe is a virus, the infected cells of the body release small proteins called interferon, like cries of warning. Interferon rouses the surrounding cells and stimulates their resistance to infection by the virus.

Most effective of all the body’s defenses are the lymphocytes, the agents of the immune response. Lymphocytes are small, round, non-dividing cells that are always on the alert. At any time there are as many as 2 trillion lymphocytes patrolling the human body. The huge number is crucial: Lymphocytes are very specific about what intruders they can recognize. Each lymphocyte is trained by evolution to respond to a particular alien.

Recognition of a foreign body causes lymphocytes to become active and start dividing. The offspring cells produce huge numbers of antibodies. The antibodies go to work attacking the invader. The presence of two particular antibodies in the blood is a diagnostic for Lyme disease.

Many alien viruses and microorganisms are harmless. Some are deadly. The body is protected by a stupendous array of traps, triggers, walls, moats, and chemical alarms. Some of the body’s cells act as patrols, sentries, infantry, and artillery to defend the integrity of the larger society. The defense system never rests. And all of this goes on without our awareness — unless and until something goes wrong.

But my cell wars story is not over yet. When all the unconscious defenses fail, the human body has an ultimate weapon: the brain, a tangle of cells that evolved for something rather different than defense against disease. We are the only creature to supplement its immune system with the products of conscious invention. Calls them laser-guided smart bombs, if you will, but thank your lucky stars for vaccines and antibiotics.

And now, having used all of these military images, I am a little abashed. It seems that I have painted a picture of the body as an unceasing battleground, every cell looking after itself. Nothing could be further from the truth.

If there is a lesson to be learned from the defense system of the human body, it is that life is characterized mainly by cooperation. The great thrust of evolution has always been toward “getting along.” A cellular society as complex as the human body could not exist for even a minute unless the common good took precedence over individual concerns.