Originally published 24 June 1985

In geology, before the 1960s, we were taught the Earth was “as solid as a rock.” And we were told the surface of the Earth had always looked more or less the way it looks today, the same continents, the same ocean basins. Oh yes, there had been changes on the surface, crinklings and foldings that lifted mountains or cracked the crust, vertical movements mostly, like the wrinkles on the skin of an orange.

Today, every school child knows this isn’t so. The “drift of continents” is now a commonplace, and a new theory — the theory of plate tectonics — describes the changes that affect the crust of the planet.

In the new geology, the movements that shape the crust are not vertical, but horizontal. The Earth is more like an egg than a billiard ball. The rigid crust is thin, as thin relatively speaking as the shell of an egg, and the crust floats on mantle rocks that are hot and soft. The crust is cracked into sheets called plates, and the plates slip and slide across the face of the Earth colliding and diverging.

The theory of moving plates has had impressive success in explaining the major features of the Earth’s surface. Mountains are located where plates collide, ocean trenches where one plate slips beneath another, and sea floor rift valleys where plates diverge. Earthquakes and volcanoes are overwhelmingly confined to plate boundaries.

CAT scan of earth’s body

But a nagging question remains: What drive the plates? What is the force that drags the continents and sea floors hither and yon, now crunching them together, now pulling them apart?

Most geologists have assumed that the driving force of plate tectonics is convection currents in the hot mantle of the Earth; great loops of rising and sinking plastic rock — hot rock rising, cool rock sinking — moving an inch or so a year, like pudding in a pan on the stove. According to the gospel, it is this turmoil under the crust that breaks and moves the plates.

But all of that was conjecture. Earth’s interior is hidden from direct observation. Now, a technique called seismic tomography is providing crude maps of convection loops.

Seismic tomography does for Earth’s body what the diagnostic technology called CAT scanning does for the human body. CAT stands for “computer-aided tomography.”

In medicine, X‑rays are projected through the body at different angles and recorded, and the degree of absorption of the X‑rays depends upon the density of the organs they pass through. An ordinary X‑ray photograph shows a two-dimensional image. In a CAT scan, the crisscrossing X‑rays are analyzed mathematically by a computer to construct a three-dimensional image that can be displayed on the screen of the computer.

Support for convection theory

In seismic tomography, the source of the waves that pass through the Earth’s body is an earthquake. The waves are recorded at seismic stations across the face of the planet. By recording the shocks of many earthquakes, seismologists can get the same crisscrossing effect employed in a CAT scan.

The velocity of an earthquake wave depends upon the temperature and density of the material it passes through. By mathematically analyzing the arrival times of earthquake waves at many stations from many quakes, it is possible to assemble three-dimensional temperature and density maps of the inside of the Earth. The technique requires a worldwide network of seismographs able to record data in a digital form that can be read by a computer. And the huge bulk of the calculations requires a powerful high-speed computer.

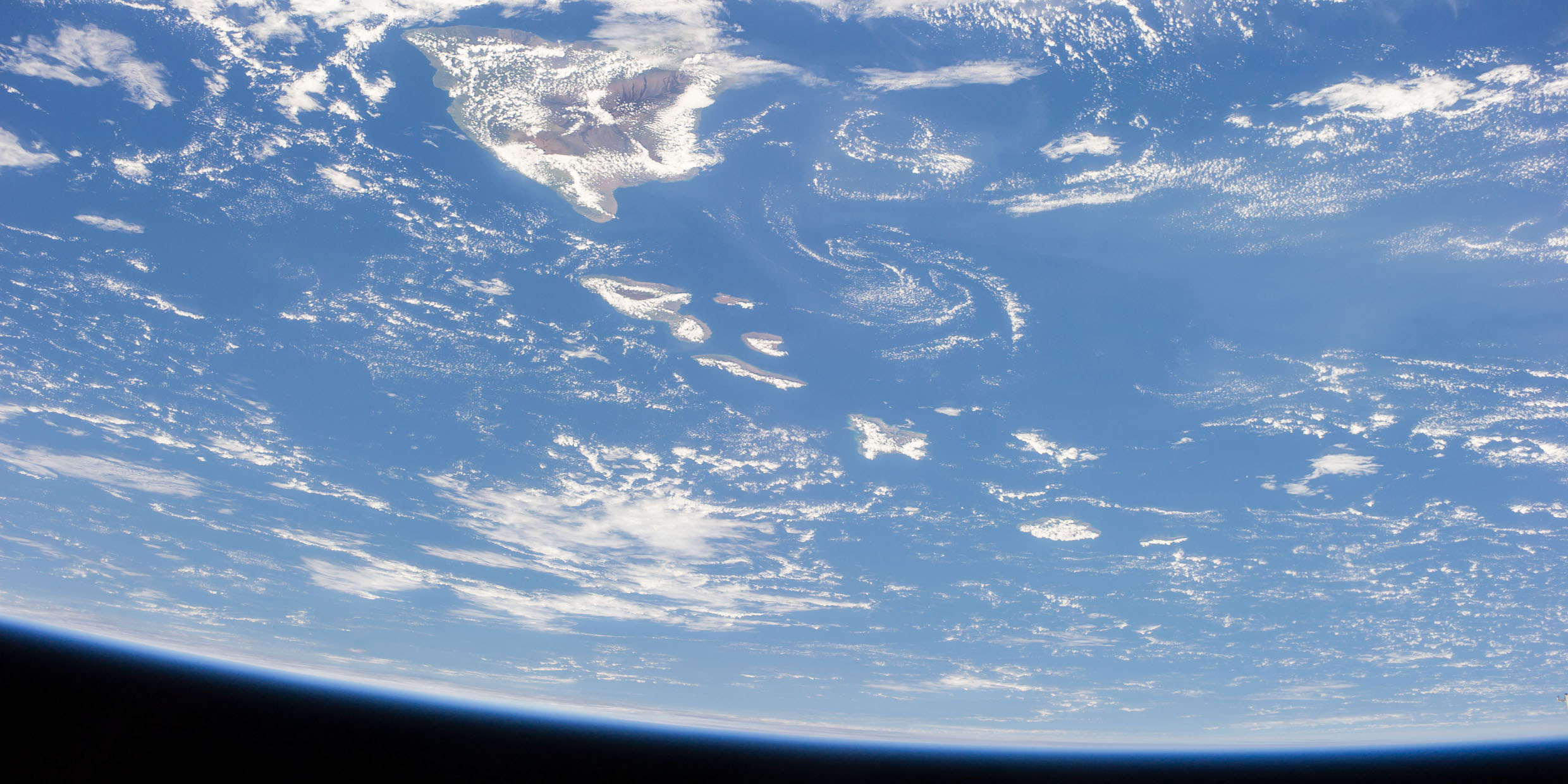

Although the maps so far are rough, they do seem to confirm the belief convection currents drive the plates. There is hot, rising rock close to the surface under places where plates diverge, and under “hot spots” like Hawaii and Iceland. These plumes originate deep in the mantle, but not necessarily directly below the places where they reach the surface. Where plates converge, cold slabs of old crust can be detected far below the surface. Some modest progress has been made mapping the horizontal flow of rock that completes the convection loops.

The key to improving the maps of the Earth’s interior is the emplacement of a wider network of digital seismographic stations. Seismologists from nearly 50 universities and research institutions recently formed a nonprofit corporation with the objective of modernizing and digitalizing seismographic stations, and increasing the number of stations that are distributed across the face of the Earth. With that network they hope to prepare detailed maps of the planet’s interior and of the currents of moving rock that drive the surface plates.